Many know the history of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, but few are aware of the tremendous effort it took to capture John Wilkes Booth. Fewer still know the story of the brave men who gave their life in that pursuit.

Toward the end of the Civil War, Confederate forces evacuated Richmond, Virginia. Within two weeks, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his troops. As Washington celebrated, Booth attended a Lincoln speech on April 11, 1865. He reacted strongly to Lincoln’s suggestion that he would pursue voting rights for freed blacks. Booth allegedly told his co-conspirator David Herold, “Now, by God, I’ll put him through.” Three days later, at Ford’s Theatre, Booth made good on his threat. On Friday, April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated by Booth.

“After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln there was a massive effort to hunt down John Wilkes Booth,” said Kenneth Holliday, a learning resource officer for the National Cemetery Administration Veterans Legacy Program. “This manhunt took place over the course of a few weeks in April 1865. A serious concern at the time was of Booth crossing the Potomac River and going back into Virginia.”

Union troops were immediately sent into southern Maryland, and ultimately to Virginia, in pursuit of Booth. Among those was a contingent from the Army Quartermaster Corps, patrolling the river in search of a boat ferrying Booth across the Potomac. Unknown to the Quartermasters, Booth and Herold had already crossed the Potomac on April 22, 1865.

This Quartermaster contingent was comprised of civilian employees from the Alexandria Fire Department. They were chartered by the U.S. Army, who had taken a military interest in the search and capture of Booth. Unfortunately, this mission would have fatal, and unforeseen, consequences.

Two ships were involved in the tragic events of April 23-24, 1865: the USS Massachusetts and the Black Diamond. The Massachusetts was heading to Norfolk, Virginia, where it was to be deployed for duty in North Carolina.

According to historical accounts, the Black Diamond was said to have had only had one light showing. Not unusual for a ship on picket duty, but it also meant it wasn’t seen in the darkness as the Massachusetts made its way downriver toward Norfolk. Around midnight, on April 23, the Massachusetts and its 400 passengers and crew collided with the Black Diamond and its crew of 20. Eighty-three men from the Massachusetts died on the river that night. As a result, many of the bodies were never recovered.

Of the 87 people who died during the collision, four were from the Black Diamond. Peter Carroll, Christopher Farley, Samuel Gosnell, and George Huntington all lost their lives in pursuit of Booth. Within 24 hours of their deaths on the Potomac, Booth was also dead.

The four Alexandrian firemen who perished in the crash were bestowed the honor of burial in the Soldier’s Cemetery in Alexandria, now known as Alexandria National Cemetery.

“These four civilians died while in the service of their country,” Holliday said. “They were buried among Union soldiers, who also gave their lives for their country. Leaders at the time thought they should receive honors for their sacrifice; that is why they are buried in a national cemetery.”

In 1922, the federal government placed a granite boulder at the cemetery commemorating the deaths. In the 1950s the deteriorating headstones for each of the four men were replaced by new markers bearing the same design as those used for Union soldiers buried at the cemetery.

Though they were unable to complete their mission, we honor the sacrifice of the men who risked their lives to bring President Lincoln’s assassin to justice.

Shawn D. Graham is a public affairs specialist with the National Cemetery Administration. Shawn is a retired U.S. Navy chief petty officer who served his country for nearly 21 years. He has deployed numerous times to remote regions to include Afghanistan and Uganda.

Topics in this story

More Stories

The findings of this new MVP study underscore the importance and positive impact of diverse representation in genetic research, paving the way for significant advances in health care tailored to Veteran population-specific needs.

VA reduces complexity for Veterans, beneficiaries, and caregivers signing in to VA.gov, VA’s official mobile app, and other VA online services while continuing to secure Veteran data.

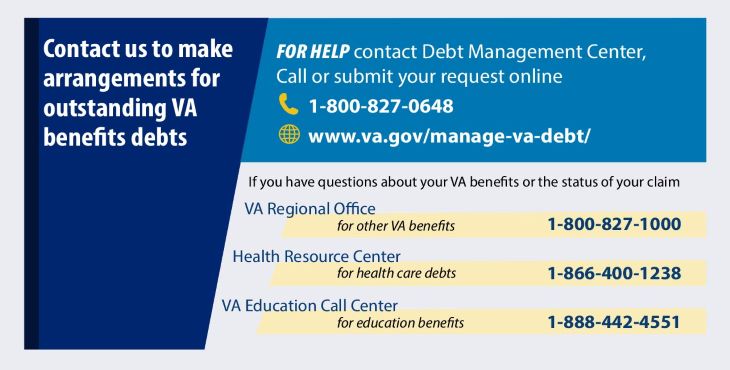

VA has resources available to ensure natural disasters do not make the already challenging situation of owing a VA debt worse. If you are experiencing financial hardship and are unable to repay your VA debt because of a natural disaster, relief options are available.

King George xv,Cornwallis ictj,NY, USA.

Your rude and missing the point here on what they are talking about. Just how these folks got over shadowed during this search and to honor them.

I was unaware of this incident and its relationship to the assassination. You have added to my knowledge of the case.

I’m a family history researcher who has found two connections to Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. My mother was a distant cousin of Henry Rathbone, the Army officer who was with the Lincolns in Ford’s theater, and was stabbed by Booth during his escape. My father was a cousin to Colonel Nelson Bowman “NB” Sweitzer, the officer in charge of the New York troops searching for Booth. Both of these connections are incredible, especially since my 20th Century family are all middle class Americans, most of whom never attended college or held white collar jobs, and none have been famous or rich.

A better account for the actual search for Lincoln’s assassin rather than a coincident boat accident can be found in the excellent book, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson