Bobby Grier’s team, the University of Pittsburgh Panthers, were closing out a very successful 1955 season ranked 11th in the country. They were invited to the 1956 Sugar Bowl in New Orleans against seventh-ranked Georgia Tech, a national juggernaut.

Back in the era of the two-way player, Grier logged time at both fullback and linebacker. He had an up-and-down career at Pitt. But the Massillon, Ohio, native could think of nothing better than to end his collegiate playing days with a victory over one of the country’s best teams in arguably the nation’s preeminent bowl game.

Grier didn’t consider the fact that he was about to make history becoming the first Black athlete to play in the Sugar Bowl. There was one problem, however.

Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin was determined to keep Georgia Tech off the field. He proposed that either Grier does not play, or Georgia Tech withdraw from the Sugar Bowl.

University president: “He plays or I resign.”

Georgia Tech players supported Grier. Their university president, Blake Van Leer, threatened to resign if his team wasn’t allowed to suit up against Grier and the Panthers.

Students at both Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia protested the governor’s decision, even burning him in effigy on the Georgia Tech campus. In the Pitt locker room, teammates said they would not go to New Orleans without Grier. “No Grier, no game,” was their slogan.

As the Sugar Bowl approached and controversy swirled all around him, Grier chose to focus on the game. “I wasn’t worried that I wouldn’t be able to play,” he said.

In 1955, Grier was the only Black player on Pitt’s roster. In New Orleans, Grier’s teammates stayed in the dorms at Tulane University. Due to segregation laws, Grier had to stay at Dillard University, a historically black institution near Tulane.

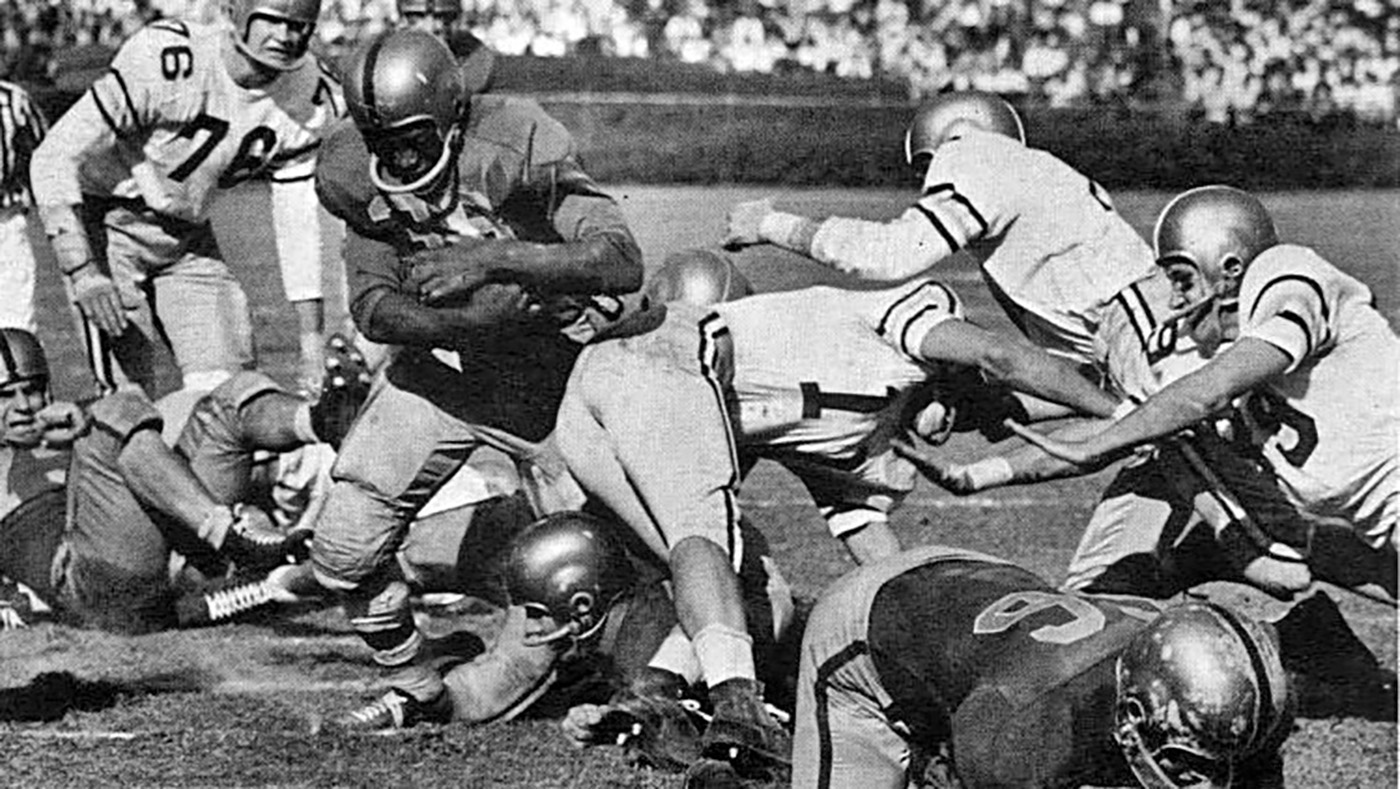

Grier played a pivotal role in the game. On offense, he led both teams with 51 rushing yards (pictured above) breaking free on a couple of long runs. Defensively, he was called for pass interference in the end zone and it set up Georgia Tech for its only touchdown of the game.

Referee admitted botched call

The Yellow Jackets won 7-0. Several decades later, Grier maintains he did nothing wrong and the referee who threw the penalty flag eventually admitted it was a botched call. “I never shoved that guy,” he recalled, of the play.

In the locker room, Grier sobbed in frustration over the heartbreaking loss and the blown call. But he had no qualms about how Georgia Tech played, hard-fought and respectable. “There were no cheap shots when they tackled me.”

Following the game, both teams were invited to a dance and dinner banquet at New Orleans’ St. Charles Hotel, which served white patrons only. But as the Panthers made their way to the hotel, a group of about five Georgia Tech players—all from the South—met Grier as he walked off the team bus. “You’re eating with us,” they told him.

Walking into the banquet hall, Grier received the loudest ovation of any player in the Sugar Bowl. “That made me feel good. Made me feel special,” he said. He’s been inducted into the Sugar Bowl Hall of Fame and the Pitt Hall of Fame.

After that, Grier pursued another dream… flying. He graduated from Pitt, married his college sweetheart, Dorothy, and joined the Air Force in 1957. He got to fly some but spent most of his military career working on radar and missiles. Grier spent more than 12 years in the service and left as a captain.

Post Air Force, Grier, then a father of two, worked as a supervisor for US Steel and then as head of maintenance for Community College of Allegheny County North for 28 years.

In recent years, Grier has served the Dole Foundation to help provide caregiving for Veterans. His advice for life? “Have a lot of patience. And just let the players play.”

Topics in this story

Link Disclaimer

This page includes links to other websites outside our control and jurisdiction. VA is not responsible for the privacy practices or the content of non-VA Web sites. We encourage you to review the privacy policy or terms and conditions of those sites to fully understand what information is collected and how it is used.

More Stories

Bob Jesse Award celebrates the achievements of a VA employee and a team or department that exemplifies innovative practices within VA.

The Medical Foster Home program offers Veterans an alternative to nursing homes.

VA joined the Congressional Hispanic Caucus at a roundtable event to discuss the challenges faced by Hispanic Veterans and military families.