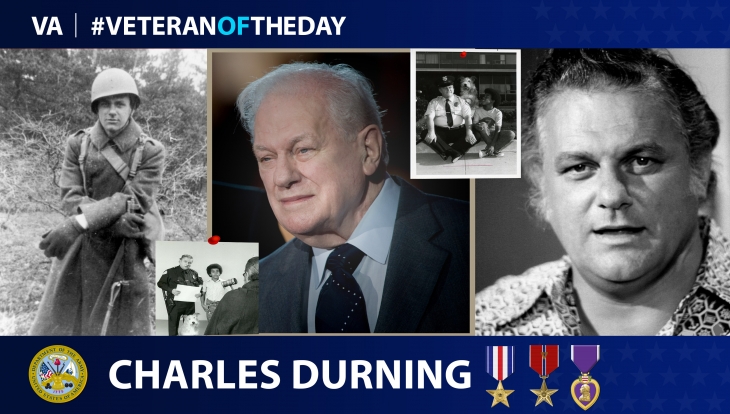

Today’s #VeteranOfTheDay is Army Veteran Charles Durning, who served as an infantryman during World War II and later became a prolific actor.

Charles Edward Durning was born in Highland Falls, New York, in February 1923. He had nine siblings, five of whom died during childhood of either smallpox or scarlet fever. Durning came from a poor family. His mother was a laundress at West Point, washing the uniforms of cadets at the U.S. Military Academy. His father, a World War I Veteran who had lost a leg and was exposed to mustard gas, could not work and died when Durning was 12.

After a high school counselor told him that he had no artistic talent and should train to become an office worker, Durning dropped out and began working as an usher at a burlesque theater at age 16. One night, a stand-up comic was too drunk to perform. Durning, who had been studying the routines of comedians he saw on stage, took his place. From the moment he heard the audience laugh, Durning knew he wanted to become an actor.

However, World War II interrupted Durning’s aspirations. The Army drafted him at age 21. He was part of the first wave of soldiers to land on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. Durning was the only member of his unit to survive the assault.

“I was the second man off my barge,” Durning said, “and the first and third man got killed.”

Days after arriving in France, a German land mine injured Durning. He spent the next six months recovering from shrapnel wounds in England, received his first Purple Heart, and returned to the front lines.

While fighting in Belgium, Durning came face-to-face with a teenage German soldier. He couldn’t bring himself to shoot the young man, but when the soldier stabbed him with a bayonet, Durning defended himself and killed his attacker with a rock. During the Battle of the Bulge, Germans captured Durning. He was one of only a few soldiers to survive the Malmedy massacre when German soldiers opened fire on nearly 90 prisoners of war. For his injuries, Durning received his second Purple Heart.

In March 1945, Durning was moving into Germany with the 398th Infantry Regiment when he took a bullet to the chest. That bullet effectively ended Durning’s service; he spent the rest of the war in the hospital recovering from his wounds. He received his third Purple Heart and discharged in 1946 with the rank of private first class.

After the war, Durning returned to acting. Throughout a career that spanned more than half a century, Durning appeared in over 200 films, television shows and plays—he reportedly never turned down a role—and was nominated for multiple Emmy and Academy Awards.

Despite his professional success, Durning remained haunted by his wartime experiences. In addition to his Purple Hearts, he received a Silver Star for his actions during the war, but later in life, he refused to talk about the details of his service, describing the memories as too painful.

“You know, everybody who was there [at Normandy] is in some state of denial,” Durning said in 1994. “There are things I’ll take to my grave.”

Durning passed away on Dec. 24, 2012, at the age of 89.

We honor his service.

Nominate a Veteran for #VeteranOfTheDay

Do you want to light up the face of a special Veteran? Have you been wondering how to tell your Veteran they are special to you? VA’s #VeteranOfTheDay social media feature is an opportunity to highlight your Veteran and his/her service.

It’s easy to nominate a Veteran. Visit our blog post about nominating to learn how to create the best submission.

Contributors

Writer: Stephen Hill

Editors: Alexander Reza and Merrit Pope

Fact checker: Anthony Mendez

Graphic artist: Philip Levine

Topics in this story

More Stories

This week’s Honoring Veterans Spotlight honors the service of Army Veteran David Bellavia, who received a Medal of Honor from the Iraq War’s deadliest operation, the Second Battle of Fallujah.

This week’s Honoring Veterans Spotlight honors the service of Army Veteran Scotty Hasting, who served in Afghanistan.

This week’s Honoring Veterans Spotlight honors the service of Army Veteran Roy Sheldon, who served in 97th General Hospital in Frankfurt, Germany.

Are the medals portrayed beneath his photo his? If not 100% accurate, FIRE the moron that put them there.

Thank you for writing Mr. Durning’s story..It is good to know that we remember his service long after his passing..this is not a sad story but one that leaves us with a sense that America still produces brave and selfless individuals.

,