This post from the VA Center for Innovation originally appeared on Medium.

Kathryn Havens stands out amid other students taking design courses at Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design (ID). They’re beginning their careers; she works as the Medical Director of the Women’s Health Clinic of the Milwaukee VA. She’s neither your typical medical director, nor your typical designer, but she’s made the latter an important part of her career.

“I got really interested in design thinking. I ate up everything I could on it. I spent a lot of time in San Francisco, went to conferences, visited IDEO. Institute of Design is the closest comparative thing nearby. I wanted to learn more so I traded teaching medicine and design thinking for taking some classes.”

Her enthusiasm for design is infectious and her use of it impressive: she brought human-centered design to her clinic and led a team that completely redesigned the way the clinic tests their women Veterans for HIV.

VA screens 87% of Veterans for cholesterol and 68% for high blood sugar. But we only screen 20% for HIV. Nationwide, according to the CDC, 55% of all Americans have never been tested for HIV. Kathryn Havens and her team realized that over the previous three years, they’d only tested three women for HIV, a number they found unacceptably low.

Kathryn might have gone through traditional channels to address the problem. She might have sought out rules that mandated doctors ask about their patients’ sexual histories to determine if they ought to be tested. She could have tried adding an HIV-testing metric to the myriad existing performance measures for VA doctors. Instead, she tried a new approach: human-centered design.

She didn’t want a top-down approach. She wanted to find out from the providers themselves why they ended up conducting so few HIV tests. To do that she called on a few of her “classmates,” design students from ID, to help lead the Discover phase of the human-centered design process. They brought fresh eyes and new questions. Through their interviews, she and the researchers quickly realized a few key insights.

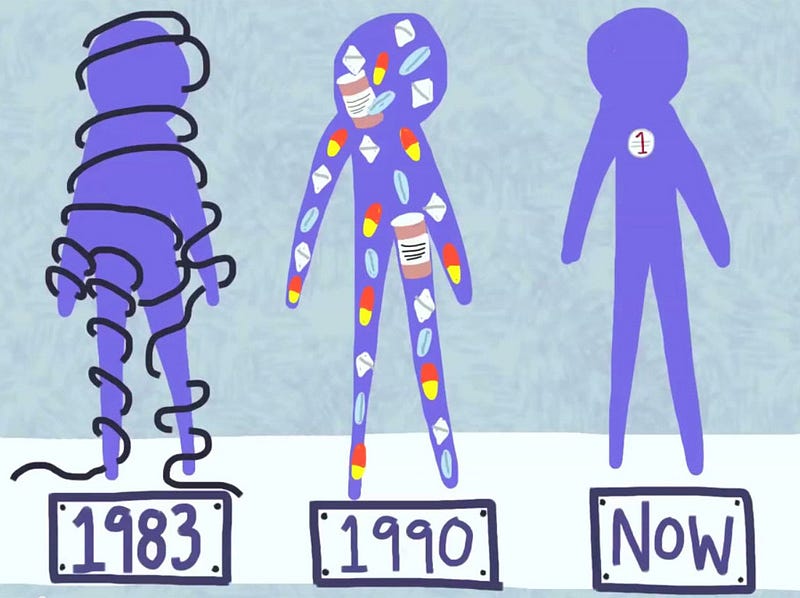

First, Kathryn and her team identified that their facility needed to reeducate themselves on HIV.

Most providers, the students noticed, were in their mid- to late-fifties. They had developed their formative understanding of HIV during their residencies, at a time when doctors first began to grapple with HIV. Then, HIV killed quickly and terribly. The era that followed saw HIV managed with dozens of drugs causing terrible side effects. Today, however, treating HIV has changed dramatically. If a test catches HIV early enough it can be managed on one pill a day with minimal side effects. It’s now more akin to a chronic disease than a quick-killing virus. People with HIV now generally live longer than those who smoke and early treatment can reduce the risk of transmitting HIV to other by 96%.

Second, the research team identified why doctors ordered so few HIV tests.

Answer: they often don’t know which of their patients should even be tested.

To understand a patient’s likelihood of contracting HIV you need to go over their sexual history and any history of drug use. Many doctors dread that conversation, both for its length — doctors are busy, the research team found out — and its subject matter. And they admitted that in conversations to Kathryn’s team.

With these two key insights gleaned from the Discover phase, the team ideated potential solutions.

To better understand HIV, the clinic partnered with AIDS advocates in the community. “We brought experts into the facility to talk about HIV in the community,” Kathryn explained. “That allowed [our staff] to ask questions and answer their own fears about HIV. It allowed them to get up to their own capacity and get information.”

To increase the number of tests the Clinic ordered, the design students realized the solution didn’t lie with the doctors. They wondered, instead, why the test couldn’t just be ordered like any other?

