In this second guest blog post, Harvard Extension School Lecturer Cynthia A. Meyersburg, Ph.D., guides student Veterans on how to prepare for and succeed when returning to an academic school. This post examines what student Vets need to accomplish to achieve academic success. Read part 1 here.

Use your organizational skills to prepare for success. Make sure you have the supplies that you are likely to need, such as printer paper, a stapler with extra staples and spare ink cartridges for your printer. If you are attending in person, prepare a kit to bring to and from campus. Include items you are likely to need, such as a computer, ac adapter, phone and a charger, pens, pencils, change, a water bottle and some protein bars. Put together your kit with what would be helpful to you.

Before the semester begins, plan where you can study and do other academic work. or some students, the library is a good option. Others prefer having a designated place at home. For some, a café or coffee shop works well, too.

Have a plan for how to organize information. Use a calendar-planner. Save electronic versions of syllabi and your written work. Save your work in such a way that you will not lose it even if your computer malfunctions (e.g., email a copy to yourself, or store your work in the cloud using Dropbox, Google Drive, etc.). Create folders, both for hard copies of items as well as for files on your computer. Organizing emails into folders can save you time. Designate a place (preferably a single file box or file cabinet) for any important paperwork: Future you does not want to have to spend time looking for your social security card.

Keep track of your priorities and goals. Maintaining a To Do list can be very helpful. Some people prefer to make a handwritten list (people are more likely to remember something they have handwritten rather than something they have typed); others prefer to use a smartphone app or to keep a list on a computer. One strategy that can be helpful is to divide your To Do list into sections: immediate action; short term goals; and long term goals. For any large task, break the task down into small, manageable steps (the smaller the steps, the better).

Choosing a schedule

Programs differ in terms of what courses must be completed in order to fulfill requirements. Meet with an academic advisor at your school so that you know what courses you will need to complete in order to fulfill the requirements for graduation. You will want to know, in writing, what the requirements are. Many schools list program requirements online. If you think you may be interested in graduate school, find out what courses and other experience you will need in order to be a competitive applicant for graduate programs.

If possible, take just one or two courses during your first term (or even two terms). If you are not yet sure of your specific career goals, enroll in classes that interest you. Choose courses that you would look forward to attending.

Gather information about classes and professors. Ask your academic advisor if there are any courses or instructors she or he especially recommends. Ask other students about courses and instructors. There also are public websites that provide student-based information regarding academic courses and professors.

If more than one class is an option to fulfill a requirement, consider which one interests you more. Also, would one better prepare you for classes you will need to take later? Are there prerequisites you must complete? Consider class assignments: If you are more comfortable taking a class with a final paper than taking one with a multiple choice final exam, that may be a factor in making your decision about which class. (However, sometimes you likely will have to take classes that include requirements that are not your preferred type of assessment.)

Some professors are better teachers than others, or may be a better fit for your learning needs. Find out if more than one professor teaches the class or classes you are considering. Sometimes you have a choice, and other times you do not. Planning ahead is a good idea. You may be better off taking a course from a highly respected, well-liked professor this semester rather than having to take it from an unknown professor next year when the highly respected, well-liked professor is away on sabbatical.

When choosing classes, try to balance your schedule so that you have at least one class that plays to your strengths and no more than one class that you are concerned will be a struggle for you. In other words, play to your strengths, but also build knowledge and skills in areas where you could benefit from gaining strength.

If possible, each semester, register for one more course than you plan to take. This way, you can attend the first week of each course, then decide which course to drop from your schedule. If you decide to use this strategy, make certain you know when is the last day you can drop a course without having to pay for it.

Office of Career Services

Meet with a counselor in your school’s Office of Career Services. Ask the career counselor about what coursework and skills employers in your chosen field value. Discuss ways to make yourself more marketable. Inquire about internship opportunities. Ask for help improving your resume, or get help creating a resume if you don’t already have one! (If you also want to read about how to create or improve your resume, I recommend Anne S. Headley’s book, Reflections on Resumes: Taking a Second Look.

