It was a warm Sunday afternoon on May 20, 1917, as nurses and doctors of Chicago’s Base Hospital Unit No. 12 gathered on deck of the U.S.S. Mongolia to watch Navy gunners conduct target practice.

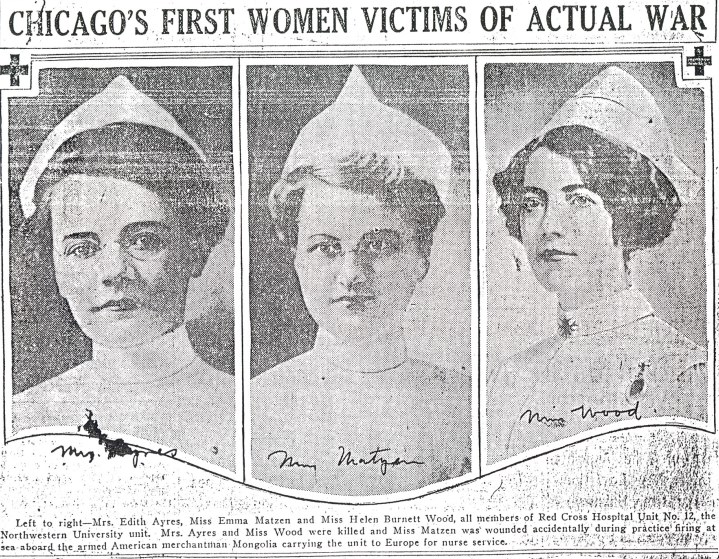

Laura Huckleberry, one of the nurses standing on deck, had grown up on a farm near North Vernon, Indiana, and graduated from the Illinois Training School for Nurses in 1913. With Huckleberry were her roommates, Emma Matzen and Edith Ayres, also graduates of the Illinois Training School Class of 1913 and Red Cross Reserve Nurses selected for coveted spots in the hospital unit.

Also enjoying the Atlantic breezes while lounging in deck chairs or standing at the ship’s railing, the group included Scottish-born Helen Burnett Wood, a nursing supervisor at Evanston Hospital. Wood’s mother had protested her daughter’s decision to join the unit, but the 28-year-old Wood had written just before the ship sailed to tell them not to worry.

But Wood’s mother’s worst fears soon materialized.

“We watched them load and fire and then Emma said, ‘Somebody’s shot,’” Huckleberry later wrote of the event in her diary. “I turned and saw two girls on the deck and blood all around.”

Pieces of flying shrapnel struck Ayres in the left temple and her side, while Wood’s heart was pierced. Both were killed instantly. Matzen suffered shrapnel wounds to her leg and arm. As doctors and nurses attended to their fallen comrades, the ship turned around and returned to New York. The wounded Emma Matzen was taken to the Brooklyn Naval Yard Hospital, then transferred to New York Presbyterian Hospital and later to convalesce at Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, D.C.

These three women became the first American military casualties of World War I. But it was unclear whether they were entitled to military benefits. Before their bodies were shipped home, Ayers and Wood were honored by the American Red Cross in a memorial service at St. Stephen’s Church. Their coffins, placed side by side, were draped with the Allied flags as New Yorkers paid their respects.

Although technically not buried with full military honors, the two nurses were honored in their local communities in elaborate public services described as “similar to those accorded the sons of Uncle Sam who fall on the field of battle.”

In honor of their martyred patriot, 32 autos in a “slow and solemn march” accompanied the hearse carrying Edith Ayers’ casket from the rail junction to Attica, Ohio. Area schools were closed for two days and most of the community paid their respects as her body lay in state in the Methodist Church. The burial concluded with a 21-gun salute from the 8th Ohio National Guard as a delegation of Red Cross nurses and representatives of the governor and the state of Ohio stood in silence.

Wealthy financier and former Evanston mayor James Patten, whose wife was a friend of Helen Wood, telegraphed his New York representative to have the body shipped to Chicago at his cost. Evanston Hospital, Northwestern University and First Presbyterian Church officials took part in planning the memorial services after obtaining the consent of relatives.

More than 5,000 people lined the streets of Evanston to view her funeral escort, which included a marching band, 50 cadets from Great Lakes Naval Station, Red Cross nurses, hospital and university officials and other dignitaries. Following church services, a contingent of Red Cross nurses accompanied grieving family and friends to the gravesite.

