In U.S. wars prior to Desert Storm, military spokespeople would answer questions, then wait for the next day’s newspaper clippings or the nightly news to see developments.

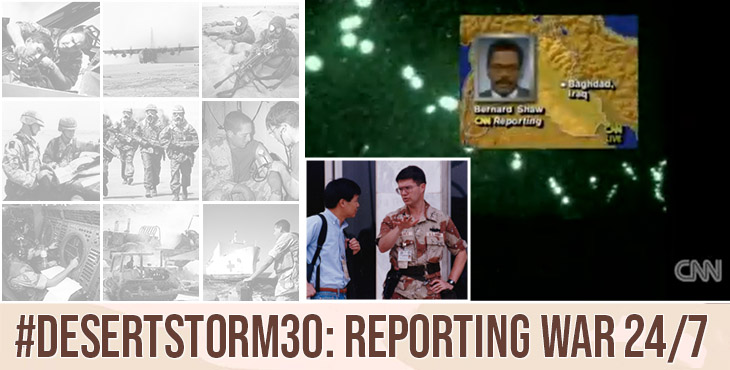

Desert Storm changed that, when reporters broadcast the war as it happened.

View from the top

Army Veteran Colin Powell was the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the time. The retired general was in the Pentagon, where reporters always wanted more information.

“The media wanted to know what’s going on, of course,” Powell said. “And we wanted the media to know. But I couldn’t let them know everything.”

Powell said the public’s right to know is what drove decision making in the Pentagon.

“The media always wanted more than I could send to them,” Powell said. “And I always gave them more than I really want to give them. But we had to do it. I’m a great believer in the First Amendment to the Constitution, and I want to tell the American people everything they deserve to know. These are their young people we’re sending into conflict.”

He said telling the media as much as possible without putting troops at risk was the senior leadership’s goal. He said he knew they were doing a great job when Saturday Night Live started doing skits highlighting the Pentagon’s efforts.

Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Army Gen. Colin Powell brief media members in the Pentagon in January 1991. Department of Defense photo by Robert D. Ward

On the front lines

Army Veteran Bill Mulvey was on the front lines of that war. He was the chief of media relations division for Army public affairs, hand-picked by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs Pete Williams, to lead the Joint Information Bureau (JIB) at Dhahran International Hotel in Saudi Arabia.

The JIB was about 200 miles south of the Kuwait border. The hotel, located right next to a major airfield, was the center of Desert Shield’s media activity. There, the JIB’s members placed reporters into military units.

Ground rules

The media elected their own representatives from hundreds of outlets to work out how they would cover the war. These print, radio, TV and photography representatives formed the media pools. Their jobs were to gather the news and share the footage, written stories, photographs and recordings.

That groundbreaking coverage brought the war into America’s living rooms, 24/7. It was Mulvey, among others, who made it happen.

“One of my main jobs was to bring those ground rules and guidelines to the working media there and work out the details, how were we going to cover this war,” Mulvey said.

Together, they came up with 12 ground rules that became the standard. The rules covered operational security and even became another skit on Saturday Night Live.

Embedding reporters

In various forms, the American press has long covered its wars. For Desert Storm coverage, Mulvey said the military looked to its own history to develop a strategy, harkening back to the days of Walter Cronkite and Andy Rooney with troops during the Normandy invasion June 6, 1944.

One of the keys to reporting Desert Storm stories was the media pools. Because of the unique and vast terrain of the war, reporters needed to travel with the military for wartime operations. Instead of reporters telling a story from afar, they would eat, sleep and move with the military units on the ground.

“You couldn’t just drive your Toyota out across the desert,” Mulvey said. “You had to go with the military.”

Not just any reporter could go out, though. The members of the pools had to be physically fit, and then trained on first aid and how to don protective gear. One journalist cut his 18-year-old beard for his chemical protective mask to seal. A two-pack-a-day smoker quit cold turkey and lost 30 pounds.

