NCA intern Maari Weiss shares with us today the story of Joseph A. Farinholt (above, on right), who earned four Silver Stars for his gallantry in combat against the enemy during World War II. He earned a Purple Heart, as well. Military historians believe that Mr. Farinholt is the only enlisted servicemember to have earned four Silver Stars. But what elevates this extraordinary heroism even further is what he did with his own post-War legacy.

Mr. Farinholt is interred at Garrison Forest Veterans Cemetery, a Veterans cemetery built by a grant from NCA and managed by the Maryland State Department of Veterans Affairs. In addition to managing VA’s 135 national cemeteries, NCA also works with state and tribal governments to build veterans cemeteries through our grant program. There are 105 state and tribal Veteran cemeteries built with NCA grants, and they all enshrine American Veterans’ Legacy. For what he did in his time in uniform and for what he did afterward, Mr. Farinholt’s Legacy is one we are pleased to honor.

Like Jerry Yellin, Mr. Farinholt felt compelled to share his experience in a positive way, to connect with younger people who were interested in history or military service. When he traveled to Bosnia to visit U.S. troops serving in the peacekeeping mission there, he simply wanted those soldiers to understand that there were people back home who supported them and understood what it was like to serve overseas as a young adult.

Or perhaps even younger.

Please enjoy Maari’s Veteran Spoltlight of Mr. Farinholt.

Joseph A. Farinholt was one of America’s more highly decorated soldiers of World War II, earning four Silver Stars and a Purple Heart, among other honors. In Mr. Farinholt’s short memoir, he modestly tried to explain away his heroics, saying “I was a flip kid to begin with and I didn’t think that I was going to survive the war anyway, so I made up my mind that … I was going to do everything I could to help win.” The Library of Congress has digitized the entire Veterans History Project collection devoted to Mr. Farinholt, and it can be accessed online.

Mr. Farinholt was born in Catonsville, Maryland, to Frank and Mildred Farinholt, “the seventh of 11 children and the fifth of seven boys.” He remembered that “for all of us it was a tremendously happy childhood.” The kids “never realized during the Depression that [their] family didn’t have much money.” Mr. Farinholt slept in the same bed as his brothers until he dropped out of Catonsville High School to work and live on his uncle’s farm in Baltimore County. He “wanted [his] own bed, money for food and clothes and … to help [his] family.” Before long, however, Mr. Farinholt decided that “[a]lthough [he] was only 15, … perhaps the Army would be the ticket for [him], because it could provide all that [he] wanted: [his] own bed, food, clothes, and money.”

When Mr. Farinholt went to Baltimore to put his plan into action, he lied to an Army recruiter, claiming to be 16. However, the recruiter did not believe him and sent him home, where his uncle declared that “‘if you’ve got to lie, you tell a big lie. Don’t you tell a little lie, because people don’t believe little lies.’” With this in mind, Mr. Farinholt went back to Baltimore, told a National Guard recruiter that he was 23 years old, and successfully enlisted. He liked it immediately and made lifelong friends.

After about two years in the National Guard, “[i]n October 1940, the company asked some of [them] to come on to active duty early, so [Mr. Farinholt] volunteered and … helped get the unit ready for war, mostly by doing a lot of administrative things.” He later trained at Fort Meade and deployed to several different places during training.

Just before he was supposed to leave Camp Kilmer, New Jersey for England, Mr. Farinholt found out that his younger brother, Paul, had been in an accident and was in a coma. Unable to get a pass due to his imminent departure, Mr. Farinholt “went AWOL (Absent Without Leave) and headed straight home.” However, upon his arrival, his mother “angrily ordered [him] back to Camp Kilmer. … She was extremely strong, and although [Mr. Farinholt] hated to leave her and the family, [he] went back to Camp Kilmer.” His buddies had packed his bags for him, and he dashed off to make his ship.

Mr. Farinholt arrived in England after “about ten days” on the Atlantic Ocean, and was greeted by German bombs. He then went to work, preparing for D-Day without being explicitly informed about the end goal of his training. However, he thought that they were going to be involved in an important event, because they “participated in a number of amphibious exercises and a great number of important visitors came to observe [their] training. … [They] didn’t know for sure, but [they] all figured that [they] would be part of the initial assault in Europe.”

Joe Farinholt, with his uniforms and equipment laid out for inspection in the period before D-Day, 1944. Tidworth Barracks, England.

