To celebrate Black History Month 2017, NCA is pleased to share the legacy of Mr. Allen Newton Frazier. Like so many African-Americans of his generation, he lived through a radical transition of the Armed Forces, from segregated to integrated. Frazier is also unique because he started his service with the Merchant Marine, in which he proudly served during World War II, but chose the Merchant Marine because he was not permitted in the Navy.

As the post-War military began to downsize, many Americans returned to civilian life, but Frazier simply chose to continue serving: he enlisted in the Marine Corps and was part of the Montford Point Marines. Collectively, the Montford Point Marines received a Congressional Gold Medal in 2012. Frazier was able to share in that belated honor after his service.

Please enjoy NCA intern Maari Weiss’s research into the Veteran legacy of Frazier.

Allen Newton Frazier turned service into a career. As an African-American Marine, he experienced the Armed Forces both before and after integration, and, though he faced some discrimination, he “enjoy[ed]” his work and found it to be “rewarding.” After moving to Washington, DC to live in the Armed Forces Retirement Home in 2004, Frazier wrote a memoir describing both his life and his service.

Frazier was born and raised in Montclair, New Jersey. He grew up in a home in which visitors “were from different or mixed racial backgrounds. At the time [he] thought this was the way the whole world was and how everyone got along so nicely.”

When Frazier was 16 years old, he “went to work in a small defense plant in Belleville, New Jersey.” Before getting this job, he “tried to enlist in the Navy without saying anything to [his] parents.” He thought that he was turned away due to his lack of parental consent, but he later learned that the Navy’s monthly quotas for Black servicemen also played a role. Undeterred, Frazier joined the Merchant Marine, as “[t]hey weren’t particular about who an individual was as far as color was concerned. By 1944 they were taking men as young as sixteen years old.” Frazier remembered that he and many of the other Black people he knew “thought if we went in [to the service,] it would cause society to give the blacks a better chance in life in this land.” When he chose to spend some of his liberty time at home with his family, his father “was anxious to … show [him] off in [his] uniform.”

Frazier was assigned to Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn for basic training, when he was 17 years old. “The training was scheduled to last for about eight weeks, but because of the need for men[, he] was only there for approximately five weeks.” After training, men were assigned to ships individually, and Frazier was sent to the SS Oremar. Before the ship was ready to leave, the Japanese surrendered, ending the war. Frazier celebrated Victory in Japan Day in Times Square, recalling that it “was the wildest time that I can remember in my whole life. …It was wall to wall people. …I thought for once all Americans were the same and were pulling together for one cause.”

Although the war was officially over, the work of the Merchant Marine did not immediately come to an end. In addition to serving aboard the SS Oremar, Frazier signed on to the SS Jonathan Elmer and the MS John Ericsson, bringing “relief supplies…to Poland” and transporting war brides, among other activities. After about a year, “[t]he war economy was winding down and jobs were beginning to get scarce in the Merchant Marine.” Frazier could not find a position on another ship, and he had received “a card from the draft board telling [him] to sign on a ship or report for the draft.” It was at this point that he decided to enlist in the Marines.

In August 1946, Frazier was sent to Montford Point Camp, which was located in Camp LeJeune in North Carolin

Frazier’s mother, taken circa 1915.

a. He recalled that “Camp LeJeune and the South were a whole new way of life for me. […] I remember my parents telling me not to get out of line with any of the white southerners. The military was segregated.”

Before Frazier had completed his two-year enlistment, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981. The new order “would eventually cause the integration of the military,” and Marines were allowed to request an honorable discharge due to its provisions. Wanting to get out of the South, Frazier took advantage of the opportunity for honorable discharge.

Frazier went back to high school in the fall of 1947. While there, he met and began dating his future wife. After the end of the school year, he took night classes to finish his degree while working full time. He and his wife “got married on October 3rd, 1948.”

By the end of 1951, they had two daughters, and, when Frazier was laid off from his job, he decided to re-enlist with the

Marine Corps, which was in need of personnel due to the Korean War. Frazier “report[ed] to Marine Corps Schools, Quantico, Virginia on 2 July, 1952.” Unfortunately, his wife and daughters stayed in New Jersey.

