As far back as anyone can remember, African American Veterans and citizens in the Mississippi River towns of Vidalia, Louisiana, and Natchez, Mississippi, have come together on Memorial Day to honor military service to the country and pay respects to loved ones interred at the Natchez National Cemetery.

The three-day patriotic weekend includes placing of flags by members of the community at the gravesites of the nearly 7,000 servicemen and women interred at Natchez; and two memorial church services — one led by the Women’s Relief Corps, a women’s auxiliary organization that was established nationally in Denver, Co., in 1883. Tthe local Vidalia chapter was formed on June 13, 1898.

Finally, on the third day, Memorial Day, the American Legion Post 590 of Vidalia leads approximately 500-750 marchers on a grand procession that begins at the Zion Baptist Church in Vidalia goes over the 4,200 ft. Vidalia-Natchez bridge spanning the Mississippi River through the streets of Natchez then uphill the last mile to the Natchez National Cemetery which sits high on the bluffs overlooking the river. By the time they’re done, the grand parade has traversed a little over 4.5 miles through the streets where slaves were once sold and the United States Colored Troops (USCT) once patrolled. It’s a tradition like no other in the country with roots tracing back to 1866, immediately after the end of the Civil War and it’s known locally as “The 30th of May.”

In 2015, as a graduate student in history at Jackson State University, I began researching this Memorial Day tradition in the deep south. I learned about it through an NCA colleague, Orin Hatton, program analyst in the finance and planning division. He had spoken at the Natchez Memorial Day program in 2014 that takes place immediately following the grand parade.

I shared with Orin that I was looking for a research topic that somehow incorporated VA national cemeteries. I also had in mind that ideally I wanted to do local history about African Americans since I was attending a historically black college and university. When Orin told me about what he experienced in 2014, I realized that I had just “hit the jackpot.” My research paper covered all three objectives.

One of my first phone calls I placed was to another NCA employee, Sheila O’Neal Smith, a cemetery representative at Natchez and a native of the community. “They’ve been marching as long as I can remember,” Sheila told me. Now I started to get excited. Next, I looked online at newspaper accounts and made contact with Darrell White, director of cultural heritage, at the Natchez Museum of African American History and Culture. Both confirmed that this event had been going on a long time. Just how long was yet to be discovered.

From October 2015 through April 2016, I took several trips back to Mississippi to conduct research at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson and conduct interviews with participants in the Memorial Day tradition. I found an article dated July 7, 1867, in the Natchez Democrat that wrote about a grand procession attended by over 10,000 people, (black and white), marching bands, glee clubs and guest speakers. Then I discovered a similar event that took place a year earlier on July 4, 1866, at the Longwood Plantation in Natchez which ended prematurely due to rain.

For the immediate 25 years after the Civil War, Memorial Day celebrations in Natchez were attended by both black and white citizens, but by 1890 two distinct celebrations began, one black and one white. A year earlier, in 1889, to ensure that their military service to the country would not be forgotten, black USCT veterans, who belonged to the Federal Memorial Association, made their first procession to the Natchez National Cemetery. The Federal Memorial Association became defunct the next year when the Grand Army posts were formed.

Following that first parade in 1889, African Americans in the region committed to marching every year. Newspaper accounts confirm the parade’s existence. By the turn of the century, they certainly had become the “lone” voice of Union victory in the region.

My research into this event took another great turn when I discovered an interview NCA had conducted in the late 1990s with WWII Veteran Clarence Randall Jr. Randall was the commander of American Legion post 590 at the time and remembers marching in the parade, “ever since I was a little, 5 or 6, I guess.” He was born in 1915 which dates his participation to 1921. Then I was provided another interview with WWII Veteran Luke Henderson, who was the commander of American Legion post 226 in Natchez, who led and organized the event soon after his return from the war. He was known in the community as “Mr. 30th of May.” On Memorial Day, May 28, 2001, 91-year old Luke Henderson saluted the flag for the last time and, six hours later, he died. He was laid to rest at the Natchez National Cemetery.

By March 2016, I had completed most of my research having conducted interviews with WWII Veteran Frank Williams Jr., who dates his participation to the 1930s and chairwoman of the 30th of May committee, Laura Ann Jackson and other participants. Jackson remembers sitting on the fence as a young girl watching the white parade and ceremony take place after the black celebration was complete.

I then entered my project into two history conferences in Mississippi, Phi Alpha Theta Historical Honor Society and the Creative Arts Festival at Jackson State University. After winning “Best Paper” at both, I decided I wanted to film and document this event, which just happened to fall on May 30 last year. I realized that 2016 was the year to film it. I connected with a colleague/cinematographer I had known when I was the public affairs officer at the G.V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center in Jackson, Mississippi, from 2012-14 and we decided to document the entire weekend. We filmed for four days. Then I returned to Alexandria, Virginia, and from a distance of 800 miles we put this 28-minute documentary together.

By September 2016, the documentary was complete and I began entering it into film festivals and film competitions. The film has screened in Birmingham, England; Calcutta, India; Houston, Texas; Hagerstown, Maryland; San Diego and Hollywood and on Memorial Day weekend will screen at the 11th Annual GI Film Festival in Washington D.C. on Sunday, May 28 at 5:30 p.m. at the U.S. Navy Memorial Theatre. The film will also air on Mississippi Public Broadcasting on Sunday, May 28 at 4 p.m. To date, the film has received seven awards to include “Best Documentary Short” and “Best Message” at the Top Indie Film Festival.

