1:23 a.m. It’s pitch black in Ramadi, Iraq, except for the cold moon above.

Staff Sgt. Ryan Major and his squad creep silently closer.

The enemy has already killed and maimed American troops with roadside bombs. Intel says the largest cache of explosives is right here. Major is part of the late-night raid to bring them down. This is where he wants to be.

“I was a junior in high school when the Towers were hit. I knew I wanted to do something then. And when it came time to choose college or something else, I wanted to get my hands dirty. It all stemmed from the Towers. I wanted to do my part.”

He’s in the desert as part of a light infantry unit. As he and his team get closer, the insurgents wait.

Ryan Major loves rugby because it’s loud, fast and has lots of crashes. He is hoping for gold at this year’s National Veterans Wheelchair Games.

“We were two or three blocks away and I watched two squads cross that intersection,” he says.

He’s only a couple feet away now.

“I took like five steps … ”

Major steps down with his right leg.

The enemy pushes the remote control.

The bomb explodes with a deafening roar, and fills the air with a lethal mix of fire and shrapnel.

“I was awake for the whole thing,” he said. “I remember going up and facing the stars.”

Major, 22, is blown up and over a steel gate and six-foot concrete wall.

His team, many with shrapnel injuries themselves, jump into their armored Bradley Fighting Vehicle, smash through the concrete and rush him back to the base camp.

“My guy, he had me laying on the floor and he is covering my leg. I’m losing blood like crazy. Trying to go to sleep. He smacks the p— out of me a couple times. I knew I was in a bad situation.”

“Read me my Last Rites. Tell my mom I love her,” Major says to his Soldier.

“No! Wake your b—- ass up! I’m not telling her anything! You’re telling her!”

They make it back to base.

“The surgeons and the doctors, they did their thing. Then they induced me into a coma.”

Doctors cut off his right leg and right thumb in Iraq. An infection while he was still in the coma took his left leg, two fingers on his right hand, his thumb on his left, part of his elbow and forearm.

Major wakes up six weeks later, Dec. 26, in a hospital room inside Walter Reed.

And his nine years of dark depression begins.

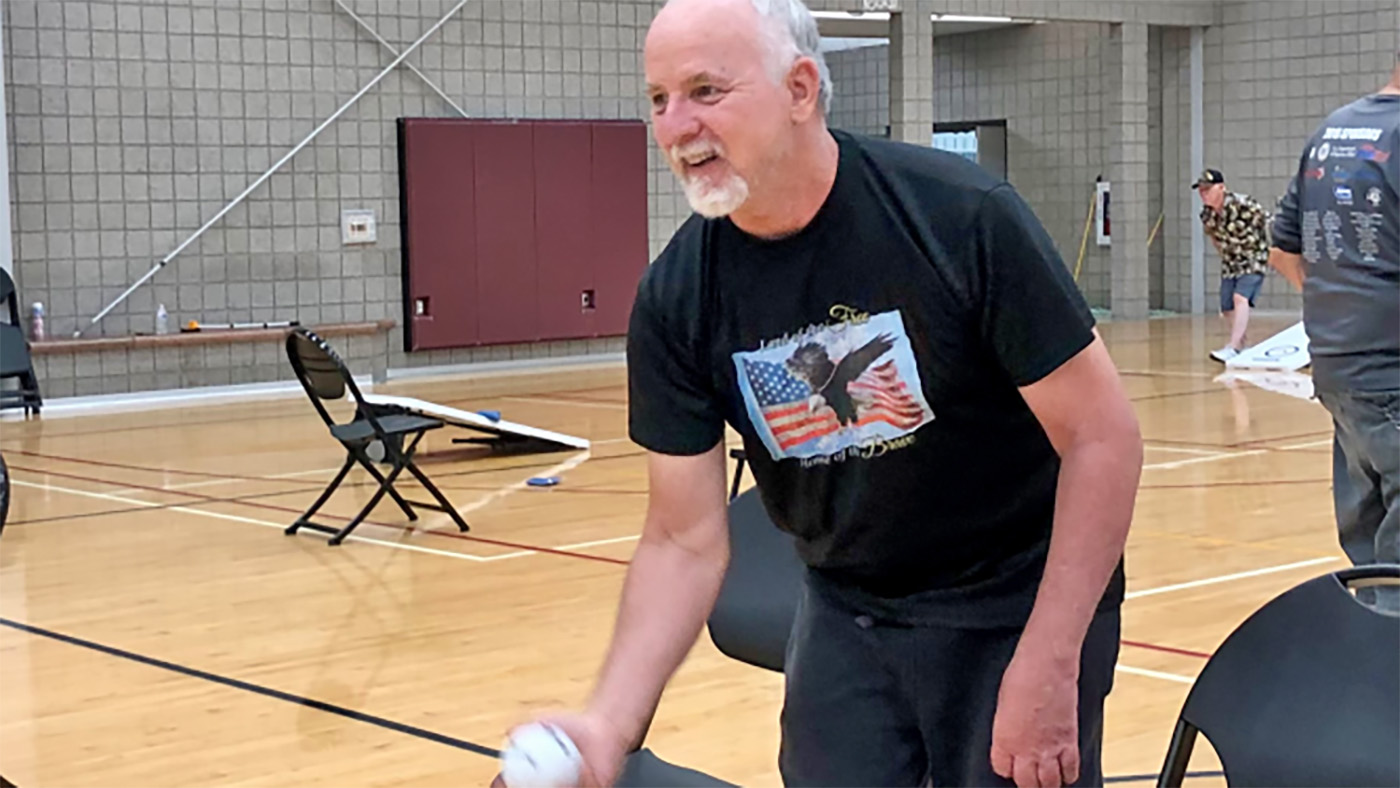

Thirteen years after waking up in that hospital room, Major is one of the most vocal and energetic competitors at the 39th Annual National Veterans Wheelchair Games in Louisville, Kentucky, with quad rugby his favorite sport because it’s loud, it’s fast and there’re lots of crashes and smack talk.