At the high point of the war, over 150 journalists embedded within ground units and ships at sea. For diversity of coverage, the pools included each medium of coverage. A section of three TV people—a correspondent, camera person and sound person—along with a radio person, a photographer and two print journalists, became the staple of the war.

Watching the war on TV

About an hour before the air war began, reporters at the JIB noticed that nearly every aircraft at neighboring Dhahran Air Base had left.

“Pretty good indication the air war was about to start,” Mulvey joked. “I knew maybe six hours in advance when the air war was going to start. But I was the only one in the JIB that knew.”

Once the first bombs dropped, Mulvey said he turned on CNN to watch the events.

“Then we had ‘Live from Baghdad’ with Peter Arnett and such,” Mulvey said. “As the bombs are coming in, we saw it live, which was fascinating.”

Mulvey, a Vietnam Veteran, said watching on TV from the JIB (“We were only in the sealed basement during SCUD attacks.”) contrasted greatly from his experience decades earlier. They watched reporters embedded with Air Force units flying into Baghdad and Navy units firing their big guns and Tomahawk missiles. Never before had viewers – or even the military not on the front lines – watched live attacks, like the reports of incoming Scud missiles.

Mulvey said they nicknamed those reporters reporting from outside the JIB during SCUD attacks “canaries.”

“We knew if they fell over that we probably didn’t want to go out of the sealed basement,” he said.

The Doonesbury comic strip talking about reporters performing physical fitness tests, signed by creator Garry Trudeau.

Logistical challenges

Getting the pools’ written stories, videotapes, radio recordings and rolls of film back to the media bureaus at the JIB became a logistical challenge. The military flew the reports from King Khalid airport back to Dhahran on media flights, arriving at 10 p.m. daily.

The JIB also reviewed any questionable content for adherence to the ground rules. Most of the time, there were no disagreements between the journalists on the ground and the military’s public affairs officers with them.

Of the 1,351 written pool reports, only five stories came back needing Pentagon clearance. Four cleared as written, but one was cleared only after the civilian editor made changes.

“The changes were somewhat extensive because it gave away the ‘left hook’ maneuver that we were doing,” Mulvey said. “It located way out in the west the tactical plan that we were executing, and we didn’t want Saddam to know we were that far west.”

Lessons learned

As a company commander in Vietnam, Mulvey said he didn’t see a single journalist during his year-long tour. He said Desert Storm changed the relationship between military and the media.

“A lot of members of the military who were very skeptical or – more than that – anti-press or anti-media realized they had a story to be told and the press could do a pretty good job of it,” Mulvey said. “I think we developed a lot of trust and confidence across the board, at the general officer level, at the battalion or brigade commander level and on down to the company commanders. On the other side of that coin, I think the members of the news media developed a great respect for our military, which they hadn’t had before that. That spread throughout the news media.”

Embedded into the military units, the journalists talked directly to soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines and Coast Guardsmen. This closer reporting made the stories feel more personal, and they hit closer at home.

“The better they [journalists] know the unit, the better they are going to report with the unit,” Mulvey said. “The longer they’re with them, there’s a building of camaraderie.”

Despite the immediacy of live broadcasts and the wide-spread coverage, reporting the war was not a one-size-fits-all model.

“Desert Storm was very unique,” Mulvey said. “I don’t think we can look at Desert Storm as a model for the future. It was a culmination of the past. We learned.”

Listen to the interview

Links:

https://www.cnn.com/2016/01/19/middleeast/operation-desert-storm-25-years-later/index.html

https://www.c-span.org/video/?20122-1/television-coverage-operation-desert-storm

Topics in this story

More Stories

Summer Sports Clinic is a rehabilitative and educational sporting event for eligible Veterans with a range of disabilities.

Report examines the input of over 7,000 women Veterans: They are happier with VA health care than ever before.

Veterans and caregivers, you can help shape the future eligibility requirements for the VA Caregiver Support program.