Mr. Farinholt earned his first Silver Star while fighting in hedgerow country in July 1944. He recalled that he “wasn’t looking for medals, but the whole experience made [him] feel less afraid of everything.” Less than a week later, he earned his second Silver Star, noting that the men who joined him on the raids that led to the award were instrumental in their success. Throughout the war, Mr. Farinholt often relied on his humor, and his experience at the ceremony in which he was presented with his second Silver Star is no exception. After being “in combat for more than three straight months, [his unit] moved to the rear for a rest,” and Mr. Farinholt was told to get cleaned up for an awards ceremony. However, he did not remember to shave, and, when General Eisenhower reached Mr. Farinholt in the line of soldiers, he asked Mr. Farinholt “‘How long has it been since you shaved?’” Mr. Farinholt responded, “‘I’m sorry, sir. I haven’t got time to shave and win this … war at the same time.’” At this, “General Eisenhower just smiled and laughed and went on down the line.”

Joe Farinholt (right) posing with fellow platoon members Bill Stamos (center) and Stephen McNeil (left). While under Farinholt’s command at Bourheim, Germany, Stamos was one of four others in the platoon to earn Silver Stars. Stamos received it for actions performed on November 23, 1944.

Having already earned three Silver Stars, Mr. Farinholt continued to show extreme courage on the battlefield, culminating in a lifelong injury and a fourth Silver Star. On November 26, 1944, he and his platoon were fighting in Bourheim, Germany. After a blast killed Private Thomas Victor, the man who operated the gun that “was in the best position to stop the Germans,” Mr. Farinholt “ran to it” and managed to hit the “tank that was leading the [German] column.” However, the tank returned fire, and Mr. Farinholt “was hit several times in the exchange. … [His] lower leg was shattered … and [he] had five bullet wounds in [his] thighs and two in [his] back.” Rather than “wait[ing] for a medic,” Mr. Farinholt crawled and drove to tell his commanding officer that the Germans were coming and to get medical attention. His leg was so badly injured that he couldn’t really work the car and had to crash it into the Command Post house to get it to stop, but he kept refusing medical attention until he could relay his message about the Germans to a commanding officer. He received last rites, but, luckily, the battalion surgeon was able to get him stable enough to be evacuated to the rear.

After his injury forced him off the battlefield, Mr. Farinholt “was sent to England … and eventually to Woodrow Wilson Army Hospital in Staunton, Virginia. [He] had several surgeries and spent nearly two years there learning how to walk again.” Unfortunately, “[t]he doctors were never able to get the wound in [his] right shin to close completely,” so he “learned how to walk on it … [and] had to change the bandage on it twice a day all of [his] adult life.”

Joe Mr. Farinholt with new bride Agnes ‘Reds’ Farinholt at Woodrow Wilson Army Hospital in Staunton, VA.

While he was still in Woodrow Wilson Army Hospital, Mr. Farinholt married Agnes Marshall, whom he called “Reds” due to her red hair. They raised five children and had several grandchildren. In his memoir, Mr. Farinholt said that “[t]he doctors told me that because of my condition after the war, I shouldn’t have a family. What did they know? … I have a great family. I defied the odds, I guess.”

In his post-military life, Mr. Farinholt had several different occupations; he “farmed, owned a jewelry store and a gas station and auto repair shop. [He] also earned [his] private pilot’s license, owned a semi-pro football team and was active in the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars.” He was “proud” to serve as a volunteer with the 29th Division Association. Additionally, he and his wife went “to schools [to] talk to the kids about the war,” which Mr. Farinholt found rewarding. He went to Bosnia to visit with soldiers on a peacekeeping mission there and was inspired by them. Mr. Farinholt knew that today’s young people face different challenges than his generation, but he believed in them, writing that he “want[s] today’s soldiers to know that we have faith in them.”

Joe Farinholt and his wife “Reds” with Maj. Gen. James F. Fretterd, the Adjutant General of Maryland, and Maj. Drew Sullins, at a ceremony naming The 5th Regiment Armory Drill Hall in his honor on June 1, 2002. Farinholt passed away 10 days later.

Joseph A. Farinholt passed away on June 11, 2002. He reported in his memoir that he “had a great life.” He was laid to rest in Garrison Forest Veterans Cemetery, in Owings Mills, Maryland. We honor his service.