“Hey, it’s sports. I’m a competitor. I was competing in the military. I’m competing still. It’s fast and I like to go fast.”

Major whips around with a white ball in his hand. A wheelchair cracks into him from behind and throws him from the chair and to the ground. He gets helped back in and shakes it off. Another chair crashes into him from the side as Major smacks down on his wheel into a backspin and then scores.

He crosses his arms, leans back his head and howls to the rafters.

“WHOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!”

He makes it look easy, but it wasn’t always this way.

“Dude, it was rough,” he said. “So rough, and I was in a really dark spot. A deep, weird depression. It was a lot of self-doubt and being hard on myself. It’s typical, going from a 100 percent independent man, having to depend on everybody for everything. That took a really big shot to my pride.

“It took me so long. I don’t have my legs. I can’t play football or anything I used to do and love. I used to play football. I wrestled. I did track and field. Now I can’t do any of that.”

Days turned into weeks, months and years.

His mom, Lorrie Knight-Major, said she and his brothers – Michael and Milan – along with Ryan’s friends, rallied to do whatever needed done.

“I credit his brothers, his family and his amazing friends who have been there all the way for him, and for all of us,” Knight-Major said. “To this day, he has a great support system. I wished every Veteran and every person recovering had that kind of love.”

Corey Fick, Ryan’s best friend since the 6th grade, visited him almost every day in the hospital and made him get out and about.

“Everybody was crying when we found out he got hurt, but he is a soldier through and through,” Fick said. “He is a soldier through and through, and whatever his cause, he’ll die for it. There’s no fight he’s not going to win. I think he had a 4 percent chance of making it out of Ramadi alive.

“If this happened to anyone but Ryan, I don’t think they could do what he is doing. He has no fear and is living life to the fullest.”

As Major watched others in a wheelchair living their lives, that’s when he knew he had to do it, too.

“I’m watching other Vets in my situation who had been hurt for a few years. They’re walking and talking and out having fun and I’m overhearing them. Why am I moping around when you got other amputees going out and having the time of their life?

“It was time for me to get my ass out of this bed and start getting active.”

The first thing he did was the Hope and Possibilities handcycle race around Central Park.

“You hear people cheering you and that started to boost me back, but it was easy. I went back to my therapist and said, ‘What’s next?’”

“There’s an Army 10-miler,” the therapist said.

He did it and wanted more. So he did the New York Marathon – 26.2 miles on a hand cycle.

“I went from a 5K to a 10-miler to a marathon all in a year,” Major said. “The best part of a marathon, is all the fans on the side, yelling at you and telling you you’re doing awesome. The worst part of a marathon, in my opinion, are those last two miles. Those last two miles were the longest two miles ever.

“I was hurting bad. My fingers were cramped and locked in place. But I crossed that finish line and said, ‘God, I am a freaking trooper. I am the biggest bad ass in this whole, entire race!”

He hasn’t stopped since.

“I found out I can still do sports. I didn’t ski before I was injured. I had my first skiing experience in Colorado and didn’t anticipate liking that. They had me going down that mountain fast and I fell in love with it. I’m kayaking. I’ll do anything.”

Besides rugby, Major is competing in javelin, table tennis and even bowling this year.

“But I want that gold in rugby,” he said. “That’s the goal. Haven’t gotten it yet. Got close and made it to the final round once. I’ll get it.”

“I am so very proud of him,” his mom said. “I am amazed at the adversity he had to overcome. Ryan has always been a fighter. He wakes up every morning happy, and makes the most out of each day of his life.”

He sometimes thinks back on that day when everything changed, but doesn’t stay in that place too long.

“Those thoughts creep in my head every once in awhile. The what ifs, the woulda, coulda thing. Those are never good,” he said. “There are positives and negatives to every situation. If I wouldn’t have joined the military, wouldn’t have met my brothers in arms, who are a huge part of my life. I never would have had that experience. I never would have traveled. I never would have had those life experiences.

“I still keep in touch with those guys from Walter Reed and with some of the staff. All these years back, and we still talk.”

It’s that brotherhood, he said, that makes these Games so important.

“I like to be loud out there and have fun. Other Vets look at me and that makes them proud. They say it inspires them. Well, they inspire me.”

Major just has one request if you see him on the street. Don’t call him disabled.

“I’m an athlete. And I hope when they look at me, they think I’m a good athlete. That’s what they can call me.”

Topics in this story

More Stories

West Virginia mom builds confidence at the National Veterans Wheelchair Games.

Air Force Veteran Mark Wager overcame a stroke and is now competing in the 2024 National Veterans Golden Age Games.

Clinic offers a wide range of adaptive sports activities tailored to Veterans with physical and mental challenges.

Watching these veterans compete every year is amazing and motivating… I love it….

great spirit of the mayor

Is this another Wheelchair game? I dont get.

Very inspiring story. So many men and women of our Military are coming back wounded like this.

very inspiring. what a determine fellow.