Part of the ambiguity about the military status of these nurses came from the fact that they were enrolled by the American Red Cross before being inducted into the U.S. Army. They also served without rank or commission. Although the Army and Navy had formed nursing corps before the war, this was the first time they had inducted women in large numbers.

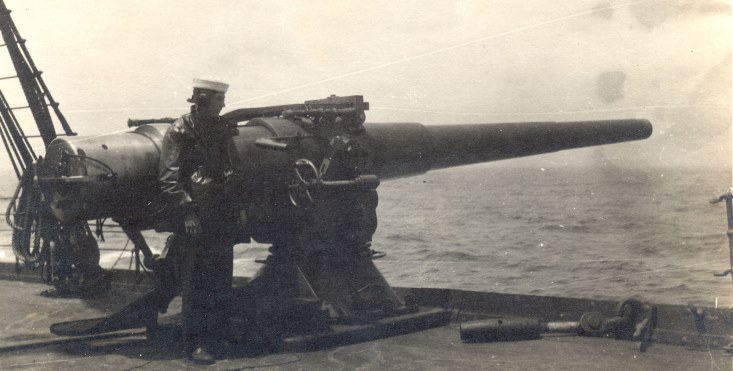

The Senate Naval Affairs Committee investigated the incident, determining that it resulted from the malfunctioning of the brass cap on the powder cartridge case and ordering changes to naval guns to prevent recurrence of such mishaps. But as U.S. war casualties mounted, these women were soon forgotten.

Emma Matzen recovered from her injuries and rejoined her unit in France later that year. In 1919, she returned home to Nebraska, where she and a sister, also a nurse, ran a small hospital. Each adopted infant girls who had been abandoned at the hospital; both girls later became nurses as well. Matzen moved to Ft. Wayne, Indiana, in 1949 where she did private duty nursing until she was 87. She was the only female among the 49 residents in her local VA Hospital; she died in 1979 at the age of 100.

Until the mid-1940s, the Edith Work Ayers American Legion Post in Cleveland was an all-women’s group comprised of former WWI Red Cross nurses and volunteers. The Attica Ohio Historical Society has honored her during annual Memorial Day ceremonies. Ayers’ graveside, although also without mention of any military service, has an American Legion marker. An Attica high school student, with the endorsement of the American Legion, has applied to the Ohio History Commission for a plaque to be placed in Attica in honor of its native daughter.

In Northesk Church near Musselburgh, Scotland, Helen Wood’s name is the first listed on a Roll of Honor of the congregation’s WWI deceased. In 2014, the flag which draped her coffin and her Red Cross pin were displayed in a WWI exhibition at the local museum. But Helen Wood is buried thousands of miles away in Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery. Among the grand tombstones of famous Chicagoans and war veterans, Wood’s simple headstone makes no mention of her military death. Her wartime sacrifice is recognized only by a marker provided long ago by the Gold Star Father’s Association.

On the centennial of the accident aboard the Mongolia, a public wreath laying ceremony will be held at Helen Burnett Wood’s grave site in Rosehill Cemetery May 20. Part of “Northwestern Remembers the First World War”, a series of exhibits, lectures, and commemorations from Northwestern University Libraries will also be part of the remembering of America’s first casualties of WWI. Support of the event is provided by the Pritzker Military Museum & Library.

About the authors: Susan Sacharski is the archivist at the Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, and a subject-matter expert on the nurses of Base Hospital # 12. Marian Moser Jones is a historian and an associate professor in the Department of Family Science at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Topics in this story

More Stories

Summer Sports Clinic is a rehabilitative and educational sporting event for eligible Veterans with a range of disabilities.

Thinking about building a family or exploring fertility treatments? VA can support you with a wide range of services.

Report examines the input of over 7,000 women Veterans: They are happier with VA health care than ever before.

Amazing Story, thanks to the writer for bringing back their memories for all of us.

Thank you very much for writing about these women!

As an historical note the American armed merchant steamer Mongolia of the Atlantic Transport Line is credited with the first shot fired by America in World War I. On April 19th near the end of its voyage to Britain, the Mongolia’s 17 man US Navy gun crew engaged a German U-boat. A single 6″ shell was fired. A hit could not be confirmed but the U-boat was seen to submerge. The Naval inquiry of the May 20, 1917 accident concluded that the brass mouth cup used to seal the propellant charge apparently ricocheted off the water and fragments flew back onto the promenade deck of the Mongolia where the nurses were watching the gunnery drill. None of the gun crew suffered injuries.

Great story. Women have always played an important part of our history.

Very interesting info. I had no idea.