Seventy-eight years ago on April 9, 1942, U.S. forces surrendered to the Japanese on the Bataan Peninsula on the Philippine island of Luzon in World War II. The Japanese subsequently rounded up about 75,000 American and Filipino troops to make a tortuous march to prison camps.

In the “Bataan Death March,” the prisoners trekked 65 miles in brutally hot conditions from Mariveles on the southern end of the Bataan Peninsula to San Fernando. It’s believed that thousands of troops died due to starvation, dehydration and the sheer brutality of their Japanese captors, who bayoneted those too weak to walk.

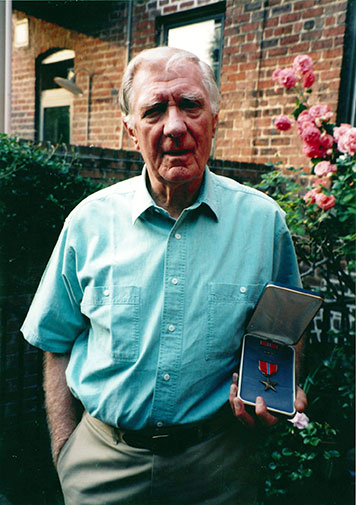

Marine Pfc. Irvin Scott earned medals for his heroic service in World War II, including a Bronze Star.

Marine Pfc. Irvin Scott survived one of the greatest war-time atrocities, as well as three more years in captivity, before he was liberated in 1945. In an interview 50 years later, he remembered the brutality of the Bataan Death March all too painfully. He witnessed tanks and trucks running over his comrades and men getting their heads chopped off and others crucified, with bayonets driven through their hands and rib cages. “We walked over men who were a few inches thick,” Scott said.

`You couldn’t imagine the horror’

Following the march, Scott and other survivors traveled by rail to prisoner-of-war camps, where thousands more POWs died from disease, mistreatment and starvation. Scott ended up in a former Philippine army training center called Camp O’Donnell, where he stayed for about a month. He and other prisoners who had maintained a semblance of strength buried men in mass graves.

“I was one of only three men in the whole barracks who was able to work, and I worked all day digging graves,” Scott said. “We dug a continuous grave and carried men and put them in [the grave]. We could dig them only about three feet deep. Usually, I wouldn’t get three hours of sleep. That’s what life was, but it was a hell of a lot better than the [men] I was carrying out dead. You couldn’t imagine the horror of the g*ddam place. It was unreal.”

From there, Scott and some 200 other U.S. prisoners were ordered to finish building a road the Americans had started in Tayabas on the southern end of Luzon. Tayabas is in the jungle, where heat, rain and mosquitoes combined to make it a prime area of malarial infestation during the war. Scott eventually came down with malaria. Malnourished and weak, he passed out on the road that was being constructed.

A compassionate Japanese guard

In an act of heroism, Bill White, another American prisoner whom Scott did not know, tried to force-feed Scott lugua, a watery rice mixture the prisoners made in a wheelbarrow. While on duty, a compassionate Japanese guard who had secretly left food for Scott slipped him some more food, as well as part of his ration of quinine, a medication that is used to treat malaria. White, who had a milder case of malaria, gave all of his quinine to Scott. One afternoon, White told Scott to keep an eye on the guard.

“This Japanese guard came walking across the rocks,” Scott recalled. “All the prisoners were lying out on the rocks, dying or barely able to move with malaria and dysentery. As the guard passed by, he dropped a banana leaf. He kept walking, didn’t say anything. Bill unwrapped [the leaf], and in it was rice with some other stuff. I don’t know what it was. Sometimes there would be a banana in there. Bill pulled out a little piece of paper that was wrapped around two tablets of quinine.”

Prisoner regains his strength

The noble actions of White and the guard helped Scott regain his strength. He remained in Tayabas until August 1942, when Japan’s empire, which stretched from the Netherlands East Indies to parts of the Aleutian Islands, was at its peak. He later worked for two years at Nielson Field, a Japanese-captured U.S. Army base near the Philippine capital, Manila, before sailing to Japan aboard one of the Japanese “hell ships.” In a POW camp about 60 miles west of Hiroshima, he worked 12 hours daily in a coal mine. Allied forces were then recapturing Pacific islands and moving closer to Japan, while American bombers were hitting cities on the Japanese mainland.

“There was a constant hum as the flights went over, so we knew [the Americans] were bombing all over the place,” Scott remembered. “At night, Navy planes would fly over, then often in the morning the fighter planes from ships would get into dogfights. Things were happening, and we knew the Americans were close.”

The atomic bomb

Early on Aug. 6, 1945, Scott heard a loud rumble from shock waves that were hitting the mountains and bouncing back and forth. The first atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. Three days later, a second atomic bomb destroyed Nagasaki. Soon after, the Japanese forces surrendered, and Scott was a free man. He was 23, weighed 98 pounds and stood 5 feet, 11 inches, one inch shorter than when he had volunteered for the Marines in 1940.

