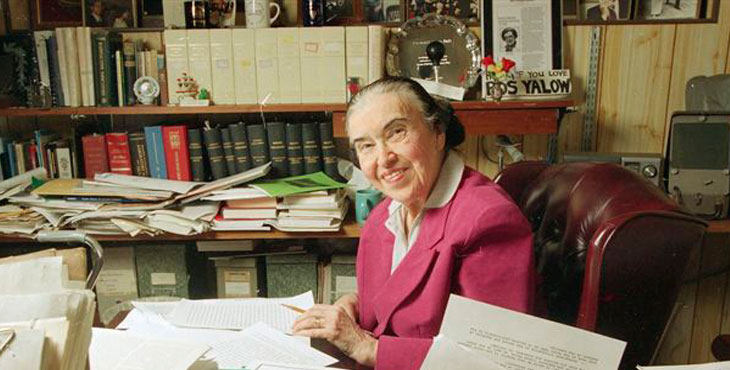

In 1977, Dr. Rosalyn Sussman Yalow, physicist and researcher at the Bronx VA Medical Center, was awarded a Nobel Prize in medicine. Today, she remains the only woman VA doctor to have had that honor.

VA’s Dr. Rosalyn Sussman Yalow, with Dr. Sol Berson, pioneered research that led to a Nobel Prize in medicine.

Rosalyn Yalow became interested in science at the age of 17 when she read a biography of Madame Curie. Like most women, she ran into her share of roadblocks along the way as she pursued her dream of becoming a scientist. She didn’t want merely a career, she wanted to be a wife and mother, too. She was denied opportunities for assistantships in graduate school because of her gender and nepotism, but she never gave up and stayed focused. She once said, “I’m very disciplined. I’ve always put my eye on where I’m going. Trivial things don’t matter to me, and I’m willing to make compromises, except in principle.” Dr. Yalow juggled career, marriage and children, often working 60-80 per week and peeling potatoes for dinner in late meetings.

In the wake of World War II, VA’s Administrator General Omar Bradley made sweeping changes to modernize the agency. In 1946, he established a Department of Medicine and Surgery, medical school affiliation programs, a robust medical research program, and much more. VA’s Radioisotope Service, later named the Nuclear Medicine Department, was created the following year with the intention of attracting the best and brightest scientists to engage in the exciting new research field. The first nuclear reactor was invented by Italian physicist, Enrico Fermi, just a few years earlier in 1942, so it was cutting-edge research and technology at the time. The Bronx VA hospital was selected as a site for nuclear research. Rosalyn Yalow, the second woman to receive a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Illinois, who worked at the Bronx VA as a consultant at the time, was hired for the nuclear research program. In 1950, she was appointed assistant chief of the hospital’s radioisotope service.

She worked with Dr. Solomon “Sol” Berson in the lab since the 1950s and claimed that their discovery of radioimmunoassay was an accident—an off-shoot of another investigation related to adult onset diabetes. Some of their early work in the biology of metabolism showed that animal insulin given to diabetics did, in fact, produce antibodies in humans. They were able to ”tag” insulin in the blood with radioactive iodine–to see and measure it. Their discovery made what was then the immeasurable—the body’s own circulating insulin—measurable: “It was like identifying a teaspoon of sugar in a lake 62 miles long, 62 miles wide and 30 feet deep.”

Dr. Yalow received the Nobel Prize in 1977, five years after Dr. Berson’s death, for the “development of radioimmunoassays of peptide hormones.” Dr. Berson, her long-time colleague, died on April 11, 1972, and probably would have been honored alongside Dr. Yalow, but Nobel Prizes are never given posthumously. Radioimmunoassay (RIA) is a highly sensitive technique for measuring tiny amounts of substances in the blood. Hormones are classified under two groups: steroid hormones and peptide hormones. Insulin, prolactin, and oxytocin are examples of peptide hormones. Dr. Yalow and Dr. Berson’s work led to the discovery that Type 2 diabetics have MORE insulin, not less, in their bodies than non-diabetics, which defied conventional scientific thought of the day. Their discovery became useful in diagnosing hypothyroidism and the testing of Hepatitis B virus.

Dr. Yalow was named to the National Academy of Sciences in 1975 and received the Albert Lasker Award in 1976. When she received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1977, she was the second woman to ever receive the prize. She was awarded half of the $145,000 prize; Dr. Andrew Schally, of the VA hospital in New Orleans, and Dr. Roger Guillemin, of the Salk Institute in San Diego, received the other half for their discoveries concerning peptide hormone production of the brain.

Dr. Yalow never retired. She maintained emeritus status at the Bronx VA Medical Center and Mount Sinai Hospitals until her death on May 30, 2011

About the author: Darlene Richardson serves as a historian for the Veterans Health Administration.

Topics in this story

More Stories

The Medical Foster Home program offers Veterans an alternative to nursing homes.

Watch the Under Secretary for Health and a panel of experts discuss VA Health Connect tele-emergency care.

The 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report provides the foundation for VA’s suicide prevention programs and initiatives.