Set Aside Enough Time for Academic Work

Expect to spend three hours of reading, writing, studying or other academic work for every one hour of lecture. So, for instance, if you spend 10 hours per week in classes, expect to spend another 30 hours per week on academic work. Allocate time in your schedule so you can complete your academic commitments. Some students with challenges may need to allocate additional time. Good planning and careful time management throughout the term will help you to be less stressed and more academically successful.

Attendance

Even if attendance is not mandatory, behave as if it is. If you are in a large lecture class, make a point of introducing yourself to your professor. Say a quick hello when you walk into the classroom before lecture begins. If it’s an online course, set up a time to meet with your professor. Attend office hours, whether they are virtual or in-person. You want your professor to know who you are, because if your professor knows who you are, that you attend, pay attention and are committed to learning, then if you need extra help, or are on the borderline between two grades, or if an opportunity arises, your professor is more likely to want to help you.

Interacting with Professors

Unless an instructor requests that you use her or his first name, do not address your instructor by first name. Do not use Mr., Miss., Ms., or Mrs. as the title. Unless the professor requests that you use a different title, such as Dr., use Professor. If the instructor has invited the class to use his or her first name, still use the title Professor (e.g., “Dear Professor Jane”) in any written communications.

If you are emailing an instructor, be careful to write an email that conveys respect. Avoid informal language, such as abbreviations used in texting or in other informal communication. Proofread your emails before sending them.

Here is a model e-mail to an instructor:

Dear Professor Grant:

I just enrolled in your Conversational Spanish (Spanish 110) course on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 10 am. I am very excited about the class. I am majoring in education and I think learning Spanish will allow me to help more students. (Also, I am fascinated by Machu Picchu and hope to travel there someday!)

I wanted to let you know in advance that I may need some help from you in order to be able to succeed in your class. I am a returning Veteran, and as a result of injury that occurred while I was in the service, I have limited vision, so I will need to have extra time on in-class written assignments, and I will need large print on exams and in-class handouts. I have a letter from the campus accessible education office explaining the accommodations I need. I will bring the letter with me to the first day of class.

I apologize for any inconvenience, and I want you to know how much I appreciate your help.

Sincerely,

Parker Kim

If a class has a teaching assistant, you may ask during the first section meeting of the semester, “What title should we use when we e-mail you?” Sometimes teaching assistants already have completed their doctoral degrees, so they may be entitled to the title “Dr.”. If you have not yet asked, and you wish to send an e-mail, then use the title “Dr.”. That way, the teaching assistant can let you know if another title should be used instead. You are unlikely to upset or irk your teaching assistant by using a higher title than she or he currently has, but you run the risk of offending or antagonizing by not using a title to which the teaching assistant is entitled.

During office hours or after class, you may ask your professor, “Are there any specific things I could do to improve my writing?” (or work, or participation). Most professors appreciate being asked, especially by students who then go on to implement the suggestions. If you do not understand a suggestion, ask the professor to please clarify or further explain. What seems crystal clear to the professor may not be clear to you; even the best instructors sometimes communicate unclearly, and the most dedicated students can misunderstand.

How do I get back on track if I start having difficulties?

Get back on track as soon as possible: If you perform poorly on an assignment, especially on the first assignment, either go to your professor’s office hours or make an appointment to meet. Ask what you can do to improve your performance. Let your professor know that you care about learning and about the class.

Minimize the impact of difficulties. If you run into difficulties or extenuating circumstances, let your professor know right away. If you do not let anybody know you are having difficulties, then nobody will know that you could use a helping hand. There are additional people at your school who also can help you. Depending on what difficulty you’re facing, you may wish to meet with the head of the academic department, your academic advisor, the dean of student affairs, a campus clergyperson, or a counselor or other clinician from the campus counseling or wellness center.

Suggested Activities:

- Make a list of people you can call or talk with if you’re having a difficult day, or if you want to share a success or accomplishment. Make contact with someone on your list.

- Make a list of your strengths. If you’re having trouble thinking about your strengths, ask a trusted family member, friend or other support person to help you get started.

Cynthia A. Meyersburg, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the Harvard Extension School in the Division of Continuing Education at Harvard University. She thanks retired Air Force Maj. Christopher Kim and Navy Lt. Melinda Mathis, NC, for their contributions and support.