It’s been a genuine honor to share this amazing story of patriotism and tradition with audiences around the world and country. Not only is the logistics of this event remarkable (prior to the bridge being built in 1940, participants would ferry across the Mississippi River), but the connection to this specific date, May 30, is unique in African American remembrance. There are many dates — such as July 4, September 11, November 11, December 7 — that Americans connect their memories to. For Americans of different ethnicities, there are other days of celebration, such as Cinco de Mayo (May 5) for Mexicans, St. Patrick’s Day for Irish and Juneteenth (June 19) for African Americans.

As part of my research, I reference two authors who traveled the country searching specifically for African American freedom celebrations. They discovered several, but not the 30th of May. The credit goes to the citizens of this region for contributing significantly to American history by continuing this tradition, and for ensuring that, in the collective memory of the region that black military service to the country is not forgotten. It’s known as the 30th of May. It’s a tradition like no other in the country.

Topics in this story

More Stories

In November 2024, VA's National Cemetery Administration (NCA) officially opened new Green Burial sections at three national cemeteries.

Beginning on Nov. 9, 2024, VA will accept applications for payment of a monetary allowance for privately purchased OBRs and for OBRs provided by a grant-funded cemetery, when the OBR is placed at the time of interment. This allowance may be paid for burials that occurred on or after the effective date of the new authority which is Jan. 5, 2023.

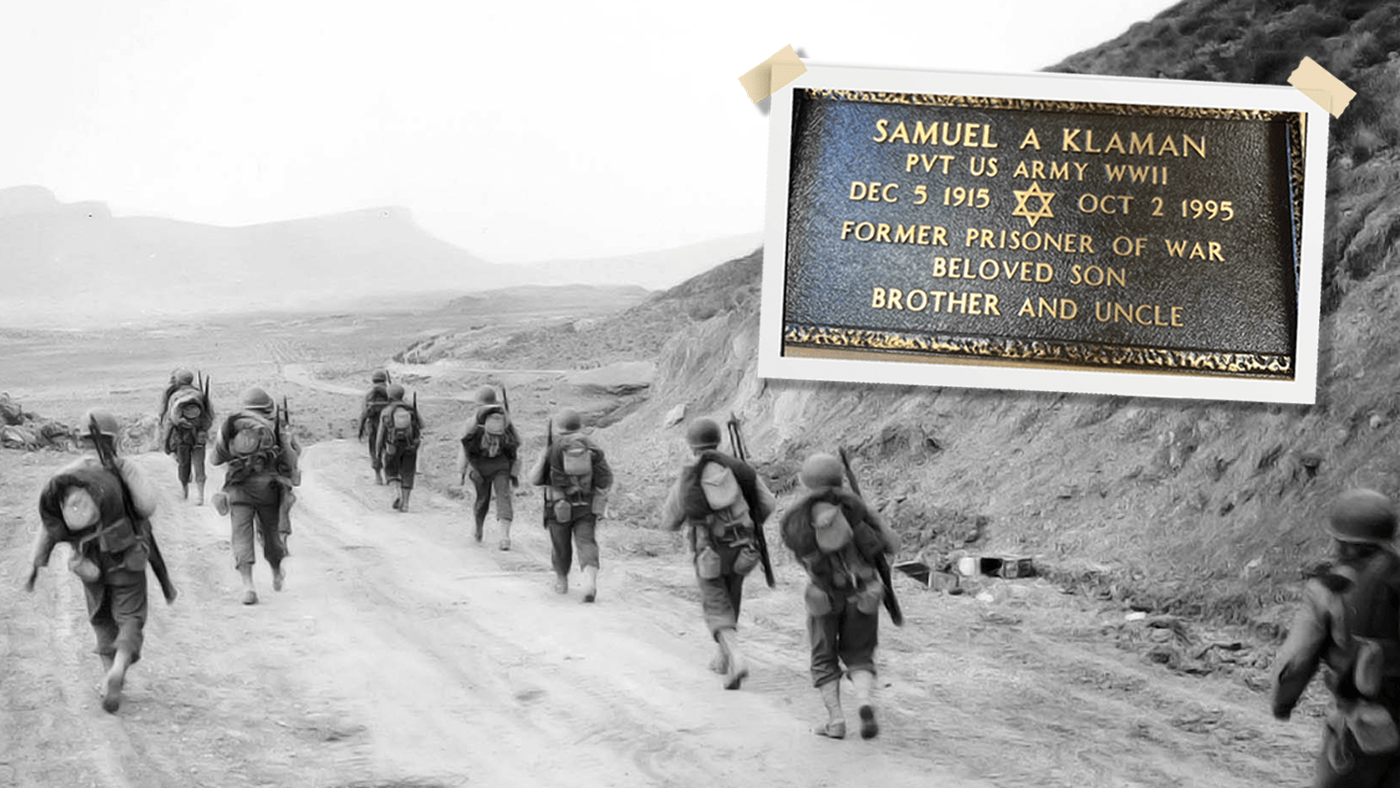

With help from VBA and NCA, an administrative correction honored a WWII soldier's service and Jewish identity.