Located in Port Huron, Michigan, Lakeside Cemetery Soldiers’ Lot memorializes victims of a July 1832 Asiatic cholera outbreak.

From March to August 1832, the U.S. military engaged Native tribes in the old Northwest Territory during the second phase of the Black Hawk War from 1831-1832. Amid the conflict, a “dreadful cholera scourge” swept through Fort Gratiot, a strategic Army garrison on the St. Clair River.

Brevet-Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott took command of North Western Army in the Territory of Michigan July 3, 1832, and named Surgeon Josiah Everett his senior medical director. Everett’s medical career with the Army began by 1813 and included staff surgeon at the U.S. Military Academy and Fort Monroe, Virginia.

Asiatic cholera was first introduced to North America from vessels arriving from Europe —then via waterways from Quebec, Canada, down to Detroit and Chicago, and at Eastern Seaboard ports. Spread through contaminated food and water, cholera causes severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration. Victims can die in hours or linger for a few days. Lack of sanitation, warm weather, and crowded ships created a welcoming environment for the disease; Fort Gratiot’s locale on the river and increased military presence made it a hotbed for the disease. Many of Scott’s men quickly fell ill. The outbreak is now referred to as the world’s “second cholera pandemic.”

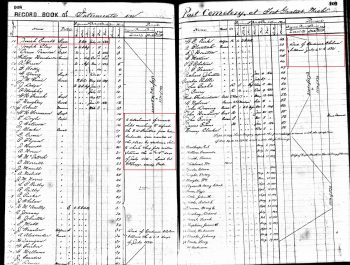

Historically, people buried the Fort Gratiot dead in a post cemetery north of the fort, in the city of Port Huron. Thirty-five victims perished during the two-week epidemic from July 4-18. Buried in the same cemetery, surrounded by a high picket fence, people notoriously called the site “Cholera Point” for some years. Among them was Everett, 43, who died on July 14 or 15. According to an 1890 newspaper article, a now-lost “weather-beaten monument…marked the resting place of the dead soldiers.”

Even before the Civil War, the need for a garrison in southeast Michigan waned. The city benefited from shrinking the military reservation footprint over the next two decades. In June 1860, legislation authorized the Secretary of War to grant Fort Gratiot lands to Port Huron, “a lot not to exceed 30 acres…from the land adjoining the city cemetery” for its enlargement. In March 1873, another law authorized the sale of more reservation land. Despite federal funds and authorities, local action was slow.

Remains moved

The Army moved 136 remains from the post cemetery to a corner of Lakeside Cemetery in October 1881. By then, people could only identify 36 individuals, among them Everett. His grave has an upright private marker typical of the early 19th century. The U.S. government accepted a donation of the less-than-0.2-acre parcel. In doing so, the government agreed to pay the city $30 per year to keep the grounds “well policed” and grass mown. The government abandoned the fort itself three years later; it become a park.

In 1884, Congress approved $3,000 for the installation of a “suitable monument, with headstones, and for curbing or fence” at the Lakeside Cemetery lot “occupied by the bodies of soldiers dying in the service.” The Army selected a design from Port Huron Marble Works, one of the nine bidders. The 23-foot-tall monument was erected by the end of October 1885. It’s flanked by neat rows of graves framed by 12-inch-high stone coping. The Port Huron Times Herald reported that the base, die, and shaft was Concord granite; and the standing U.S. soldier atop the shaft Italian marble. The inscription reads in part: “Among those whose graves cannot be identified are they whose names are inscribed herein, who fell Victims to the Cholera Epidemic, July 4 to 18, 1832.”

Not long after, the city proposed a new water-pumping station near Lakeside Cemetery. A fearful citizen decried the location, citing the potential rise of malaria, scarlet fever, and typhoid fever. “Competent physicians assert that germs of deadly disease are cast loose from the dead bodies…rendering the water below Lakeside [C]emetery unfit for use.” Understanding of the cause and transmission of disease had evolved since the Fort Gratiot cholera epidemic.

Monument’s reminder

The National Cemetery Administration administers Lakeside as one of several historic soldiers’ lots embedded in private cemeteries. The monument reminds visitors that while historic pandemics have taken the lives of service members through the centuries, they will not be forgotten.

Sara Amy Leach is the senior historian for the National Cemetery Administration.

Topics in this story

More Stories

The 80th anniversary of the beginning of World War II's Battle of the Bulge was commemorated at the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. on Monday, Dec. 16, 2024.

VA recently developed a pilot program providing direct and specialized assistance for the 65 living Medal of Honor recipients nationwide.

This year, Veterans Day ceremonies recognized by VA will be held in 66 communities throughout 34 states and the District of Columbia to honor the nation's veterans.