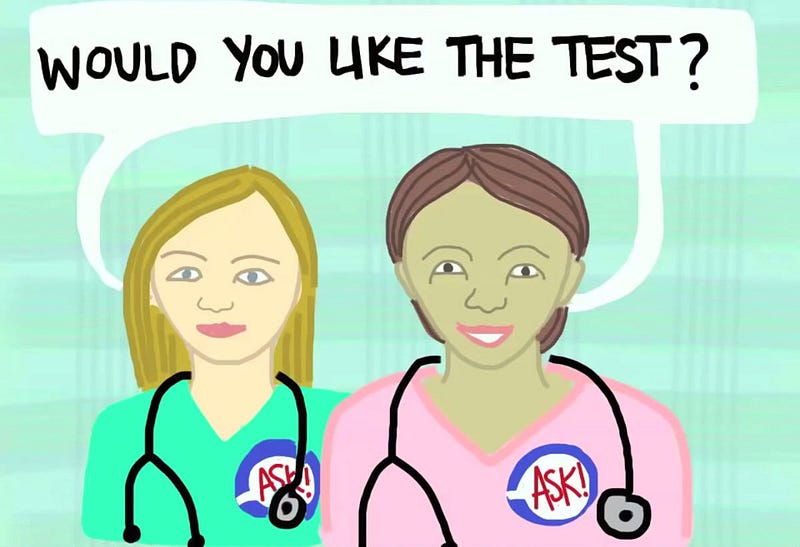

At the start of a doctor’s visit, patients usually see a licensed practical nurse, or LPN. An LPN provides that basic bedside care we’re all familiar with: weighing, measuring, and taking your blood pressure. They also often collect samples for testing. Why couldn’t they also ask about an HIV test at this point? Turns out that they can.

Instead of diving into a conversation about the details pertaining to sexual history, the team put into place a system where the LPNs simply ask, “Do you want the test?” If yes, then the LPN would alert the provider to order the test.

“We don’t [initially] go into their sexual history or ask ‘do you do drugs?’” Kathryn explained. “We simply ask ‘Do you want the test?’” The longer conversation comes later.

Women overwhelmingly did. In just three months, the Center tested over 400 women. Their prototype clearly worked.

This is the simple power of HCD: squashing assumptions and having honest conversations. When asked what her team did right, Kathryn responded: “The ID students saw so many things that we never saw. They identified that the problem was the fifteen minute review of all the questions before even ordering the test. We didn’t know that; we just didn’t know that was part of the problem. We were able to trust the members of our team to be able to ask that question.”

But, as Kathryn says, “you can’t ask a question if you aren’t prepared to give the answer.” The team educated themselves on HIV, but they still needed determine how to educate and begin care for the Veterans who tested HIV positive.

They extended an approach that has already brought them success. VA has embraced wrap-around care through the use of Patient-Aligned Care Teams (PACT teams). These teams put Veterans at the center of holistic care by including the primary care provider, nurse, clinical associate, administrative clerk, and specialists. To stay true to that philosophy, Kathryn and her team couldn’t just send Veterans over to the Infectious Disease Department; instead, they now conduct “warm handoffs”.

“We’d sit with the women and walk through all the information with them.”

So now, if a Veteran tests positive for HIV, she comes in to meet with her primary team and the infectious disease nurse. Tests are drawn, questions are asked, and answers are provided.

Kathryn’s proud of what this improved process brought the Veterans she serves: peace of mind, education, and, if necessary, better, faster treatment.

“This was my first project using design thinking,” Kathryn said. “I come from a background of a researcher, where [when you have a problem] you get funding four years later and by that time it’s irrelevant.” HCD is different, she notes. “I love the iteration and that you can keep changing how it works.”

Kathryn and her team found simple solutions to a serious problem in a quick timespan. They improved patient care. Importantly, they want to make it possible for others to do the same. Their program represents a prototype that worked, and Kathryn wants to see it taken to scale.

“For me,” Kathryn emphasized, “what’s important with design thinking is that if you can learn how to do something then you diffuse the information. If we can’t do the research and diffuse it, then that’s an inefficient use of research and resources.”

To do that, they made an instructional video. (Watch it below) Other Women’s Health Clinics in their area have begun to follow their process already.

As she says in the video, “The best part of this story is that your PACT team can do it too. Make it simple. Just ask:

‘Do you want an HIV test today?’

Dr. Kathryn Havens is an Associate Professor of Internal Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the Director of Women’s Health at the Milwaukee Zablocki VA. At VA, she is working with team members to create human-centered design programs to improve the care of patients. In addition to the story above, she has developed several innovative programs based on the needs of women including cardiac, pre-diabetes lifestyle intervention programs, and a multi-disciplinary behavioral health program for women with diabetes. Additionally, she has taught at the Illinois Institute of Technology Institute of Design as well as participated in classes to develop her own understanding of implementation skills for the application in medical settings.

Topics in this story

More Stories

Soldiers' Angels volunteers provide compassion and dedication to service members, Veterans, caregivers and survivors.

Veterans are nearly three times more likely to own a franchise compared to non-Veterans.

The Social Security Administration is hoping to make applying for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) a whole lot easier, announcing it will start offering online, streamlined applications for some applicants.