By Mike Richman

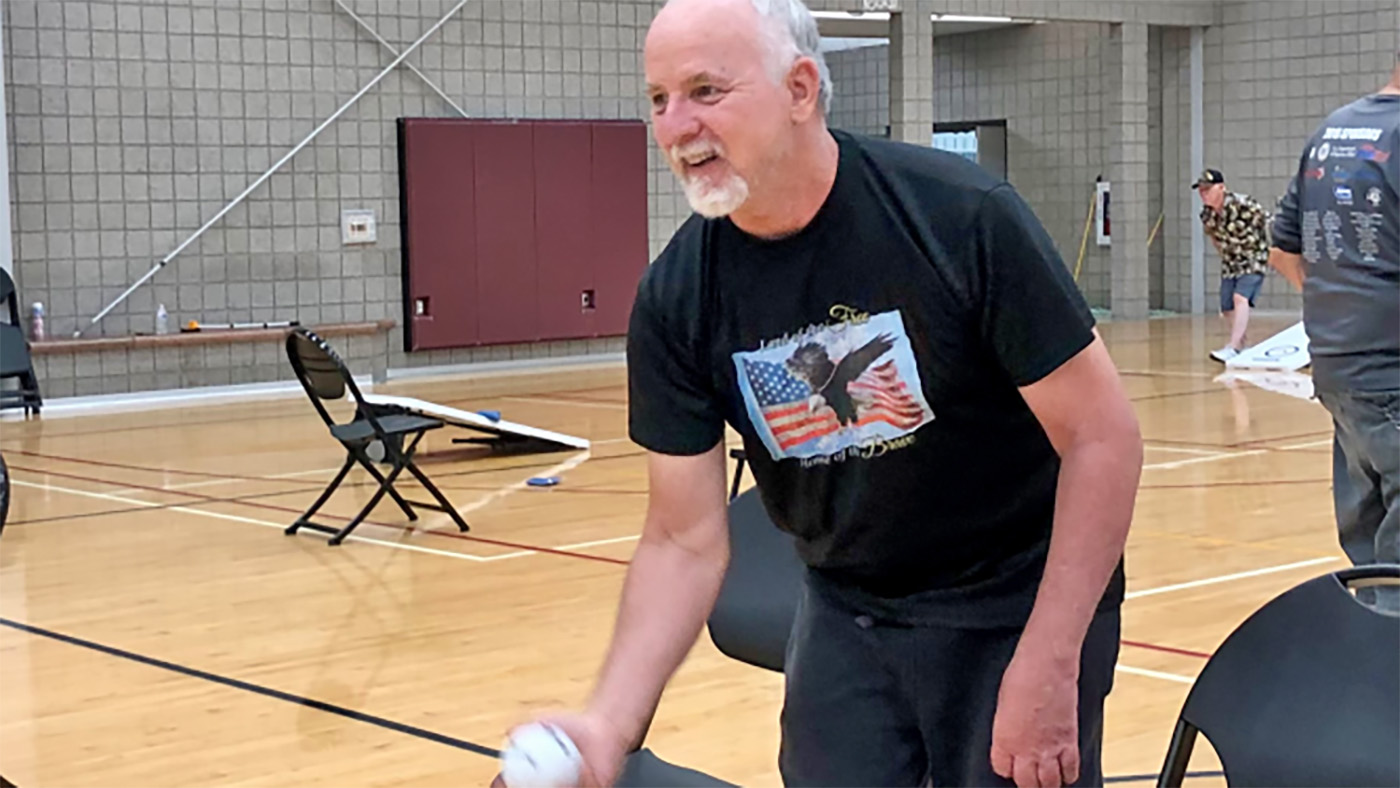

It’s the evening before Bill Misner’s big day of competition at the National Veterans Golden Age Games in Anchorage, Alaska. He’s sporting a baseball cap that says “Native American” and a T-shirt with the words “Chief Gary Batton” on it.

Batton is chief of the Choctaw Nation, which recognizes Misner as an honorary tribal member. Misner is one-quarter Choctaw.

