On Jan. 27, the nation and the VA family lost Corporal Alyce Dixon, a courageous Veteran, member of the Greatest Generation, and — I can tell you from having met her at the Fisher House here in Washington, D.C. — a remarkable, generous and good-humored lady. Cpl. Dixon was 108 years old when she passed away at our D.C. VA Community Living Center — deeply respected and much loved by those privileged to know her.

Sec. Bob McDonald talks with former Army Cpl. Alyce Dixon, who recently passed away at the age of 108-years-old.

It is fitting to remember Alyce’s life of service as we observe Black History Month. She was one of the first African American women to join the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) and, later, the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). She served in World War II as a member of the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion — the “Six Triple Eight” — from 1942 to 1946, and she deployed with the 6888th to Europe in 1945. The innovative women of the 6888th were famous for their extraordinary diligence in getting service members the mountains of backlogged mail from home that was often misdirected or cryptically addressed. They persevered, and they succeeded against tremendous odds.

Thanks to visionary leaders like First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and civil rights activist Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, African American women first won the right to defend the nation in the WAAC and, then, the right to join their white WAC counterparts overseas. Under the command of Major Charity Edna Adams, Corporal Dixon’s “Six Triple Eight” Battalion was the only all black WAC unit deployed to Europe in WWII, though other African American women served as nurses in Africa, in Australia, and in England.

Three of Corporal Dixon’s fellow WACs — Sgt. Dolores M. Browne, Pfc. Mary J. Barlow, and Pfc. Mary H. Bankston — died while serving in France. They rest today with other heroes at the Normandy American Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer.

While Alyce and the WACs of the 6888th helped save the world from fascism, they faced discrimination and segregation in Europe, and here at home. Returning to the United States after the war, there were no parades to greet them and no recognition of their service for many decades. But because of their examples of duty and courage, President Harry S. Truman ordered, on July 26, 1948, that “there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” Still, the fight for equality would continue.

After the war, Alyce continued to serving her country at the Pentagon, her fellow Veterans by volunteering at the VA Washington Hospital Center and her community by volunteering at the Howard University Hospital — a wonderful example of selfless service.

African Americans of every generation have given their lives in defense of freedom, even when they did not enjoy the full measure of liberty themselves. They fought during the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Insurrection, the Mexican Expedition, and World War I, to name a few. They are members of the legendary Buffalo Soldiers, the Tuskegee Airmen, the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the Marines of Montford Point, and the “Red Ball Express.” And they are Medal of Honor recipients like Sgt. Cornelius H. Charlton in Korea and Marine Corps Sgt. Rodney M. Davis in Vietnam.

During this year’s Black History Month, let us honor and celebrate all African American Veterans who have risked, and often sacrificed, their lives in service to this great Nation and follow Cpl. Alyce Dixon’s wise advice to live by caring, sharing, and giving.

Topics in this story

More Stories

VA recently developed a pilot program providing direct and specialized assistance for the 65 living Medal of Honor recipients nationwide.

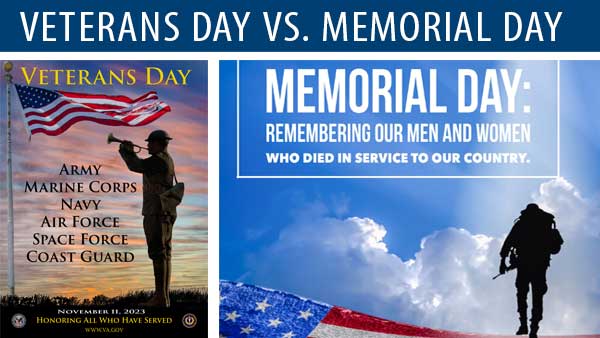

Memorial Day, which is observed on the last Monday in May, was originally set aside as a day for remembering and honoring military personnel who died in the service of their country, particularly those who died in battle or as a result of wounds sustained in battle.

This year, Veterans Day ceremonies recognized by VA will be held in 66 communities throughout 34 states and the District of Columbia to honor the nation's veterans.

How many people know where the term “The Real McCoy”, came from? Back in the 1800s, the railroads used to have a man go around and oil the connections between the rail cars. But then a guy by the name of McCoy came up with a way for them to be self oiling, so things would be safer, and save money. Others tried to duplicate his idea, but people kept saying, “No, no. Get me the Real McCoy.” And yes, he was a black man.

I would hope there could be some remembrance of Ens. Jesse Brown, the first African American navy pilot. Ens. Brown entered.the service in 1948 for training as a navy pilot. He was shot down in his Corsair in December 1950, while supporting 20, 000 or more trapped Marines at Chosin Reservoir.

His Corsair crash landed after an oil line was pierced by enemy fire, causing his engine to fsil.

His friend and wingman, Lt. Tom Hudner, intentionally crash landed his corsair in an effort to extricate his friend from the wrecked plane.

Using axes from a rescue helicopter they were unable to save Ens. Brown from his downed attack aircraft. Hudner was ultimately awarded the MEDAL OF HONOR, by President Truman.

The lives of all concerned with extensive battle narratives was captured in a recent book, Devotion , by Adam Makos.

I hope these brave men can be honored, sometime during Black History month.