Topics in this story

More Stories

Soldiers' Angels volunteers provide compassion and dedication to service members, Veterans, caregivers and survivors.

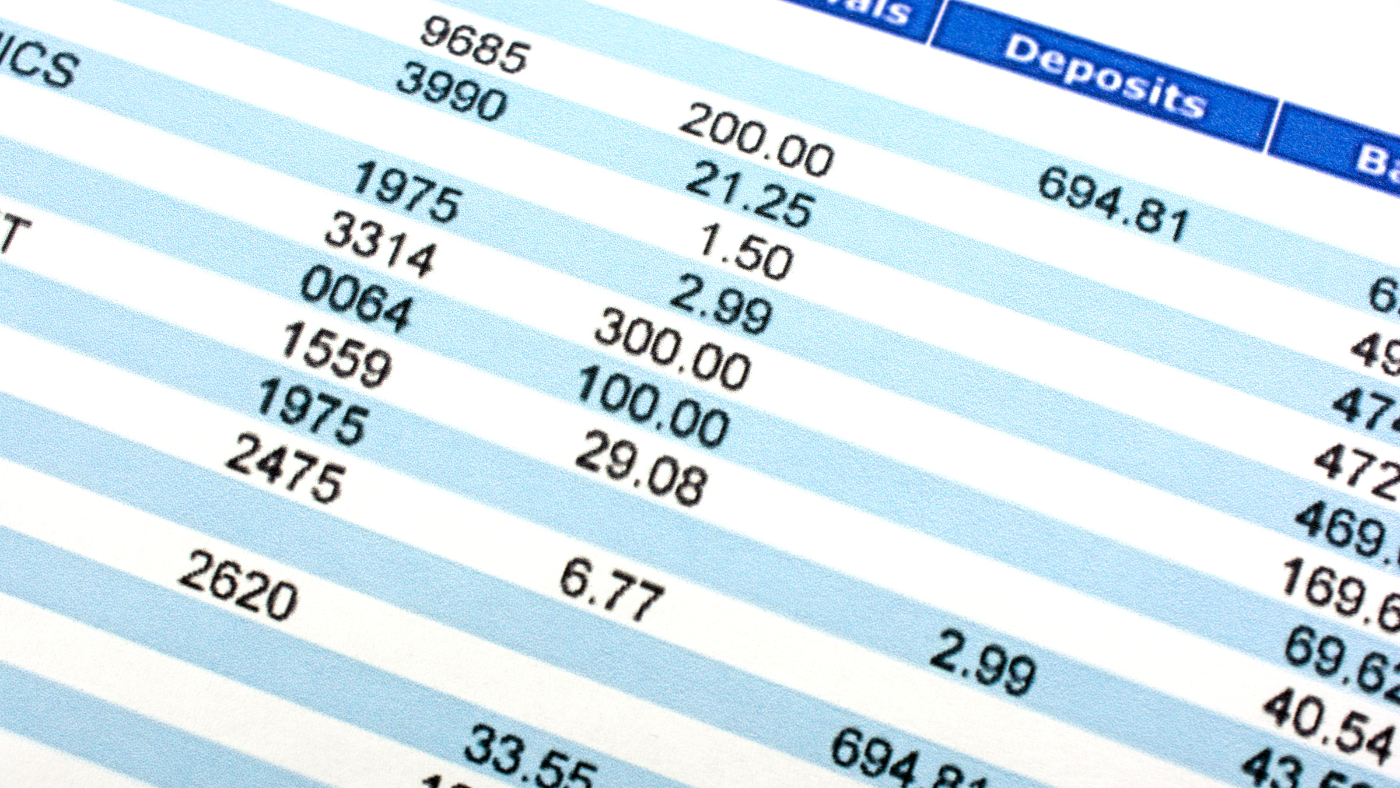

For Veterans especially, the risk of identity theft is high, as criminals target reoccurring monthly benefits payments. Bad actors utilize stolen privacy information to exploit VA benefits, health care and pensions.

Veterans are nearly three times more likely to own a franchise compared to non-Veterans.