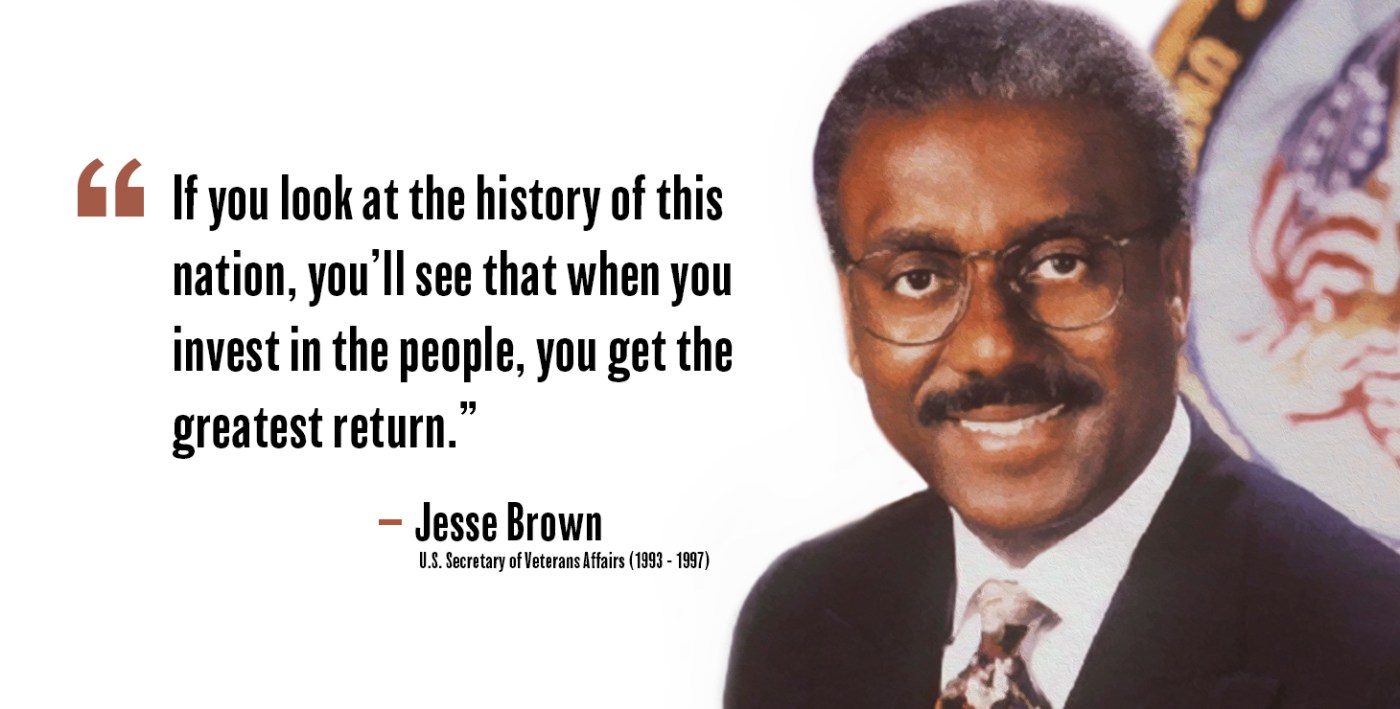

This February, while the nation celebrates Black History Month, VA’s Homeless Programs Office (HPO) recognizes that our history of accomplishments preventing and ending Veteran homelessness is built on the work of trailblazing Black men and women. Among these notable individuals is Jesse Brown, a decorated disabled Vietnam Veteran who, in 1993, became the first African American Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Secretary Brown, who wanted to be known as the Secretary for Veterans Affairs, was an advocate, visionary and leader whose commitment to Veterans led to an expansion of VA benefits and programs. Along with delivering on a number of far-sighted goals to innovate within the Department, Brown extended disability payments to Veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder and Agent Orange exposure, expanded services to women Veterans, and addressed the needs of Veterans experiencing homelessness.

