Steve had come to a fateful crossroad. An argument with his wife Jenn had escalated. He and Jenn had their share of arguments in the past, but this felt different – scarier. Things had gone too far this time. She was outside the house, calling 911.

“It was the realization that I just screwed everything up,” Steve said. “Everything.”

He remembered taking walks in the past to cool off after stressful situations. He slipped on his shoes and headed out. Before he got to the next driveway, the police were there. And Steve knew it was for the best.

“They told me what to do and I did it,” he said. “I told them, ‘I don’t want to be alive. I don’t know what I’m doing anymore.’”

He was placed in solitary confinement and assessed by psychiatrists. Sitting alone gave him plenty of time to think.

An officer came by with a cart full of books and he chose one at random. He read it, cover to cover, over the next six hours.

“It was, eerily enough, about exactly what I was going through, handling your temper, finding yourself, treating your family right,” he remembered.

“I went to VA. What do I need to do?”

When he was released the next day, Steve couldn’t go home. He had a restraining order against him from having contact with Jenn. The next few months were spent couch surfing with friends and figuring out how to fix his life.

“I didn’t wait for the court or for anything to tell me, ‘You need to start getting help,’” he said. “I went to VA and said, ‘What do I need to do right now?’”

The answer: Get treatment for his medical and mental health needs and address his pending legal problems with the help of the Veterans Treatment Court.

Veterans Treatment Court allows qualified Veterans to minimize, or get dismissed, legal charges against them by addressing the problems that led to run-ins with the law. Often, this includes substance abuse problems or mental health issues.

“Veterans Treatment Court takes a non-traditional approach to the criminal justice system,” said Judge Cynthia Davis, who oversees the court in Milwaukee County.

“We focus on treatment rather than punishment,” said Michelle Watts, Milwaukee VA social worker. “It’s not that punishment doesn’t exist. It’s just not the first response.”

Participants are typically those charged with non-violent crimes, according to Jake Patten, court coordinator. “When agreeing to enter the court, Veterans plead guilty, accept responsibility for their actions and are then overseen by a team led by Judge Davis,” Patten said.

Milwaukee County has 78% graduation rate

Stringent rules and benchmarks are laid out and missing just one can lead to either a restart or dismissal from the program.

The path isn’t easy and not every Veteran who takes part graduates. It can take anywhere from six months to two years to meet all the requirements.

Milwaukee County’s VTC boasts a 78-percent graduation rate and officials credit that to the team approach and evidence-based practices that are employed.

“Revocation is pretty rare,” Patten said. “Our team really works with all the participants to succeed in this program.”

“I’ve seen many people turn their lives around,” Watts added. “Veterans Treatment Court really does give second chances.”

Steve got that second chance.

PTSD, alcohol, drugs

After Steve was charged, his lawyer suggested that he might qualify for VTC.

VA and VTC personnel were working to get Steve in the program. And when they did, Steve made sure the opportunity didn’t pass him by.

“I’m one-million percent appreciative and grateful I was accepted into the treatment court,” he said.

Going before Judge Davis the first time was nerve-wracking. Steve remembered answering a yes-or-no question from Davis with a babbling response.

“And she said, ‘Stop. That’s a very lawyerly answer of you, but it’s a yes or no.’ At that point, I laughed at myself. And then it was easy,” he said.

The court laid out Steve’s plan, which he had already gotten a jump on thanks to the Milwaukee VA, including enrollment in the Outpatient Addiction Therapy program and dialectical behavior therapy.

The Army Veteran learned he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder related to his work in field hospitals in Iraq and Afghanistan. His job was triaging wounded soldiers, many of whom were severely injured by roadside bombs and other explosives.

In addition, he was struggling with alcohol and prescription drug use. The result: He became withdrawn and combative.

“He was very short-tempered and slept a lot,” Jenn remembered. “In general, he was not very happy… and in a shell.”

Clean and sober fairly quickly

The court and VA set up a plan for Steve that included treatment for his PTSD and substance abuse problems, including community service, counseling, therapy and random drug testing.

He was able to get clean and sober fairly quickly but had to work on mental aspects of his treatment.

He learned that it’s normal to feel two conflicting emotions at the same time and that he didn’t have to win – or even fight – every little battle.

“I used to argue about everything,” he said. “My thing was trying to prove a point. And now, I don’t have to prove anything to anyone. I can shrug stuff off now.”

At first, Steve was required to see Judge Davis every month. But as he continued to progress in the program, the court visits lessened.

“I never had a hiccup,” he said. “And then Judge Davis said, ‘The next time I’m going to see you is graduation day.’”

Judge was proud and impressed

When the day came, Steve was nervous.

“I could feel my heart beating in my chest,” he remembered. “And then Judge Davis starts talking about how proud she was and impressed with how well I did. Then she came down and handed me my graduation certificate. Then everyone was applauding.”

Since then, Steve has found himself handling difficult situations in a different way, and Jenn has learned how to help him work through any problems.

