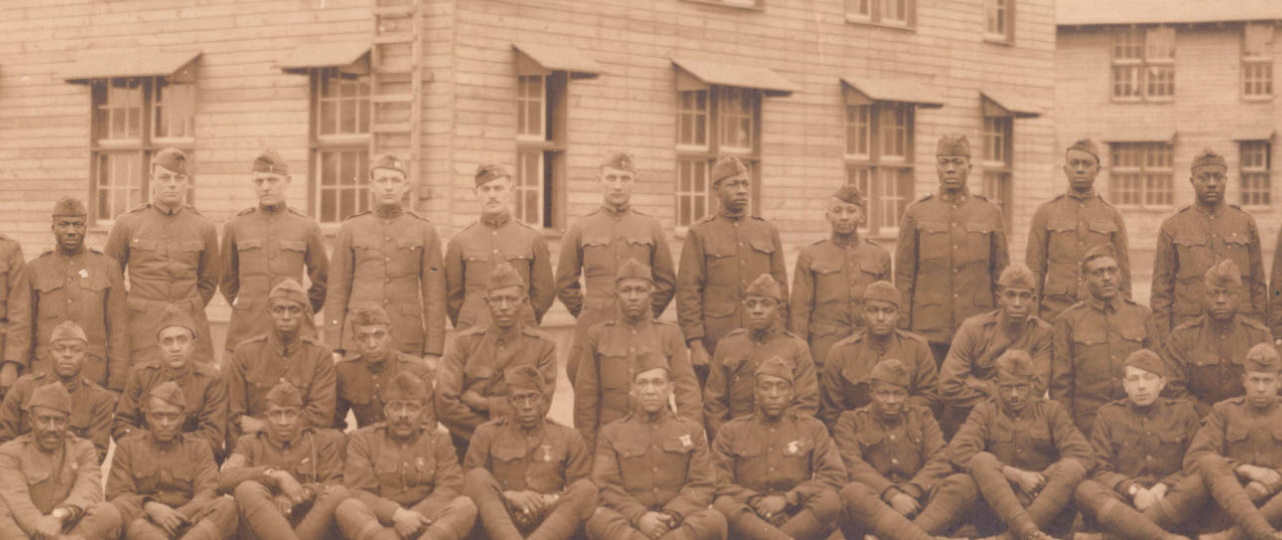

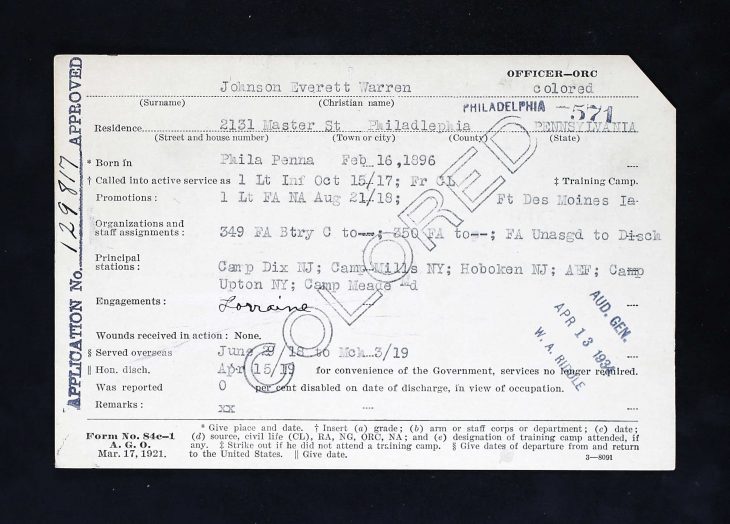

This series of blogs profiles the World War I service and post-war experiences of three Veterans of the 92nd Division’s 349th Field Artillery Regiment, one of the Army’s first predominately African-American artillery units. Alabaman and Colonel Dan T. Moore was its reluctant white commander. First Lieutenant Everett Johnson, a Black officer, commanded Battery E, and Sergeant Robert Samuel Chase was one of Johnson’s non-commissioned officers. All three survived the war and are interred in national cemeteries maintained by VA’s National Cemetery Administration. Both Johnson and Chase, highly skilled and educated, faced their own challenges after the war.

By the time the United States entered World War I in April 1917, African Americans had served in past conflicts and proved themselves equal to white counterparts on the battlefield when given the opportunity. Military service did not overcome racial bias in a Jim Crow society. Prohibited from being Marines, segregated in the Army, and limited to service positions like mess stewards or stevedores in the Navy, they nonetheless filled the ranks of the U.S. military in World War I as both volunteers and draftees.

While most Black soldiers were organized into non-combat units that served behind the lines, the sheer numbers of Black soldiers, as well as backlash from the African American community over limited opportunities to serve in combat, compelled the Army to establish two primarily Black infantry divisions for WWI service – the 92nd and 93rd. Both were sent to the Western Front for combat.

Regiments of the 93rd Division, mostly drawn from pre-war National Guard units, arrived first and were put under command of the French Army. Units of this division, such as the 369th Infantry (formerly the 15th New York Infantry, the “Harlem Hellfighters”) faced more combat and captured more renown than units of the 92nd. Soldiers from both divisions built upon the good record of the African Americans who came before them. Though they fought abroad to “make the world safe for democracy,” they returned home to a country that largely failed in protecting democratic ideals for all its citizens.

The 349th Field Artillery belonged to the 92nd Division’s 167th Artillery Brigade – the first in U.S. history composed almost entirely of African Americans and the first one motorized. They arrived in France in June 1918.

Training and the acquisition of tractors delayed assignments though, such that all 167th units served only a few weeks on the front line before the war ended. It moved to the front on October 18, 1919, in the Toul Sector at Pont-a-Mousson and supported several important infantry raids. It then supported the advance of the Second Army in its drive toward Metz from November 10-11, 1918.

General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), recognized the brigade’s “meritorious” performance: “You men acted like Veterans, never failing to reach your objective.”

Men of the 349th further distinguished themselves with the French population in towns where they billeted after fighting ended. The assistant mayor of Montmorillion wrote to the 349th’s commander, Colonel Dan Moore, upon their departure with his hope that “the white troops replacing your regiment will give us equal satisfaction; but whatever their attitude may be, they cannot surpass your 349th Field Artillery.”

The next installment will focus on Colonel Moore.

Richard Hulver is a historian at VA’s National Cemetery Administration.

Topics in this story

More Stories

This year marked the 75th year of the 2024 Gravois Trail Memorial Day Good Turn Boy Scout flag placing at every gravesite at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

NCA's Cemetery Restoration Project educates communities about private cemetery owners and the caretakers who honor and memorialize Veterans buried without headstones. The restoration project also restores these private resting places to reflect the dignity and honor these Veterans deserve for their service and sacrifice to our nation.

Rubber Tramp Rendezvous is held annually in January, and it provides an opportunity for those who live a mobile lifestyle—in vehicles such as vans, RVs, and buses—to learn more about the benefits and support available to them.