Upon nominating Brown for VA Secretary, President Clinton told USA Today that Brown “knows first-hand that those who have given of themselves to fight for this country deserve the best this nation can offer.” In 1965, while serving as a Marine in Da Nang Vietnam, Brown was wounded in combat, leaving his shattered right arm partially paralyzed. During his recovery at Great Lakes Naval Hospital outside of Chicago, Brown worked with the Disabled American Veterans (DAV) to file for VA benefits. With few jobs available for Black people that did not involve manual labor, the prospects for a Black man with the use of only one hand were bleak. However, as Brown’s mother Lucille told the Chicago Tribune, “He adjusted, and he never felt handicapped or sorry for himself. He made up his mind to try to find out what to do in life.”

In 1967, Brown took a job as a DAV national service officer, launching a 26-year career that culminated in his appointment as DAV’s first African American executive director in 1988. Throughout his tenure with DAV, Brown continually pushed Congress, the White House, and other federal agencies to support legislation that improved the health and welfare of disabled Veterans and their families.

Brown’s uncompromising advocacy of Veterans’ rights made him an ideal choice to head VA at a time when the agency was besieged by criticism and calls to shrink its scope and reduce Veterans’ benefits. Firm in his belief that Veterans were the only group of people who actually paid for the benefits they receive, Brown tackled the plight of homeless Veterans, convening the first National Summit on Homelessness Among Veterans in 1994. He reinvented VA’s homeless assistance network, promoting a continuum of care approach to serving homeless Veterans in the community. With community partnerships, he helped develop medical services, transitional shelter, permanent housing, and employment programs for those with abuse, psychiatric, and physical disorders.

Brown’s efforts on behalf of homeless Veterans put him in the spotlight, and he was named co-vice chair of the Federal Interagency Council on the Homeless, a role that allowed him to make addressing the needs of homeless Veterans a national priority.

When Brown retired in 1997, VA’s funding had increased by almost $1 billion more than the previous year’s spending plan in an era of rampant budget cutting and a declining Veteran population. Further reflecting Brown’s belief that “the way we treat our Veterans is an indication of who we are as a nation,” VA became the nation’s largest provider of services for homeless people.

Secretary Brown died on August 15, 2002, of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig’s Disease. In May 2004, the West Side VA Medical Center in Chicago was renamed the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center, becoming the second of two VA facilities named after an African American Veteran.

Brown’s vision of ending the national tragedy of Veteran homelessness lives on through the work of Black leaders and Veterans’ advocates. Ralph Cooper, co-founder of the National Committee of Homeless Veterans; Andre Simpson, executive vice president and chief operations officer of Veterans Village of San Diego and NCHV board member; and Wendy Charece McClinton, CEO, Black Veterans for Social Justice are only a few who are building on Secretary Brown’s legacy.

Through their work and the work of others, VA’s HPO offers a wide array of services and initiatives connecting homeless and at-risk Veterans with housing solutions, health care, community employment services, and other required supports. This large integrated network of homeless assistance programs has helped more than 80 communities and three states – Connecticut, Delaware, and Virginia – effectively end homelessness among Veterans. Since 2010, more than 850,000 Veterans and their family members have been permanently housed, rapidly rehoused, or prevented from falling into homelessness through HUD’s targeted housing vouchers and VA’s homelessness programs.

More Information

- For more information and updates on VA’s programs and supportive services available to Veterans experiencing or at risk of homelessness, visit https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/for_homeless_veterans.asp.

- For more stories like this one, subscribe to receive HPO’s monthly newsletter by clicking here.

- Veterans who are homeless or at risk of homelessness should contact the National Call Center for Homeless Veterans at 877-4AID-VET (877-424-3838).

Monica Diaz is the executive director of the VHA Homeless Programs Office.

Topics in this story

More Stories

William Snow, senior program specialist at HUD, explains how the Point-in-Time Count provides valuable data on Veteran homelessness.

VA permanently housed 47,925 homeless Veterans in fiscal year 2024, exceeding its goals for the third year in a row.

