On Dec. 8, 2020, U.S. Army Veteran David Harker will celebrate his 75th birthday. He may recognize the accomplishment while on his daily five mile walk, or by taking a drive in his 47-year-old car – a 1973 Corvette he’s owned since it was given to him by classmates when he returned from Vietnam after spending more than five years as a prisoner of war.

A native of Lynchburg, Virginia, Harker is the third of seven children. He was an athlete in high school and received his associate’s degree from Bluefield College before transferring to Virginia Tech in 1966. By 1967, however, his fortunes had changed.

Drafted

“I was doing my junior year at Virginia Tech and my grades were low, so I had to take a quarter off in 1967 and during that time, because I wasn’t a full-time student, I had to let the government know. They got me,” he said.

When the draft notice came, Harker’s father, an electrical engineer took the news hard.

“My dad was really upset. He had worked for a power company during World War II and so was exempt from the draft,” Harker recalled. “I didn’t think about the possibility of being killed. My dad’s supervisor said he could get me in the National Guard, but I thought that would be shirking my responsibility. I was called on to serve my country and that’s what I was going to do.”

After basic and advanced infantry training, Harker was approached and offered an opportunity to go to Officer Candidate School.

“I was interested in flying helicopters, but they said I’d have to extend for another year or two, so I said, ‘no, I’ll do my two and go home’.”

Heading to Vietnam

The trip to Vietnam brought Harker through Hawaii, and Guam, before landing in Vietnam Nov. 15, 1967. The recollection of arrival is still fresh even 53 years later.

“There were men on the airstrip who had finished their year and were going to take the plane we had arrived on back home. So, they open the door and it was such a rude awakening when the door opened. The oppressive heat – and I’m sure Vietnam Vets will tell you – the country had a smell of its own.”

The soldiers on their way home watched them deplane and Harker heard them say, ‘there’s my replacement.’

“They wished us well,” Harker said.

Although trained on a vehicle-mounted recoilless rifle, Harker was made an infantryman upon arrival in-country and reassigned from the 9th Infantry Division to the 196th Light Infantry Brigade. Six weeks later, he was a POW.

“I was in the 3rd of the 21st in an area of operations at Que Son,” Harker said. “We operated out of a fire base, with one company pulling security while the other three were out doing search and destroy missions. While out, we’d move about 1,000 meters a day and get resupplied every fourth day with c-rations if the helicopters could get through.”

As a 22 year old, Harker was among the older men in his unit. His commanding officer, Capt. Roland Belcher, told the company while they were enjoying in-country R&R at brigade headquarters in Chu Lai, that he was proud of the work they were doing.

“Captain Belcher had been in a province southwest of Saigon where we were providing security for elections,” Harker said. “He said it meant a lot to him that we were able to do that – to make sure those people could go to the polls and not get hurt. I remember that because he died in the rice paddies when we were ambushed.”

Harker’s first sergeant, nicknamed Top, was a 41-year old Veteran of World War II and Korea who had earned a Silver Star before joining the company.

“After the ambush, he was the ranking person and he held us together.”

Capture

Harker and his company were on patrol when they broke contact with the enemy in a creek bed. The North Vietnamese unloaded on the unit and killed two men. As the most forward man, Harker was pinned down.

“I’m thinking, ‘I’m going to die.’ Top is behind me telling me to switch to auto and fire. They tried to get behind us and eventually I hear a Vietnamese voice and do a 90 degree and within arm’s reach at the top of this creek bank is an NVA soldier with a pith helmet and Top is there with no helmet. There’s a guy with a rifle telling me to get up. The NVA are stripping everything off us – anything they can use. I tried to bury my M-16 in the creek bed but I think they got it.”

After being taken, Harker was left with a soldier with a sidearm who walked in front of him, leading him away from the creek.

“I thought it was odd he was in front of me and I had been taught that you always try to escape. Next thing I know my hand is over his mouth and I have his arm at his side. I know I have to kill him and do it silently, but his bayonet won’t come out of the scabbard, and by that time my hand has come off his mouth and he’s yelling bloody murder. Before I could get his .45, he stabs me in the side with his bayonet. By that time there are a bunch of rifles pointing at me. I’m surprised they didn’t just shoot me, but they took some commo wire and duck-winged me that night.”

Of the 15 men who entered the rice paddy that evening, only four made it out. More men would join Harker in his prison in the Trung Son Mountain Range where he would spend the first three years of captivity. By Harker’s estimation only about 150 U.S. soldiers were captured in South Vietnam – most of whom were taken during the Tet Offensive.

Harker’s first prison was in Quang Nam Province, a difficult, mountainous country that made food scarce and meant deplorable living conditions for the POWs.

“We buried nine Americans there,” Harker said. “That’s how horrific our living conditions were. We had very little to eat so people died from starvation, infectious diseases – malaria was rampant – dysentery. Between September of 1968 and Jan. 4, 1969, we buried six, including the youngest person we had there, a 19-year-old Marine.

