When Caleb Clark returned from Iraq, he couldn’t quite figure out what was going on.

“There were a lot of instances where I was wondering why my heart was racing, why my blood pressure was going up, why I was blacking out,” said the 24-year-old Army Veteran. “I thought I’d get over it eventually. But it just kept getting worse. There was more going on than I realized. Something was wrong —really wrong.”

Ninja

Because of his inability to control his anxiety, Clark had difficulty finding and keeping a job, and paying bills. Eventually he and his girlfriend Alysse were evicted from their apartment.

“I would just walk off jobs if something happened that triggered me,” Clark explained. “I’d get overwhelmed and just leave. No notice, no nothing. I was like a Ninja. I was just gone. And then when they’d call to see where I was at, I wouldn’t answer the call. I felt like I was a target and they were hunting me down.”

Clark and Alysse had no place to live but his pick-up truck. Life was getting bleak in a hurry.

“Even the truck was breaking down,” said Alysse, 24. “Everything bad that could possibly happen to us was

happening all at once.”

And Baby Makes Three

“We were living in my truck and I was working three jobs,” Clark said. “I was detailing cars, doing stucco work, cooking in a general store. Anything I could do, I was doing. Two days after we became homeless we found out Alysse was pregnant. I told her, ‘You can’t be pregnant and be homeless with me.’ So we found her a shelter to stay at.”

Alone in his truck without Alysse, Clark began slipping into a dark place.

“I just started having some real depression,” he said. “The anxiety had been there for a while, but now it got to a point where I became suicidal.”

A Final Goodbye

It didn’t take long for Clark’s suicidal thoughts to transform into a concrete decision to end his own life. Before doing so, however, there was someone he needed to see.

“I went to the shelter to see my girlfriend one last time,” he said.

“I had no idea he was coming to say goodbye,” Alysse recalled. “That was the day of my ultrasound, so I thought he just wanted to come with me to my ultrasound.”

But apparently fate had its own reasons for guiding Caleb Clark to this particular place, at this particular moment.

“The lady who runs the shelter figured out that something must be wrong, because she got me on the VA crisis line,” he explained.

It was the phone call that would change Clark’s life. Following his conversation with a crisis line counselor, he enrolled in an eight-week residential PTSD program at the Waco VA.

“That was the best program for me,” said the former Army specialist. “There’s eight of you that go through the program at the same time. We all went through it together. You have to open up to each other about your experiences.

“There’s a social worker and a psychiatrist who run the discussion groups,” he continued. “And even when they’re not leading a group, you can talk to them whenever you want, which really helps. They want you to think about your experiences, talk about them, and write about them.”

The Buddy System

Clark said the key to the whole program is the friendships that are formed during those critical eight weeks.

“It’s life-changing,” he said. “You don’t feel alone anymore, because there’s other Veterans to talk to, and relate to. All the guys who were in that group with me, I’ve got their phone numbers and I talk to them every week. You show up there with no friends, and you leave with the best friends you ever had in your life. Veterans need other Veterans they can talk to. You need your buddies.”

Alysse said she now sees a noticeable difference in Clark’s demeanor.

“The support system after the program ends is absolutely crucial.”

“I can tell there’s been a huge change in the way he thinks and acts,” she said. “He’s more relaxed; he seems to know how to handle situations now. Whenever he feels weird, he seems to know how to handle it. I can tell.”

Clark emphasized, however, that it’s what happens following the eight-week program that really matters.

“In the program is where you face your demons,” he said. “They teach you how to face your demons. But after the program ends, the main thing is having support, having people you can talk to. I’ve got a great support system now. So whenever I feel like leaving a job, I have people I can call. They can talk me down, get me back to normal. They can help with the anxiety and the fear.”

A Dangerous Thing

Clark, who joined the Army at 17, said he understands why so many Veterans are reluctant to ask for the help they desperately need.

“In the military they train you to handle things on your own,” he said. “So a lot of Veterans don’t ask for help because it’s ingrained in them to go it alone. So they isolate. And isolating yourself is the most dangerous thing you can do.

“I was almost a statistic,” he added. “But I want the Veterans out there to know it doesn’t have to be like that. I was as low as possible, and now I’m doing fine. When I finally asked for help, all these people were there for me. They showed me that they cared about me.”

To learn more about how VA is helping Veterans with PTSD, visit www.ptsd.va.gov

Need immediate help? Call the Veterans Crisis Line at 1-800-273-8255 (Press 1) or visit www.veteranscrisisline.net

Topics in this story

More Stories

One strategy credited for the improvement is a focus on building trust and stronger patient-provider relationships.

Army and Marine Corps Veteran started making models after being hospitalized at Connecticut VA.