“There’s been a couple of times where I was in tears because I was so angry or frustrated,” he said, remembering he used to let such situations fester without talking it out. “But the first time that happened, right away I was talking to her. We just sat and talked and worked it out.”

Steve said he understands what he needs to do to maintain his stability, and he’s thankful for the Veterans Treatment Court. “It treated me like a human,” he said.

“You have to want it. Do it!”

“They’re there to help,” he said. “And that was proven to me on day one. They’re not there pointing a finger at you saying, ‘You screwed up.’ Instead, it’s ‘You messed up. This is what we need to do to help you.’”

Even though he recognized he needed help before he entered VTC, Steve said he couldn’t have succeeded without the court, that it likely kept him out of jail.

“If not for the VTC, I don’t think I would have gotten the mental health treatment I needed,” he added. “The VTC is not easy. You have to want it. Do it. Do what you’re asked or do it better. Listen to what they have to say to you. They help you get a plan.”

Topics in this story

More Stories

Bob Jesse Award celebrates the achievements of a VA employee and a team or department that exemplifies innovative practices within VA.

The Medical Foster Home program offers Veterans an alternative to nursing homes.

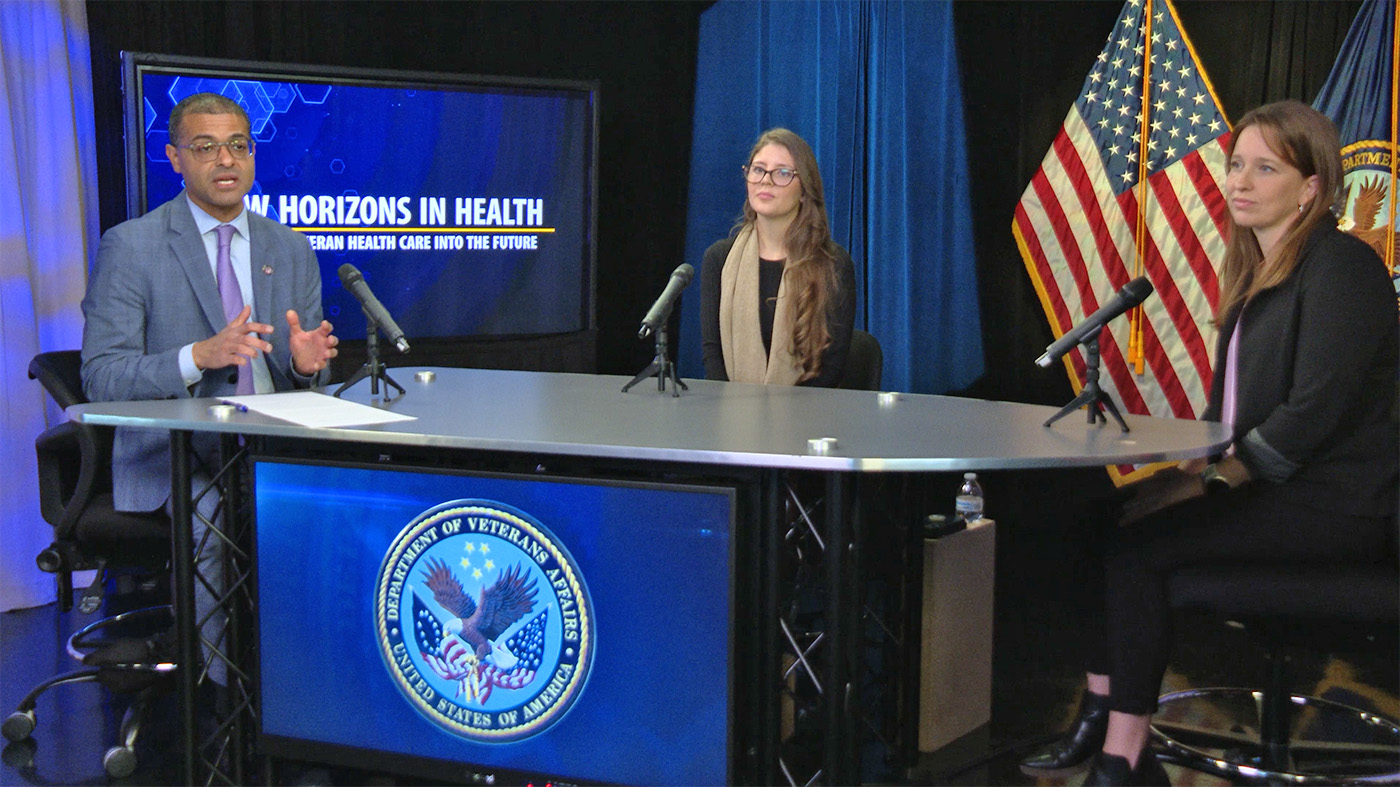

Watch the Under Secretary for Health and a panel of experts discuss VA Health Connect tele-emergency care.