The Warrior’s Ethos is a mindset, a commitment, an oath for warriors of all disciplines. It has existed for many decades. Generically, it’s as follows:

The Warrior’s Ethos

1) I will always put the mission first.

2) I will never accept defeat.

3) I will never quit.

4) I will never leave a fallen comrade.

Over the years, it has been modified to fit each of the branches of the military and accepted by each. The Airman’s Ethos was introduced in 2007 by General T. Michael Mosely, then Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force.

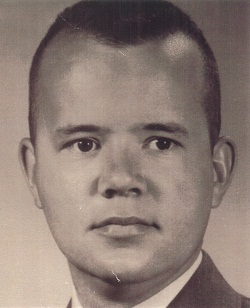

Of particular interest, for this story, is The Fourth Tenet, “I will never leave a fallen comrade behind.” That is a powerful statement! It is a fiduciary statement of allegiance and brotherhood that imbues trust and honor among all warriors. It is intended to apply to all warriors, from the battlefield to the White House. (The president is the Commander in chief of all military forces.) What happens when one party fails or refuses to execute their obligation to bring their comrade home? This is the story of Technical Sergeant Louis J. Clever and his son Paul.

Early morning. The sun was obscured as the first storm front of the season came through the night before making this a cool, blustery day. Lou and his family had already been at Hartsfield International Airport for a couple of hours. The conversation, when there was some, was light.

The days before had been a battle royal in the Clever residence. Deborah, Paul’s mom, was petrified. Lou was heading off to Vietnam. He had volunteered without consulting her. Her fears included Lou not coming back and her having to rear their children alone, a skill she felt totally inept at doing. But now, at the airport, a sense of resolve and acceptance had fallen over them. All that was left were long silent stares. The time finally came for Lou to board the plane. Lou turned to Paul, “You’re the man of the house now, Paul. Take care of your mother and sister.” Paul, confused at the task that his father had just assigned him, replied “Okay dad.” then returned the hug and watched his father head out to the waiting airplane. In three days, Lou would be in Vietnam.

Louis J. Clever had been in the Air Force for over a decade. As a company clerk, he wasn’t destined to gain much more, if any, rank. In an effort to dramatically improve his chances for promotion, he cross-trained as a morse-code radio operator in a newly formed group called, the United States Air Force Security Service (USAFSS). He served one tour in Germany, then cross-trained again to perform Airborne Radio Direction Finding (ARDF), then volunteered for Vietnam. He was assigned to the 6994th Security Squadron, stationed at Pleiku Air Base, South Vietnam. The motto of the 6994th was “Alone, Unarmed, and Unafraid.” Members of the 94th generally flew ARDF missions about every other day.

February 5th, 1969: Lou and the rest of the ten-man crew of CAP 72 took off from Pleiku in their venerable EC-47, tail number 45-1133 at approximately 6 am. At about 8am while over South East Laos, Major Robert “Bob” Olson (Navigator) checked in to confirm positioning just prior to their run near the DMZ. That was the last anybody ever heard from CAP 72.

On Feb 10, a 2nd Lt. and a chaplain knocked on Deborah Clever’s door and asked, “May we come in?” Deborah stood motionless as she considered the scene. Military families always expect the worst news in situations like this. She weakly opened the door. “The Secretary of the Air Force has asked me to express his deep regret…,” the 2nd Lt. began. “Who are these men?” Paul insisted as he and his sister clamored into the room.

“These men are here to tell us that your dad is lost, and they can’t find him,” explained Debra in terms her children could understand. “Lost!? I can find him! I’m good at finding things….,” Paul went on. Fate would have those words ringing in Paul’s ear for the rest of his life.

Over the years since the Vietnam conflict, every President that had something to do with Southeast Asia swore that “The US did not have combat boots on the ground in Laos.” Only clever semantics would allow them to get away with such a lie. They failed to mention that there were combat troops in the air, that there were multiple CIA sites, POW’s and KIA’s in Laos. Of course, the US had plenty of combat assets in the area: CIA trained guerrillas (CAS), CIA listening posts (Lima Sites), along with unacknowledged incursions by combat troops chasing the Viet Cong across the border. It was June of 1969 and once again there was a dark blue sedan in front of the house. This time, it was confirmation that Lou’s airplane had been found. Deborah was told the entire crew had been lost. A CIA trained Thai guerrilla group had received word of a plane crash near one of the web like dirt paths that made up the Ho Chi Minh trail in southern Laos. They found the site and collected remains in a co-mingled sack. They also collected a few identifying artifacts to connect this site with the CAP 72 loss.

The lead forensic specialist at the Army Mortuary Affairs located near Tan Son Nhat Air Base determined only seven of the crew were present in the co-mingled remains and recommended a return to the crash site for a “Maximum Recovery”. The recommendation was denied and in spite of the specialist’s protests, the remains were sent to Dover Air Force Base for final processing and eventual burial in a group grave. Jefferson Barracks Cemetery, in St Louis, seemed central to all ten families involved, therefore it was chosen for the group burial site for the ten-man crew. There were two closed caskets, one for the officers and one for the enlisted: though the remains were still co-mingled. The headstone listed ten names even though there were only seven present and one identified (Sgt. Clarance McNeill). Family members were never told that three of their loved ones’ remains were still unaccounted for and remained in Laos though many suspected the accounting was incomplete.

