Across the U.S., Black men are disproportionally diagnosed with prostate cancer and are more likely to die from the disease than their white counterparts. According to the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), poor outcomes for Black men have been linked in part with reduced access to healthcare and insurance, screening and appropriate treatments.

Studies have shown, however, that Black men who turn to VA for prostate cancer screening and care have significantly better outcomes than those using private healthcare services. This is because VA reduces barriers to access traditionally seen in non-VA settings, which minimize racial disparities.

“VA works hard to ensure every Veteran has access to preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services for prostate cancer,” writes Isla P. Garraway, MD, Ph.D., an attending urologist and translational researcher at the Greater Los Angeles VA Healthcare System. “Ready availability of best-in-class treatments and care is especially important for those Veterans belonging to racial, ethnic, and/or socioeconomic groups who have historically faced disproportionate challenges to accessing quality healthcare.

“In addition, VA has launched several efforts to level the playing field for Veterans to access clinical trials for innovative prostate cancer therapies,” Dr. Garraway adds. “This is a win-win for Veterans and for research, allowing the diverse Veteran population to participate in these trials and researchers to confirm that the findings from these studies are relevant across racial/ethnic groups.”

What is it, and why is it important to VA?

It’s a cancer of the prostate gland – part of the male reproductive system – caused by changes in the DNA of normal prostate cells. Research has shown that each person has different risk factors for prostate cancer based on their individual DNA. This is why VA uses genetic testing, called precision screening, to improve rates of detection, diagnosis, and treatment outcomes for Veterans.

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer at VA with 15,000 new cases every year. The National Oncology Program at VA stands shoulder-to-shoulder with at risk Veterans by expanding access to precision screening and best-in-class treatments for each and every Veteran.

What you can do today

Generally, men should begin talking to their doctor about prostate cancer screening in their mid-40s. However, because Black men are at higher risk, eligibility for screening could begin at 40 years old.

Having a family history of cancer – particularly prostate, ovarian, breast, colon, or pancreatic cancers – also increases risk for prostate cancer.

Precision screening is the best defense for men against prostate cancer. Talk to your doctor to see if precision screening for prostate cancer is right for you.

In addition to its resources for Veterans, PCF also has a guide for African American men looking for further information: Prostate Cancer: Additional Facts for African American Men and Their Families.

Michael Rubin, LCSW-C is a program specialist with VHA’s Office of Healthcare Transformation (OHT) 10T. He is currently supporting the National Oncology Program with Program and Strategic Communications efforts.

Topics in this story

More Stories

One strategy credited for the improvement is a focus on building trust and stronger patient-provider relationships.

Army and Marine Corps Veteran started making models after being hospitalized at Connecticut VA.

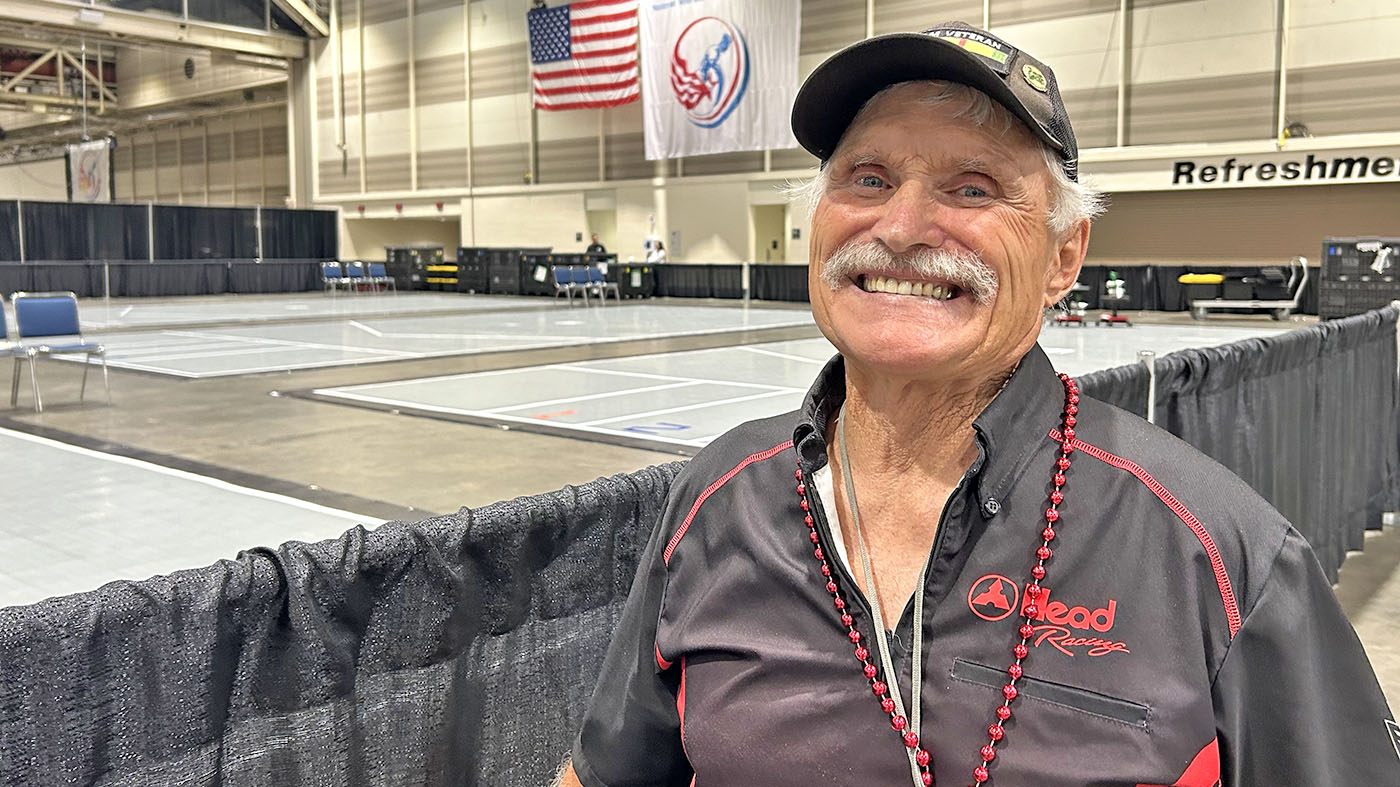

Veteran Hank Ebert is a bit of a superstar in the National Veterans Wheelchair Games. He has been attending since 1993.

VA Urology Clinics determined prostate biopsies “routine” procedures and ceased performing them due to Covid risks. That was my experience in July 2020, despite a PSA increase from 7 to 9 in one month! The clnic staff were very apologetic but could not even guess about a time frame for resuming biopsies. I was fortunate to find a private urology practice that performed the procedure which diagnosed a Gleason Score 7 as well as well as abnormal “ductile” cells known to be aggresive type. With those results submitted to VA, they were most efficient in scheduling surgery which, so far, has a favorable prognosis. Had I delayed the biopsy until VA resumed business as usual biopsies, the outcome may have been very different. Life lesson is: if your PSA doubles in a year and your primary doctor suggests that you meet the criteria for a prostate biopsy, get it done whichever way you can.