Norman R. Smith grew up in the famous Tremé neighborhood in New Orleans. He was one of those children who knew what he wanted to do at a young age. Smith didn’t want to be a pilot or a police officer, or even a soldier. He wanted to be a historian. Specifically, he wanted to record and preserve black history.

As a boy, some of the first stories Smith heard were of family members from generations past. He knew that his father had been in the military, along with his grandfather and great grandfather. In fact, his mother’s great grandfather had served in the war of 1812, and her great uncle had fought in the 9th Cavalry Heavy Artillery in the Civil War. Their stories fascinated Norman.

As early as the fifth grade, Smith had the idea to make calendars that would bring to life the stories of black historical figures. His goal was to share the many contributions black people had made to American society, especially some who might be lesser known.

“The point was to do something positive,” he explained. “So little black kids like me could have something to look forward to. To look up to.” For a time, it remained just an idea.

Smith finished school and trained as a mortician, perhaps because it was a career that would allow him to honor those who had passed on. Soon after finishing his training, he was drafted into the Army where he was to serve as a telephone technician. But after arriving in Vietnam, he was transferred to work as an identification specialist and later he was tasked with preparing fallen heroes for return home to their families. After Smith returned from Vietnam, he worked as a funeral escort stationed at Oakland Army Base.

Upon discharge from active duty, Smith resumed his career as a mortician. He worked in other fields over the next few years, including for the Louisiana Department of Veterans Affairs. After leaving that position, he decided to take the opportunity to achieve the goal he had set for himself many years before. He began what would eventually add up to nine years of research on historical black figures from Louisiana. In 1983 he published his first calendar under the title Etches of Ebony Louisiana.

“I called them Etches of Ebony Louisiana because I was documenting the history of our people,” said Smith. “I was etching their names into the history books.”

Smith continued to produce the calendars until 2004. During that time, he told the stories of thousands of people, one for each day on the calendar. He also created special calendars that featured the African American churches and historically black colleges of Louisiana.

When Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans in 2005, it destroyed much of Smith’s research, and nearly all the work he had produced.

“There were seven feet of water in my house,” he recalls. “My file cabinets were floating.”

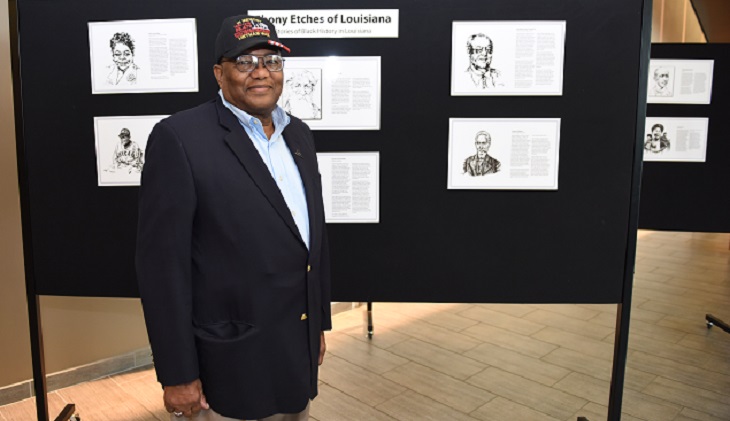

In 2018, Smith met the director of the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System, Fernando Rivera. Smith shared his story with Rivera, and Rivera had an idea. Over the next few months, Smith worked with the Rivera’s team at the Veterans medical center in New Orleans to create a display that would tell some of the stories Smith had hoped to preserve. Many of those featured in the exhibit were Veterans. They all had a connection to the local area and made an impact on the region’s history. The installation featuring Smith’s work is currently on display at the New Orleans Veterans medical center in honor of Black History Month 2019.

Were it not for the dreams of a young Norman Smith, some of the people he later worked so hard to research might be that much closer to being forgotten. We thank him for his contributions and proudly share his work with the community so that the stories he shared, and his own story, might live on to inspire someone else.

Topics in this story

More Stories

VA recently developed a pilot program providing direct and specialized assistance for the 65 living Medal of Honor recipients nationwide.

This year, Veterans Day ceremonies recognized by VA will be held in 66 communities throughout 34 states and the District of Columbia to honor the nation's veterans.

A personal reflection on generational service from VA Deputy Assistant Secretary Aaron Scheinberg.