Robert Smith, who is legally blind, is a former Marine Corps scout sniper trying to relearn his entire way of life. Smith lost his sight following a stroke in February 2023 while sleeping in his Kansas City, Missouri, home. He is now completing a six-week inpatient program at Edward Hines Jr. VA’s Central Blind Rehabilitation Center.

Today’s lesson is crossing the street by himself. “The first time I tried this on my own, it was terrifying,” the 55-year-old said while navigating a curb. “It’s these little things we take for granted.”

Approximately 130,000 American Veterans are legally blind and over one-million have significantly limited vision according to VA. Like Smith (pictured above), thousands are referred to one of 13 VA Blind Rehabilitation Centers annually.

Hines VA’s center is VA’s oldest, founded 75 years ago by Russell C. Williams. Soon after landing on the beaches of Normandy in 1944, he was blinded during a German artillery attack.

After rehabilitation and instructing at the Army’s now-closed blind treatment center in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, Williams was selected to serve as the Hines center’s first chief. He believed that a visually impaired person could continue an independent life by combining new and old medical practices and training techniques to treat a person’s whole health.

Veteran says pioneering approach saved his life

Seventy-five years later, Smith credits this pioneering approach with saving his life.

“Overnight, I lost everything. I lost my vision. I lost the way I supported myself. I woke up and it was all just gone,” Smith said. Feeling helpless, he attempted suicide in March 2023.

“I think a lot of Vets out there who have lost their sight, especially if they recently lost it, probably experience the same thing. I know they feel like things are out of control and they don’t know how to fix it,” he said.

For several months, Smith’s visual impairment service team coordinator from Kansas City VA called him to get him enrolled in the Hines program, but he refused. “Finally, just to get her to quit calling, I said, ‘Yes, I will go,’” Smith said.

Smith arrived on May 23 but didn’t expect his life to change. He said he spent the first two weeks arguing with his instructors until his second weekend when staff took him to a shooting range. An avid marksman, he shot 25 out of 30 bullseyes in his first attempt using assistance devices that play sound to help the visually impaired sight a weapon.

“Not just the target, the bullseye,” he said, smiling. “That was the beginning of me realizing that my life can go on.”

Smith’s initial hesitation is not uncommon according to Anthony Cleveland, orientation and mobility supervisor. “We see a lot of people come in through the admission process really unsure of what we can do for them and what’s left for them to do?” Cleveland asked.

Maggie Elgersma, the center’s chief, who has worked at the center for 14 years, described the importance of teaching Veterans to continue their passions after losing vision: “It’s a huge motivator toward goals and remaining independent after vision loss and reintegrating into their community.”

Skills now common in modern blind rehabilitation

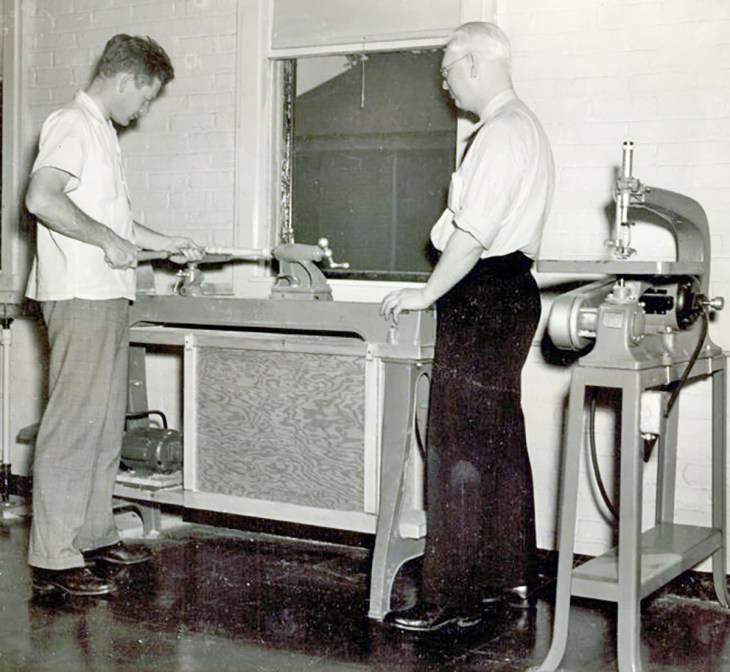

The photo at right shows Veteran Naron Ferguson learning woodworking at the Hines Blind Rehabilitation Center. Ferguson became the first trainee at the center in July 1948 after losing his vision when injured during World War II.

