Modern communication affords a service member instant access to family from long distance deployments. But 100 years ago, during World War I, written correspondence was the only way for American soldiers on the Western Front to communicate home.

Even by today’s standards, a written letter holds a touch of intimacy that the buttons of a keyboard cannot match. With limited supplies and only a guess as to when the letter will reach home, the writer carefully chooses each word. Much like a journal or a diary, the writer sends a piece of himself.

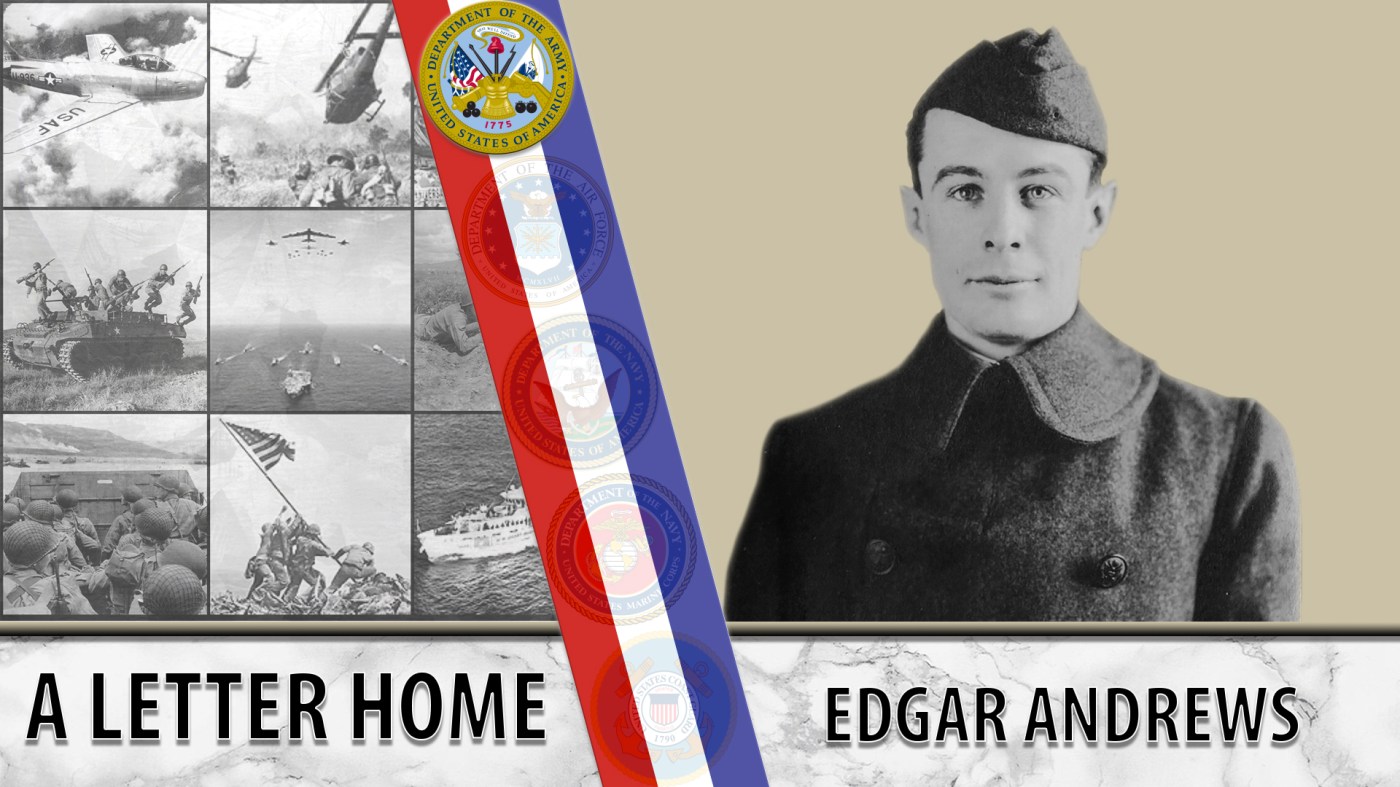

For Edgar Dudley Andrews of Company A of the 102nd Machine Gun Battalion, 26th Division, Massachusetts Army National Guard, writing letters home was personal. Andrews was a Boston local who joined the Army months before the United States declared war on Germany. He would be among some of the earliest American forces to fight in Europe, arriving in October 1917.

The Veteran’s History Project was fortunate to have received 72 pieces of correspondence between Andrews and his family, spanning Jan. 1917 to June 1919. Writing most often to his mother and sister, Andrews’ letters covered a wide range of topics.

One recurring theme was money. He took out war risk insurance to make sure his family would be taken care of in the event that something happened to him while in France. He often wrote about his day-to-day life overseas, though he was mindful of censorship restrictions. It was the farthest he had traveled, and he wrote about how it gave him a fuller appreciation for his home in New England. In other letters, he described the destruction of war on the landscape as “hell itself.” And because of his letters, his parents wrote that they were thinking of buying property in the countryside so that Andrews could enjoy peace and quiet after the war.

In later letters, as the war drew to an end, Andrews confessed to his sister, Sue, that it was easy to become disheartened. Yet he also laughed about his predicament, not because it was funny but because he was still alive. As a machine-gunner, he had been on the front lines. He was happy to be going home alive, glad that he had “done his bit.”

Finding peace

The consistent theme that anchored Andrews’ letters was love for his family. There was an absence of detailed battlefield descriptions because Andrews focused on what was going on at home. Even when things seemed bleak. He often wondered aloud in his writing how much longer the war would go on. His letters show how family got one soldier through the roughest parts of war on the Western Front. From his long days in training and the darkest days of fighting, to a trip to Paris and a stay in the hospital, family is what motivated Andrews to keep going.

Andrews completed his service requirement in 1919, and by 1940 had found the countryside peace his parents sought for him. He later joined the Free Masons and became the Worshipful Master of the John T. Heard Lodge in Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1947.

Edgar Andrews died in 1974. We honor his service.

Contributors

Editor: Michelle Cannon

Fact Checker: Taryn Gehman

Graphics: Kimber Garland

Topics in this story

More Stories

VA recently developed a pilot program providing direct and specialized assistance for the 65 living Medal of Honor recipients nationwide.

This year, Veterans Day ceremonies recognized by VA will be held in 66 communities throughout 34 states and the District of Columbia to honor the nation's veterans.

A personal reflection on generational service from VA Deputy Assistant Secretary Aaron Scheinberg.