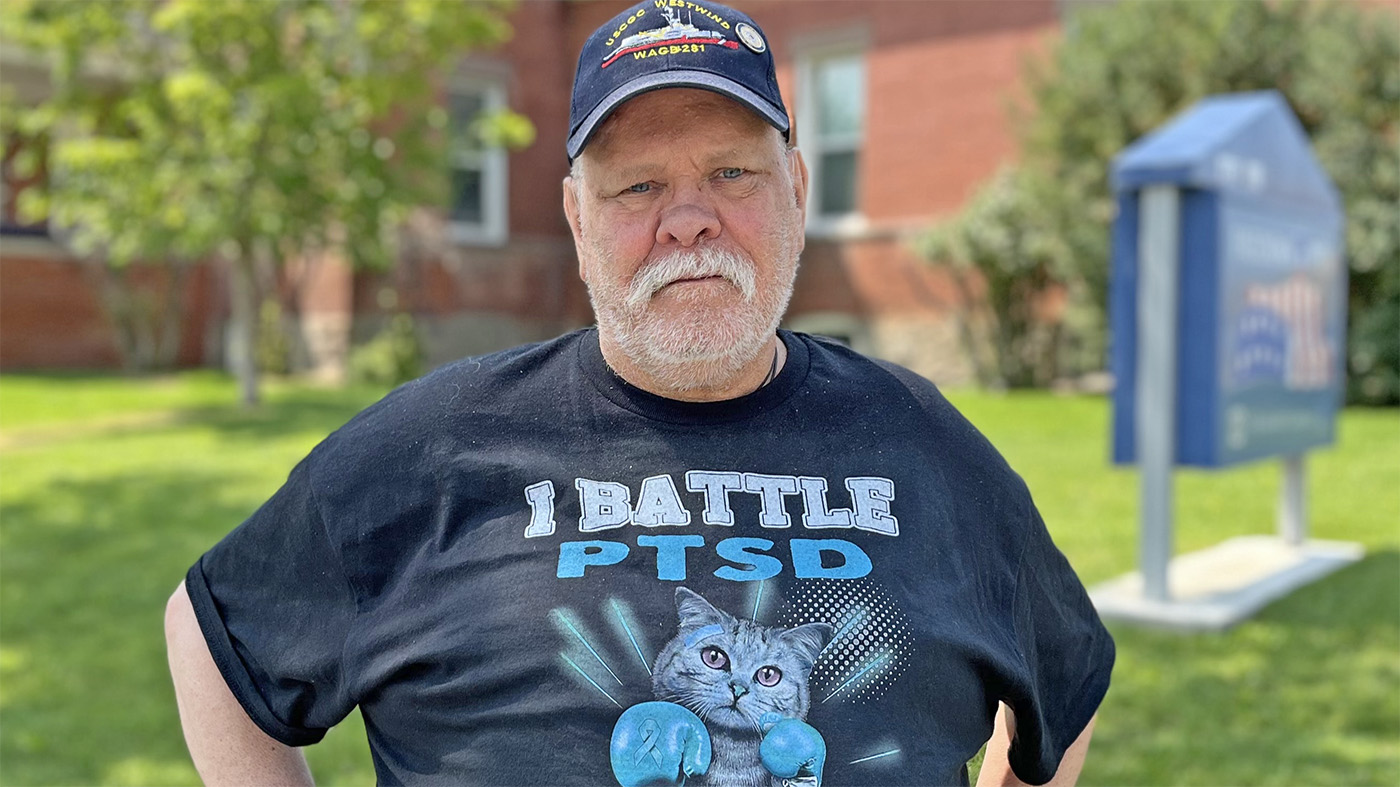

VA Housing First changed the life of Grady Kendall, Coast Guard Veteran, because it was there when life knocked him down.

It’s a shame that a man this great name is with the worse Va Hospital in the country. Literally. This Hospital has the most Veteran COVID deaths. Just a shame. I’m surprised they are still open, for now. I don’t even think they have any black directors. 99 percent of the Veterans that go here are African American. But none of the main leaders are African American. So many deaths because so many people just don’t care because the people that are dead, don’t look like them. White Supremacy is Alive and well at Jesse Brown Va.