Despite the hardships he endured, Scott came to accept the Japanese people as good human beings. Unlike a friend from the Bataan Death March who despised anything Japanese, Scott felt comfortable driving a Honda Accord in the 1990s that was tagged paradoxically with the license plate “P.O.W.” He knew of other U.S. Veterans who refused to let go of their hatred for the Japanese. One referred to all World War II Japanese soldiers as “pigs,” despite knowing that the guard helped save Scott’s life.

“That comment is probably from a man who will likely go to his death hating the Japanese,” surmised Scott, who was honored with the Purple Heart, the Bronze Star and the Prisoner of War Medal. “I don’t understand why he wouldn’t realize the compassion the individual Japanese guard showed to a prisoner. It was a very personal thing. It was one person reaching out to another.”

Topics in this story

More Stories

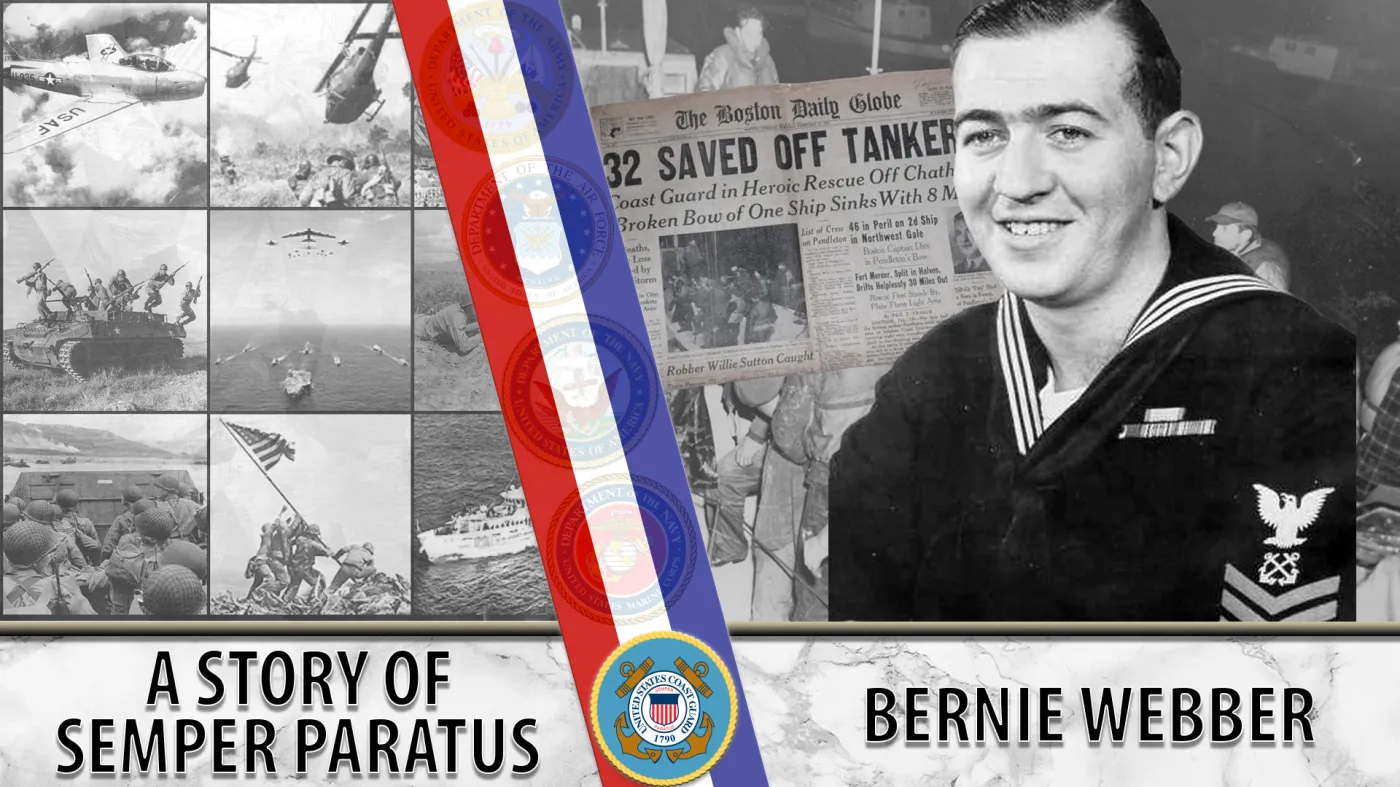

Bernie Webber led one of the greatest Coast Guard rescues in history that was later chronicled in the book and movie, “The Finest Hours.”

As the events of 9/11 unfolded, Marine Veteran Robert Darling served as a liaison between the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney in the underground bunker at the White House.