Misner proudly competed at the Golden Age Games on behalf of Choctaw Nation. He hopes that his presence sends a critical message to his fellow Choctaw people.

“Diabetes is a big health issue with [the Choctaw], as it is with other tribes,” says Misner, a Marine Veteran who served in the 1960s. “My impetus is to drive home the fact that we need to work out. For me to be able to come here and do that … I’m living it. I tell them, if I can do it, anybody can.”

Misner is a huge role model for Choctaw Nation. Competing Sunday in the men’s 75-to-79 age group, he earned a trifecta of gold medals: 1,500-meter run, 400-meter run, and 100-meter sprint. He completed all three of those events in just a one-hour span. He also pocketed a silver in the javelin and a bronze in the 25-meter sprint swim.

His performance topped his results in his only other appearance at the Golden Age Games in Detroit in 2016, although what he put forth in the Motor City was outstanding in itself. He won two gold medals (400- and 1,500-meter runs), two silver (javelin and 50-meter swim), and one bronze (50-meter swim) in Detroit.

At the time, he was at the bottom of the 75-to-79 age group. In the 2019 games, he was at the upper end of that demographic at 79 years old. He thus knew that a rigorous training routine would be key to him excelling in Anchorage.

He devoted six days a week to training in his hometown of Spokane, Washington. He ran most of the time and swam one or two days a week. He didn’t start practicing the javelin throw until about six weeks before the event, getting help from a track and field coach at a junior college in Spokane.

“The coach was kind enough to teach me and patiently show me things I should be doing,” he says. “In the pool, I swam all sprints. In the 25, I’d go from one end of the pool to the other as fast and as hard as I could. I’d try to keep my head down and not breathe because that slows you up.”

While representing Choctaw Nation, Misner witnessed an important intangible at the Golden Age Games in Anchorage. The annual VA sports event attracted more than 700 Veterans and ended on Monday after five days of competition.

“The camaraderie is awesome,” he says. “We all compete. But we all hate losing to one another. Once it’s over, however, everyone knows we went through something together. The camaraderie has been just beautiful, very beautiful.”

Misner, who is incredibly fit for a man of his age, adds that each Veteran who participates in the games understands that “you’ve got to keep moving because exercise is part of the solution” to many health problems. “Everyone will tell you the same thing, he says. “You’ve got to keep doing it. After they try it, they find out that it helps them.”

When not involved in athletics, Misner is active with the American Indian Veterans Advisory Council, a VA body that assists Native Americans with such issues as homelessness, medical needs, and relations with VA. He’s one of two Veterans on the council in the Spokane area. The Mann-Grandstaff VA Medical Center in Spokane hosts meetings that focus on Native American Veteran interests in eastern Washington, western Idaho, and some of Montana. Tribes in that region, including the Spokane, the Coeur D’Alene, the Nez Perce, and the Yakama, send representatives to the meetings in hopes of learning about important issues that they can share with Veterans in their tribes.

“VA has a lot of bureaucracy,” Misner says. “Native Americans do not like red tape. They’re very simple and to the point: Tell me what to do, and I’ll do it. They’re very discouraged with the relationship with VA. So they quit and give up. That’s not the ticket. They need to go back and go through the process. They need to follow the process in order to get to the thing that they need. It might be a home. There are advocates that they can speak with. There are chaplains, social workers. As part of the council, we explain the services VA has. We’re like an intermediary. We have psychiatric workers show them what services are available. They encourage Veterans, especially the Native Americans, to come in and take advantage of VA services.”

Mike Richman is a writer and editor in VA’s Office of Research and Development. He joined VA in 2016. He previously worked at the Voice of America, one of the U.S.-funded broadcast agencies.

Topics in this story

More Stories

West Virginia mom builds confidence at the National Veterans Wheelchair Games.

Air Force Veteran Mark Wager overcame a stroke and is now competing in the 2024 National Veterans Golden Age Games.

Clinic offers a wide range of adaptive sports activities tailored to Veterans with physical and mental challenges.