At Quantico, Frazier mostly worked in supply. After three years, he and his wife had had another daughter, and he chose to get away from the South by taking on a new assignment in California, where his wife and daughters would join eventually him. There, too, he spent most of his time working in supply, and he “really took a special interest in [his] job and got along well with the supply chief, the corporal who was working for [him], and other members of the squadron headquarters.”

His next assignment was in Hawaii, where he led teams that turned disorganized supply warehouses around. He sent the majority of the money he made back to his family, because he could not afford to bring them with him to Hawaii. In January 1959, Frazier moved back to California, working at Barstow Supply Center, which “supported all Marine units west of the Mississippi and in the Pacific area.” He spent four and a half years in the Barstow area, during which time his first son was born. Then, in 1966, he was transferred back to Hawaii. He “really enjoyed the job” there and, this time, he was able to bring his family. By the time they left Hawaii to return to Barstow, another son had been born, completing their family.

At the end of 1967, Frazier was assigned “to report to Okinawa during February 1968.” He was quickly “transferr[ed] …to Vietnam for duty at the Force Logistic Command (FLC),” where he remained for thirteen months. When one of his buddies from Hawaii offered Frazier a place in his hut, Frazier’s race “seemed to be a problem” for one of the other men. Fortunately, “[t]he rest of the men told [that man] he could move out if he didn’t like living there. He didn’t move out and Frazier] moved in.” This man and Frazier eventually “became rather close,” and Frazier recalled that “[h]e wasn’t a bad guy once I got to know him. He appeared to be a good family man who was just a little mixed up. …When we parted I think he realized Black Marines were no better or worse than any other racial group.”

In Vietnam, Frazier continued to work in supply, this time “as supply chief in the general’s headquarters.” Although he experienced middle-of-the-night rocket attacks, he managed to make it through his time in Vietnam. Upon his return, he became the Battalion Supply Chief at the Schools Battalion back in California. After submitting the paperwork to use the GI bill to buy a house in Encinitas, he was transferred to 29 Palms to serve as base supply chief. He “was promoted to Master Gunnery Sergeant before [he] left. That was as high as an enlisted man could go in rank.” Frazier commuted home to be with his family on the we

ekends. Before the yearlong assignment was over, the Marine Corps announced “that all senior officers and senior enlisted men who met certain requirements could apply for retirement.” Frazier “found that [he] met the basic requirements,” and he retired from the Marine Corps on April 30, 1973, after more than 20 years of service.

Since he was only 45 years old, Frazier did not retire altogether, instead choosing to start “a new career as a civil servant.” He worked as a mail carrier for the Post Office before getting the first of several jobs working for the military as a civilian. He worked his way up over the next several years, while also earning two associate’s degrees, before retiring in July of 1989.

After his retirement, Frazier was able to devote more time to his hobbies: “black military history” and “family history or genealogy.” He and his wife got divorced in December 1992. As a retiree, Frazier took advantage of the opportunity to travel “military space available,” going all over the United States as well as to Australia, Central and South America, and Europe. He “met many very nice people in all of the countries [he]… visited.” Frazier found his travels so enjoyable and fulfilling that he moved to be closer to Air Force bases, which “made traveling military space available …more convenient.” At the time he wrote his memoir, he was determined “to continue [his] life style of travel by military air as long as [he was] able.”

On May 15, 2013, Allen Newton Frazier passed away. He was laid to rest in Ft. Rosecrans National Cemetery, in San Diego County, California. We honor his service.

Topics in this story

More Stories

In November 2024, VA's National Cemetery Administration (NCA) officially opened new Green Burial sections at three national cemeteries.

Beginning on Nov. 9, 2024, VA will accept applications for payment of a monetary allowance for privately purchased OBRs and for OBRs provided by a grant-funded cemetery, when the OBR is placed at the time of interment. This allowance may be paid for burials that occurred on or after the effective date of the new authority which is Jan. 5, 2023.