“That first year of adjustment to jungle life was really hard on us. You didn’t know what to do. At first you looked out for yourself, but as time went on, you got more altruistic – you realize, it’s not about me, but about the guy next door and you realize you had to take care of each other. We came together really well in that respect.”

During the Vietnam War only one American doctor was ever taken prisoner. Hal Kushner, who grew up in Danville, Virginia, was injured in a helicopter crash in late November. By Dec. 4, North Vietnamese forces found him and marched him toward the camp where he found, according to a speech he gave in February 2018, “four of the saddest looking American creatures I had ever seen in my life.”

“They wouldn’t let him practice medicine,” Harker said of Kushner. “We couldn’t call him doc, but he was a big source of information and help to us. He led the way and showed us how to nurse and take care of men, and that became our goal – to make people in their last hours and days as comfortable as possible – it was our mission, and he was a big inspiration to us.”

In the mountains the men had to forage for food, mostly the manioc root, also known as kasava root.

“There wasn’t a place to grow food, so most of our calories came from manioc,” Harker said. “We were under a 1-to-1 prisoner-to-guard ratio, and the guards would trade manioc and so we would put baskets on our backs and go back and forth over miles of mountain trails carrying 70-80 pounds of root. It’s amazing to think that we could even do it, but we did what we had to do. The little bit of rice they gave us as a ration wasn’t enough to keep a bird flying, so the roots kept us going.”

The guards of Trung Son didn’t physically abuse their prisoners. They didn’t need to.

“We were separated from civilization in the middle of nowhere and we couldn’t communicate; had no food, and no medical attention – that’s torture enough for an individual. We were interrogated when we were captured,” Harker said, “but we knew the Code of Conduct and so we’d give that information. But they’d have a guy with a lantern and they’re asking for information about your unit, it’s size, and I just kept repeating. They didn’t pursue it much. They wanted to get us away from the battlefield but a few days later they did it again. When you have a rifle and you’re in front of the enemy, it’s different. But if they put a blindfold on you and all you can hear is round being chambered – that’s different too. In the north they beat pilots and used a lot of torture techniques.”

Moving day

On Feb. 1, 1971 there were a dozen men still alive in the mountains and they were taken in groups of six to begin their march north up the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Harker watched battalions of Vietnamese troops heading south during the 60-day march, as they ground out 10 to 15 miles a day. During the journey an interpreter would give them extra rice.

“He was a military guy who had fought in Laos as a 17-year old in the early 1960s, and he looked out for us. I think he understood the condition – there was a common situation and appreciation among soldiers.”

“We’d get to a camp every day where we got hot white rice – better than we had at the mountain camp. The next morning they’d put a ball of rice on a banana leaf and we’d carry that with us for lunch as we moved. Eventually we were put on a train, in a box car, and taken to Hanoi, to Plantation Garden, an old French plantation with bars in the walls. We were kept in a 15×17 warehouse – six of us on a wooden pallet. Unlike the mountain camp we couldn’t roam around, and the boredom would overtake you and the heat was oppressive, but we had plenty to eat compared to the south. We also had better medical care there as they had a doctor to attend to us.”

In October of 1972 the Vietnamese allowed prisoners to be outside together for the first time since they arrived, and it looked like the war might be over.

“We had a communication system where we’d put a note on the lid of the waste bucket, or use the tap code, and we had to do that because we were only allowed out of our cell for about an hour a day, and never more than one cell was let out at a time. So, when they let everyone out, and then gave us reading material, they knew it was over. Or they thought it was, because before you know it, the doors are all slammed shut again.”

Soon after, Linebacker II started. From Dec. 18-29, 1972, the U.S. Air Force conducted an operation called Linebacker II, a ‘maximum effort’ campaign to destroy targets using B-52 heavy bombers that dropped more than 15,000 tons of ordnance on more than 30 targets.

“B-52s bombed all night long after talks broke down. The SAMs (surface-to-air missiles) shot down a bunch of planes on the third night, after they figured out the flight patterns, and one night they pulled up a deuce and a half and told us to crawl in the back. We thought we were being taken to China.”

Harker would spend his last three months as a prisoner at the Hanoi Hilton.

Repatriation

Half a world away, in Paris, a peace accord was signed January 27, 1973, and soon after Harker and other American POWs heard the news they had longed to hear.

“We were ecstatic,” Harker said. “We’d hear doors open and activity and they came and said, ‘you’re going, and you’re going, and you’re going’ dividing us up into groups that would be repatriated. They gave us western clothing and a travel bag and when they pulled us out of a holding cell wearing our red-striped pajamas we were given the clothes. By noon, nothing had happened. They gave us food and told us the peace agreement was broken – and we were right back down in the depths of despair. But a few days later we got out.