Young Paul surveyed the scene, “Mom. Why aren’t there ten caskets instead of two?” The answer to the child’s innocent question was too gruesome to put into words. It was all that Deborah could do to contain an uncontrollable grief, so she detailed Paul and his sister’s care to their Grandparents. Time marched on, sometimes excruciatingly slow. Deborah built her life in Hartwell, GA. The kids had as normal of a life as possible. As soon as Paul graduated from high school he left home and the next year he went into the Navy as a Nuclear Propulsion System Operator. A few years after getting out of the Navy, Paul’s marriage of ten-years ended.

In 2000 Paul returned to college to complete his degree. During this time he began researching the Library of Congress database on POWs and MIAs. He asked questions, studied maps, and searched the Internet. Through long and detailed research, details of his father’s mission, death, and most importantly: the general location of the CAP 72 crash site inside the Laotian Jungle became clear. Paul began to think, “I wonder if I could actually find the crash site!” In 2002 some Thai friends of Paul connected him with a young lady in Thailand which they thought he should meet. In May 2003 Paul flew to Thailand and spent a month getting to know her. After a year of separation as immigration requirements were being met Nita became his new wife. In 2009 Paul moved to Bangkok, Thailand and took a position as a Southeast Asia Service Manager for his employer. It was here that Paul began putting together a plan to resolve the whereabouts of his father and the uncertainty of his father’s accounting.

As part of the ongoing research, it was learned in 1995, while searching for a different American crash site in Laos Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) team members came across the crash site of CAP 72. Not knowing what had been found, the team made a brief search of the site and found an identification tag for Captain Walter Burke: the co-pilot of CAP 72.

The discovery of the crash site was very fortuitous. It seems the guerrilla group that first found the crash site originally had miss-calculated the coordinates. The team that had found the dog tag recalculated the coordinates using longitude and latitude. They were five miles away from original coordinates given by the guerrillas in 1969. This was the key information needed to take the search from ideas and transform them into action.

It would be 2011 before Paul felt confident enough to attempt an expedition. In hindsight, the first trip into Laos was an abject failure. But in a holistic sense, it was a complete success. The trip helped Paul identify the correct questions which needed to be asked if a determined effort was to be undertaken. Paul resigned his position in Bangkok, returned to the United States, and began to build his determined effort. Much to his surprise, there was only one person willing to travel with Paul to the Laotian jungle in search of the crash site. It was Nita: his Thai-born wife. The trip began in December 2012 in the city of Xekong, Laos. Paul had rented a motorcycle and the two started north up the Ho Chi Minh Trail. What was thought to be a one hour trip turned into almost five hours as the rough road took its toll.

After arriving at the general area of the crash site they stowed their motorcycle in an area out of sight from the road and began the arduous trip into the jungle. It would take two and a half day of searching the jungle before a glimmer of light from the jungle floor caught Paul’s attention. It was a shard of glass. After so much time looking at the jungle floor and seeing nothing this was instantly known to be a significant find. Closer inspection revealed small pieces of metal, electronic components, and debris. They had found the crash site.

It was not until the third day at the crash site did the couple finally find the first human remains. Nita was on her hands and knees, her face just inches from the ground, surveying every twig and stone, when finally, she yelled out, “Paul! Come look at this!” It was the matrix created by the bone marrow which identified Nita’s find as human remains. After learning what to look for it was only a short time before Nita found another and then another. When they left the crash site there were nearly forty of human remain fragments recovered: along with one rock. This was later acknowledged by a JPAC Staff Member as quite exceptional for remains visual identification in the field.

After returning to the United States Paul contacted officials at the Air Force Mortuary Affairs located at Dover Air Force Base. After repatriation, the remains were handed over for analysis. Modern DNA analysis proved that these were the remains of the three of the CAP 72 crew, and yes, one of the bones was that of Technical Sergeant Louis J. Clever, father of Paul Clever. JPAC knows, within inches, where the crash site is located, but to this day have not returned to bring the other men of CAP 72 home. Paul continues to search for MIA’s in Laos. When asked how it made him feel to find his father he replies, “I found the cure for insanity!”

The Crew of CAP 72

• Lt. Col Harry T. Niggle – Pilot NAVIGATOR – Identified

• Major Homer M. Lynn – Pilot – Missing in Action

• Major Robert E. Olson – Navigator – Identified

• Capt Walter F. Burke – Co-pilot – Presumptive finding of death – recovered identification tag.

• MSgt Wilton N. Hatton – Aircraft engineer- Missing in Action

• TSgt Lou J. Clever – Radio Operator Morse intercept SUPERVISOR X ARDF AMS Airborne Mission supervisor – Identified

• SSgt James V. Dorsey – Radio Operator – Identified

• TSgt Hugh L. Sherburn, – Radio Operator ANALYST – Identified

• SSgt Jimmy H. Gott – Radio Operator MORSE Z2 – Identified

• Sgt Clarence L. McNeill – Radio Operator linguist Z1- Identified

O R Graves and Paul D Clever

Topics in this story

More Stories

Soldiers' Angels volunteers provide compassion and dedication to service members, Veterans, caregivers and survivors.

Veterans are nearly three times more likely to own a franchise compared to non-Veterans.

The Social Security Administration is hoping to make applying for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) a whole lot easier, announcing it will start offering online, streamlined applications for some applicants.

It was very interesting

Truly enjoyed the written journey of Paul’s adventure to find his father’s remains! Two up, great read.

An incredible story of perseverance. Engaging as well as entertaining. A captivating page turner I thoroughly enjoyed.