September is known as Suicide Prevention Month, but South Texas VA employees and community partners have been collaboratively looking for solutions to this problem all summer.

Erik Zielinski, the South Texas VA Fisher House program manager and Marine Corps Veteran, saw a need after he experienced members of his unit committing suicide. He started the Suicide Prevention Resources meeting to combat the insidious public health crisis that takes the lives of 20 Veterans a day.

The Suicide Prevention Resource Meeting was gaining steam off another successful Mental health Summit in August, organized by Dr. Betsy Davis, South Texas VA Local Recovery Coordinator.

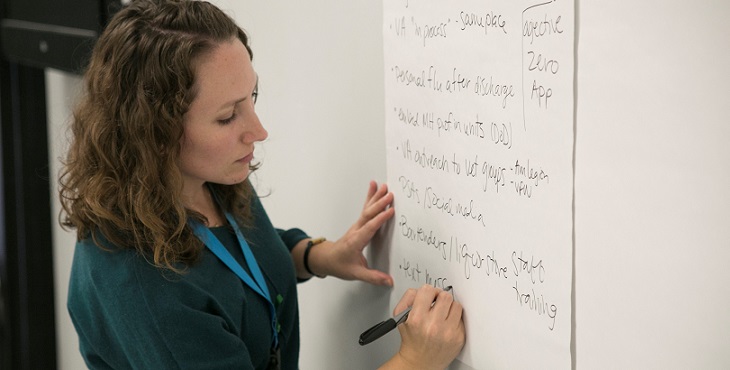

The South Texas VA Recreation Center was transformed into an idea factory for the monthly Suicide Prevention Resources Meeting. Attendees took part in an interactive exercise. The participants come from all types of backgrounds and experience levels, but with the common thread of preventing suicide.

She opened the August meeting with a recap of the summit:

“One of the biggest takeaways we heard was more proactive information sharing,” she said.

Davis and her team of volunteers got that feedback through a series of breakout sessions designed to stimulate interaction and collaboration between the VA and its community partners. Davis also highlighted that the attendees thought some of the suicide prevention challenges were to decrease stigma of mental health and clear up misinformation about the VA.

The keynote speaker for the event, retired Army Veteran and Wounded Warrior Wellness Team Lead Armando Franco, experienced some of that stigma and misinformation first-hand.

After finishing his career, he wanted to still be “around” the military, so he took a gig in military contracting. He was gone for two years overseas. When he came back, he sifted through two years of mail, literally catching up with his life. Later, his boss pointed out to him that he had changed. Franco fell into a dark place filled with destructive behaviors. “All I could hear was all the noise and the pain and suffering. I sat there with a loaded .45 ACP. I began drinking heavily and began doing my medication.”

He thought between the gun and the pills, he would get the job done.

“I woke up the next morning with a round chambered with a magazine in my lap,” Franco said. “It didn’t happen, and to this day, I have no idea what happened.”

After that experience, he sought help.

Thinking creatively, critically

Franco’s example fed into Dr. Davis’ theme for the meeting. She used an analogy of swimming upstream and suicide. “The VA Whole Health program is a fantastic example of a service the VA is providing,” Davis explained. “It’s not necessarily for when you have a problem, but what is important to you, what your goals are, and what we can do to help you get there.”

Davis went on to explain suicide prevention is a crisis, and that it is located downstream. VA has services in place for crises: suicide prevention coordinators, mental health staffing emergency rooms across the country and the Veterans Crisis Line.

With a room full of providers, she implored them to think more about the journey toward that end point. “So, the big picture point is what ever promotes mental health recovery and quality of life for Veterans and their families is suicide prevention,” Davis said.

“Finding a job is suicide prevention, connecting with social support is suicide prevention, restarting a hobby is suicide prevention,” Davis said, pointing out to those program managers in the room.

That led Davis to begin a collaboration exercise with the group, breaking them up by tables and challenging them to brainstorm how the services they represent and their personal experiences they’ve had could be parlayed into mental health recovery tactics.

The responses were diverse like the audience. Some of the senior Veteran Service Organization representatives suggested an old school approach with more boots on the ground and mentoring those transitioning service members that Davis said are most vulnerable. “Sometimes the Veteran is a year, or even two into their transition before they have lost a couple of jobs, or they are having problems in their relationship to figure out, hey, something is really going on here,” Davis said.

Prevention and cure

The antithesis of those “old hat” suggestions was a young Marine Veteran, Ralph Hernandez, who very directly stood up in front of the crowd, introduced himself, then raising his phone, began live streaming. “Hello everyone, my name is Ralph Hernandez, I am a Marine Veteran and I am here at the suicide prevention meeting,” he said while looking at himself in his screen. “If you are having any thoughts about harming yourself, you can reach out to me at any time.”

The room buzzed. His demonstration echoed back to what Franco described in his first mental health encounters at the VA. “My doctor said there were three factors that lead a Veteran to suicide: the lost sense of belonging and being a perceived burden,” he said, mentioning the first two. By reaching out, Hernandez might have eclipsed two of those reasons for a Veteran who was watching.

Davis collected the responses, then will use the feedback to develop the modes and methods of collaboration in the future.

“How do we do something differently and as a community, not focus all of our efforts at the end of the line,” Davis said.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Steven Goetsch is a public affairs specialist at the South Texas Veterans Health Care System

Topics in this story

More Stories

The Medical Foster Home program offers Veterans an alternative to nursing homes.

Watch the Under Secretary for Health and a panel of experts discuss VA Health Connect tele-emergency care.

The 2024 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report provides the foundation for VA’s suicide prevention programs and initiatives.

most of those that commit suicide are always felled with depression, we should also focus on what causes such depression

been able to prevent suicide is part of the government responsibilities, so the government should take responsibilities on citizens