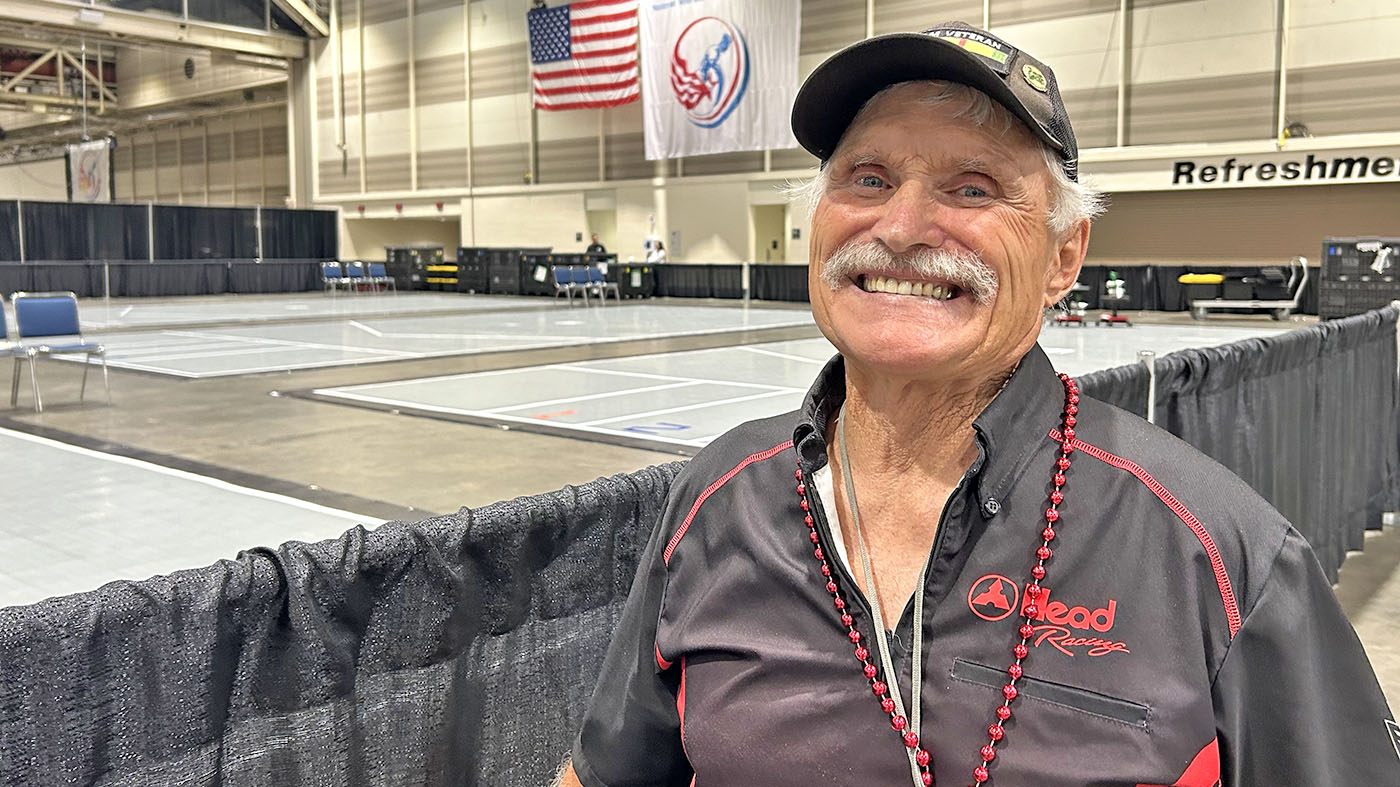

Veteran Hank Ebert is a bit of a superstar in the National Veterans Wheelchair Games. He has been attending since 1993.

Stumbled upon this while researching musicians who committed suicide. And I’m glad I took the time to read, even though this isn’t exactly what I’m looking for. Caleb’s photo with Alysse and Taylor is just so heartwarming. We wouldn’t have seen this family if it weren’t for the shelter lady and VA. Kudos for helping Caleb!

Congrats to VA and congrats to Clark. Really wish you the best and so glad you finally got a hold of things.

It is imperative that my brothers-in-arms who have been diagnosed with PTSD and/or MST to get to the VA as soon as possible. Doing nothing will not end well. For a longtime, I managed to do this on my own in a time when PTSD/MST was not widly acknowledged. I am very happy to see that alot of vets from Iraq and Afghanistan getting the help they need…

Amen Clark

I appreciated the article regarding Clark, the veteran with PTSD. I can relate to not knowing what to do, anxiety over it, fear and finally, withdrawal giving way to depressing preparation for the inevitable end. The hopelessness of homelessness exacerbating negative emotion. Ya get swallowed up in it and realize your alone in a new jungle. Good for Clark and his family’s second chance.