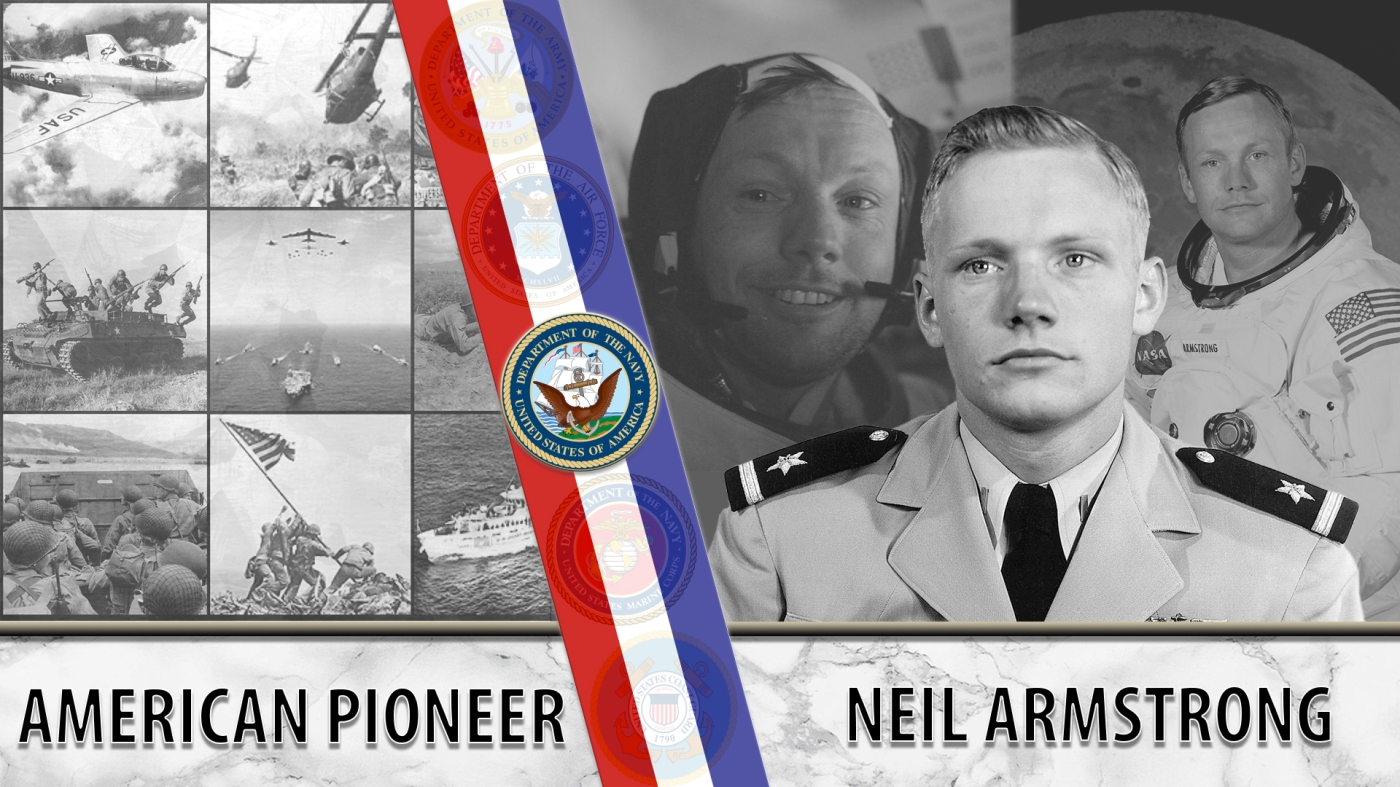

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon. He was also a seasoned Naval aviator.

My father-in-law was part of the army that released these prisoners and saw first hand much of what we see in pictures. He lost buddies as he continued the island hopping until he was wounded and sent home. He carried a lot of bitterness with him also. My wife and I many years later took some young Japanese students into our home. It took him some time but he finally was able to welcome them into his home. I admired him deeply for that act of forgiveness.

Truly an amazing story! I am curious what happened to that Japanese guard. I wonder if anybody knows?

That was a great story. A recent John Gresham book referenced in detail the things of which Irvin Scott spoke. My father was a crew member on board the USS New Jersey thru out WWII. He never expressed his feelings about the Japanese, however; in his war journal one of his statements comes to mind, “ They weren’t really ‘yellow’ at all.” A reference to their skin color. My family and I spent just over 3 1/2 years on Okinawa in the early 80’s. We loved our tour there. As generations move forward events, good and bad, fade away but we should “ never forget.”

As a former Marine I always am pleased to read about people like Irvin Scott and other survivors

From any POW’S God bless each and every one of them

My Uncle was a survivor of the Bataan death march. He despised the Japanese very much the rest of his life.

I was overwhelmed reading this about a virtually unknown American, but a real hero among us.

What an amazing article about an awesome Marine. Although he survived numerous instances of brutality and deprivations, his “Will to Live” was stronger than his sufferings.

Irvin Scott was able to forgive the Japanese people and actually embrace them. Almost the same way the Japanese forgave the Americans.

The simple compassion of one Japanese soldier did not change the world, but it did change Irvin Scott. If this doesn’t help restore your faith in humanity, I di not know what will.

LCDR Larry Kimbrow

United States Navy (Ret))

What a beautiful story. We are indebted to those who served our nation. We are eternally proud and grateful.

“Lest We Never Forget…”