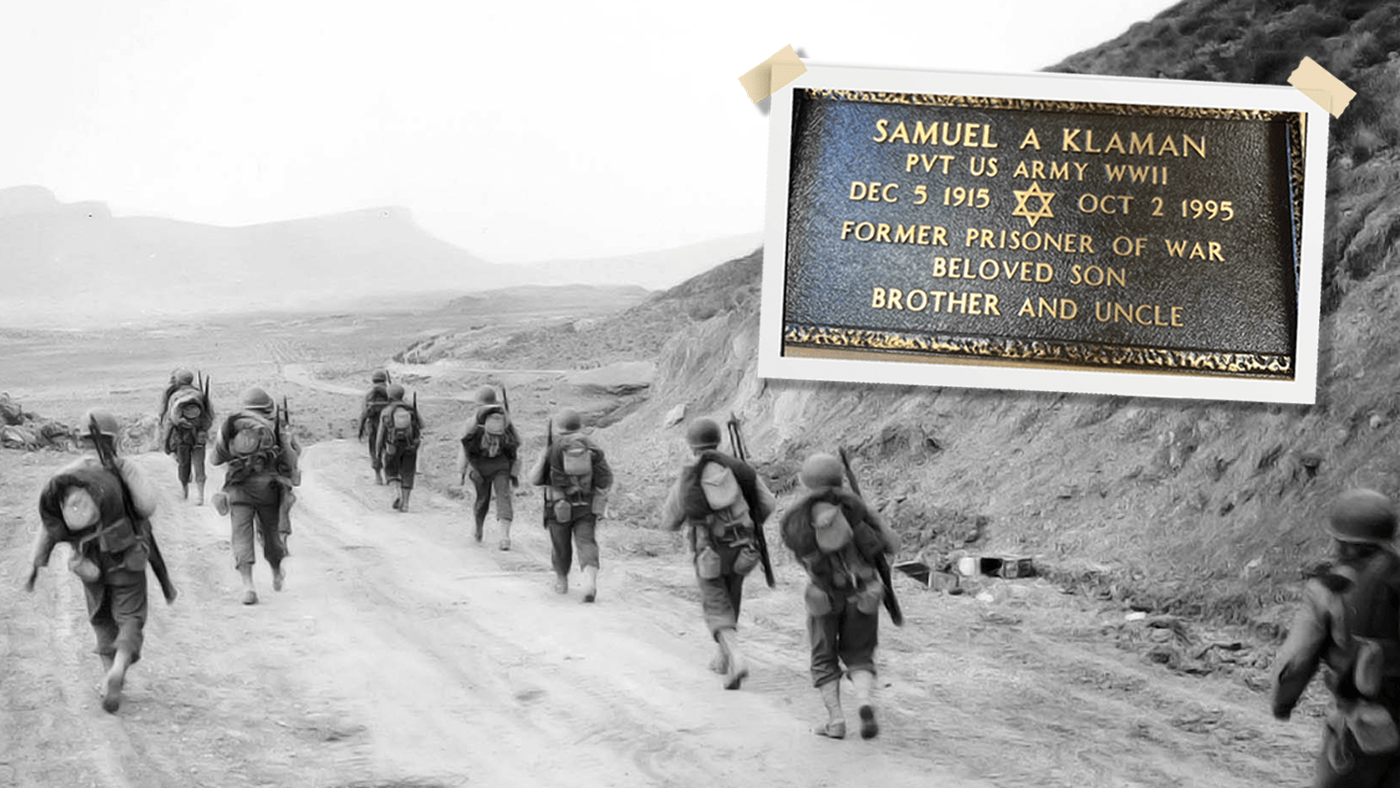

With help from VBA and NCA, an administrative correction honored a WWII soldier's service and Jewish identity.

Master Gunn” Frazier, SEMPER F!! I salute you and your legacy for paving the way. It seems that we traveled in some of the same paths in WESTPAC, my tour took me to Okinawa twice, and Nam. Thanks for your Service!

Thanks for being an “Enduring Volunteer for Our Defense” !!!

I Salute You and your wonderful life, MGYSGT FRAZIER!

So good to read of a REAL AMERICAN nowadays.