“I remember saluting an Air Force general who was sitting with a North Vietnamese officer, and when we saluted, we had been officially repatriated. On the plane home, the pilot told us when we had entered international airspace and there was a great cheer.”

The cheers continued when they landed in the Philippines, Hawaii, and Andrews AFB, Maryland. From Maryland, Harker went to Valley Forge in Pennsylvania where he went through medical treatment and rehabilitation, and he was reunited with his family.

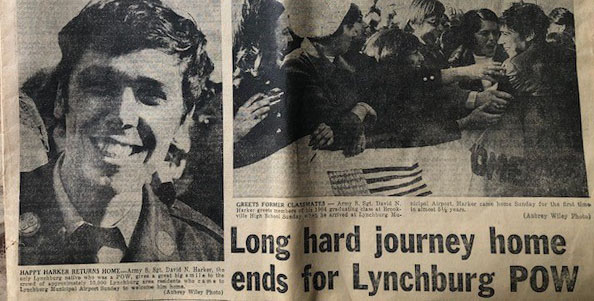

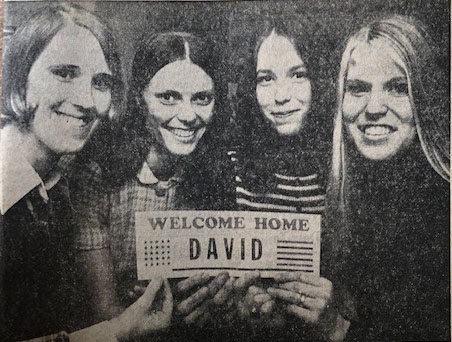

“It was different,” Harker said. “I had brothers who were married, and children had been born, but it was exciting coming home. A private airline flew me and my father back and the local TV station had sent a reporter who interviewed me all the way back. There must have been 10,000 people at the Lynchburg airport when we arrived – I had no idea there would be that welcome and response – my big extended family – the high school band was there. It was a long journey and I was glad to be home and for them to be there for me meant so much. I was led to a blue 1973 Corvette and handed the keys. A group of school mates had gotten together and sold bumper stickers for a dollar each to buy me a car and they handed me the keys and a check for $1,100.”

Being home with his family, Harker said he learned how much anxiety and frustration and worry his parents went through while he was captive.

“Every POW gets a casualty assistance officer whose job it is to let the family know when they hear something – anything – about their son,” Harker said. “My family never heard anything from their CAO. It wasn’t until 1969, when three prisoners were released that they knew I was alive. My parents found out that a couple of those who were released were at Fort Jackson, and so they went there and got onto base and met with them and heard from them that I was alive. That’s all the knew for five years. So they became involved in the National League of Families who organized and tried to have some involvement with North Vietnam to get information about prisoners and try to make the process more transparent as far as information was concerned.”

Life after war

After he returned from Vietnam, Harker took some time off, but eventually returned to Blacksburg and finished his business degree from Virginia Tech in 1976 and found his way to work as a probation and parole officer. In 1977 he married Linda, his high school sweetheart whom he had dated since 1962.

His family now includes his two children, Megan and husband Mike, and Adam and his wife Anza. David and Linda also enjoy their grandchildren: 13-year old Emily, 11-year old Ethan, and 6-year old Eli, children of Megan; and Adam’s 23-month old daughter Ava.

While Harker is open to discussing his time in Vietnam to serve as an education for younger people, he said it was a part of his life that he’s put behind him.

“Kush and I talk about that all the time – we’re not professional POWs. By the grace of God and the help of other men, we made it out. We all serve our country one way or another. This country is what we love. My life has been a real blessing since then, and the staff at the VA hospital, what they do is marvelous, and I appreciate each one of them. I know they have a heart for those Veterans, or they wouldn’t work there,” Harker said. “I love the Veterans, too, and appreciate their service, and institutions like the VA are a great service to our country.”

In the early 2010s Harker had the Corvette he received in 1973 – the car he and his youngest brother Louie drove across the country after his return – restored. He still drives it today.

“I think of all the love behind it every time I drive it.”

Topics in this story

More Stories

Summer Sports Clinic is a rehabilitative and educational sporting event for eligible Veterans with a range of disabilities.

Report examines the input of over 7,000 women Veterans: They are happier with VA health care than ever before.

Veterans and caregivers, you can help shape the future eligibility requirements for the VA Caregiver Support program.

I remember the day when David returned to Preston Glenn Airport in his hometown of Lynchburg, VA. Myself (a Brookville High School graduate) along with thousands of people and the Brookville High School Band were there to cheer David on his return home. A brand new Mustang was awaiting his arrival. The new Mustang shone as bright as David’s smile. It was a day I will never forget.

Great story, I hope to meet you someday at an American reunion. David’s story is so impressive to even survive the starvation and torture. WO Frank Anton may have been with you.

God Bless and keep driving that Corvette!!

John “Doc” Hofer B 5/46, 198th Bde, Americal