This is the second installment in a three-part series on the officers and men of the 349th Field Artillery Regiment in World War I. This series of blog posts profile the World War I service and post-war experiences of three Veterans of the 92nd Division’s 349th Field Artillery Regiment, one of the Army’s first predominately African-American artillery units. Alabaman and Colonel Dan T. Moore was its reluctant white commander. First Lieutenant Everett Johnson, a black officer, commanded Battery E, and Sergeant Robert Samuel Chase was one of Johnson’s non-commissioned officers. All three survived the war and are interred in national cemeteries maintained by VA’s National Cemetery Administration. Both Johnson and Chase, highly skilled and educated, faced their own challenges after the war.

Colonel Dan T. Moore (1877-1941) commanded the 349th Field Artillery Regiment in France during World War I. As founder and first commandant of the Army School of Fire and Field Artillery at Fort Sill, OK, he was one of the Army’s most respected artillery officers. He served in the Spanish-American War, then as military aide to President Theodore Roosevelt during his first term. Moore garnered national attention in 1917 when Roosevelt revealed publicly that a young artillery captain that he sparred with often between 1904 and 1906 blinded his left eye in the boxing ring. Moore did not know he had injured the president until he read it in the news.

As Americans learned about Moore in late 1917, he was transferred from Fort Meade, MD, to Camp Dix, NJ, to take command of an all-Black artillery regiment. This assignment was a disappointment. One contemporary remarked that that assignment – to a “negro regiment” – would certainly “be hard on Dan” and was “mighty ungrateful of the [Wilson] Administration.” Much later, his son-in-law affirmed that Moore felt the same: [H]e “was born in Montgomery, AL. He appreciated the active duty. He did not appreciate serving with a Negro outfit.” Moore felt he was expected to fail because the General Staff did not want the all-Black brigade to succeed and that it assigned its best artillery officers to the unit just so they could say “this new venture in colored artillery had a fair show.”

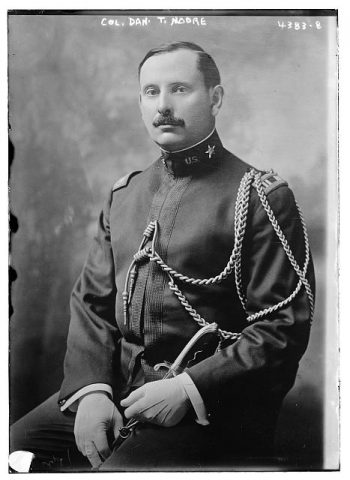

Colonel Dan Tyler Moore who was a military aide to President Theodore Roosevelt, ca. 1917. (Library of Congress)

Moore did not resign himself to failure, however. He anticipated that his men would likely never get to the Western Front but resolved to create a capable unit to force Army leadership to justify combat exclusion.

The biggest obstacle was the quality of draftees. Artillery was a technical field that required a general understanding of science and math, and he was predominately receiving Southern farmers. He and other white officers aimed to train proficient Black artillery officers and to get better-prepared draftees and volunteers. One white captain with the unit, Royal F. Nash, had worked as secretary of the NAACP and spearheaded a recruiting drive in black communities for the 349th. As Black officers completed training, Moore sent them home to find new recruits with high school education, at a minimum. Moore’s work helped form one of the most educated African-American units in the U.S. Armed Forces.

When Moore led white units, his counterparts described his relationship with officers and subordinates glowingly. It is not known if Moore’s Black soldiers felt the same. Regardless, he created a high-performing unit that defied expectations and was given the chance to prove themselves on the battlefield. Moore’s Black artillerymen helped push the Germans toward defeat in the final weeks of the war. But the men Moore led in France were among the last he would command. He resigned from the active Army after returning home from the war, accepted a permanent commission in the Officer’s Reserve Corps with the rank of colonel, and was an active reservist through 1935.

Moore’s family described him as a somewhat lonesome man in retirement, someone without purpose outside of the Army. He died of an apparent heart attack on April 15, 1941, and is buried in Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery (Section E, Site 44). In December 1958, the officers of the artillery school he created installed a bronze plaque at his gravesite, which was eventually attached to the back of his headstone.

Richard Hulver is a historian at VA’s National Cemetery Administration.

Topics in this story

More Stories

This year marked the 75th year of the 2024 Gravois Trail Memorial Day Good Turn Boy Scout flag placing at every gravesite at Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery.

NCA's Cemetery Restoration Project educates communities about private cemetery owners and the caretakers who honor and memorialize Veterans buried without headstones. The restoration project also restores these private resting places to reflect the dignity and honor these Veterans deserve for their service and sacrifice to our nation.

Rubber Tramp Rendezvous is held annually in January, and it provides an opportunity for those who live a mobile lifestyle—in vehicles such as vans, RVs, and buses—to learn more about the benefits and support available to them.