Grave marker of Joe Farinholt, at Garrison Forest Veterans Cemetery, a Maryland State Veterans Cemetery. Photo credit: Maryland Department of Veterans Affairs

Source:

Joseph A. Farinholt (AFC 2001/001/03521), Memoir (MS01), Veterans History Project Collection, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.

Topics in this story

More Stories

In November 2024, VA's National Cemetery Administration (NCA) officially opened new Green Burial sections at three national cemeteries.

Beginning on Nov. 9, 2024, VA will accept applications for payment of a monetary allowance for privately purchased OBRs and for OBRs provided by a grant-funded cemetery, when the OBR is placed at the time of interment. This allowance may be paid for burials that occurred on or after the effective date of the new authority which is Jan. 5, 2023.

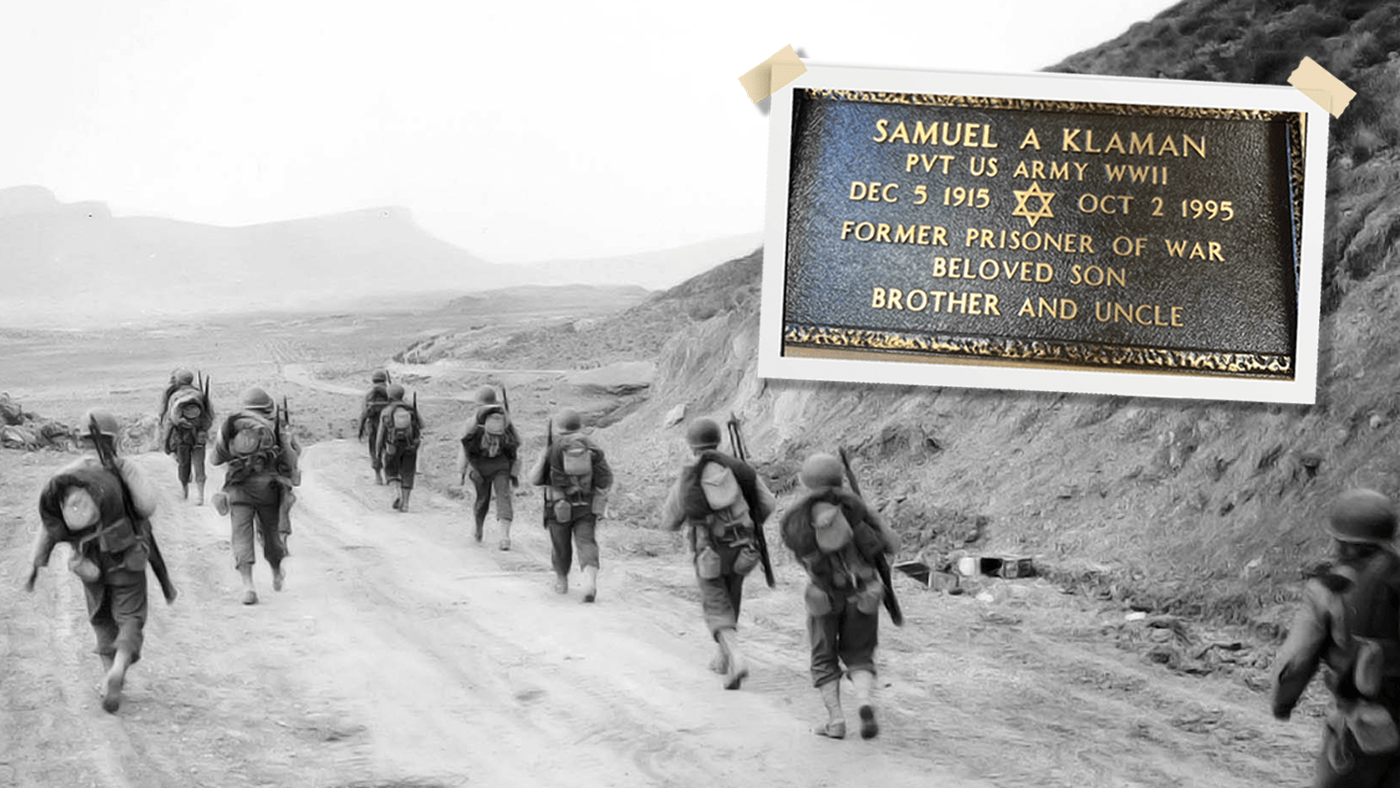

With help from VBA and NCA, an administrative correction honored a WWII soldier's service and Jewish identity.