Other early photographs show Hines patients learning skills now common in modern blind rehabilitation, including woodworking, cooking, golfing and walking in the community.

Patients also learned to use a long white cane to scan their environment, the center’s most well-known contribution to visual impairment rehabilitation.

The canes were still new and considered a novelty items by many. Early designs were difficult to use. Williams and his team modified the long cane into the tool used today, and their methods included sizing to each person, using a plastic tip for sensitivity and including a grip for better control in any weather. They also improved navigating techniques and using sound to understand their surroundings, leveraging their real-world experiences to build a new curriculum.

Today, millions of people worldwide have used the long white cane—including Smith, who practiced different cane techniques while walking through Hines VA. “Before coming here, my only reference to using a cane was from watching Al Pacino in ‘Scent of a Woman,’” Smith joked while showing different methods he learned at Hines.

The cane is only one part of rehabilitation for Smith and the more than 10,000 Veterans who have stayed at the Hines center since 1948.

Focus on rehabilitation programs tailored to each Veteran’s needs

Hines opened its new Central Blind Rehabilitation Center in 2005, replacing the old World War II-era buildings with a modern facility able to treat up to 34 patients for four-to-six-week programs with the help of about 50 staff.

The modern facility focuses on five rehabilitation programs tailored to each Veteran’s needs: Living skills, computer access training, visual skills, manual skills, and mobility and orientation.

Smith moved to one of two apartments in the rehabilitation center toward the end of his stay to better his independent living. While in the apartments, Veterans are responsible for all their day-to-day needs, including cooking and cleaning. “It’s kind of a trial run to see how they’d do if they’re trying to get their own apartment or move out on their own,” said Sarah Milledge, blind rehabilitation specialist.

Veterans also learn how to operate specific technology to aid their needs, such as assisted reading devices, braille reading and writing aids, voice-activated technology and GPS devices. Once a Veteran finds a device that works, they take it home for free.

Smith mentioned his difficulties writing in braille and was quickly shown an aid. He counts learning to play the guitar and crafting his own leather guitar strap in manual skills training as a personal triumph during the program. “It’s something I always wanted to learn, but I always thought my fingers were too short.”

More confident and capable when they return home

According to Ernest Staines, blind rehabilitation specialist for manual skills, learning skills like playing the guitar hold deeper meanings: “It’s something that helps them to be more confident and capable in their daily independence while they’re here and once they return home.”

Smith graduated on July 14 and planned to golf with his brother for the first time since losing his vision. “I think once he learned what we had to offer, he really embraced the program and what he could gain from it. He really thrived,” said Elgersma. “Mr. Smith is a success story of what we do at the blind center and why we do what we continue to do after 75 years.”

Veterans can be referred to any of the VA’s 13 centers by contacting a visual impairment service team coordinator available at every VA medical center or through a VA eye clinic for low-vision Veterans.

Topics in this story

More Stories

Moving the body in gentle ways is good for you, and with this practice, you don’t even have to get out of your chair!

Take the Five Days to be Healthier Together challenge to be stronger and healthier.

VA is putting Veterans in the driver's seat for making medical appointments.

Greta article. Looking forward to sharing with my veteran clients. My only regret was seeing that the long cane technique, created by Dr Hoover and still called The Hoover Technique was not credited.

This is an excellent article. I lost most of my vision in 2013,

during back surgery, when I had a stroke.

I am fortunate to have family and friends support. It was very difficult at first,

but the eye clinic at West Palm Beach, has supported me with resources, that let me

continue as a security consultant. 80 years old and still going.