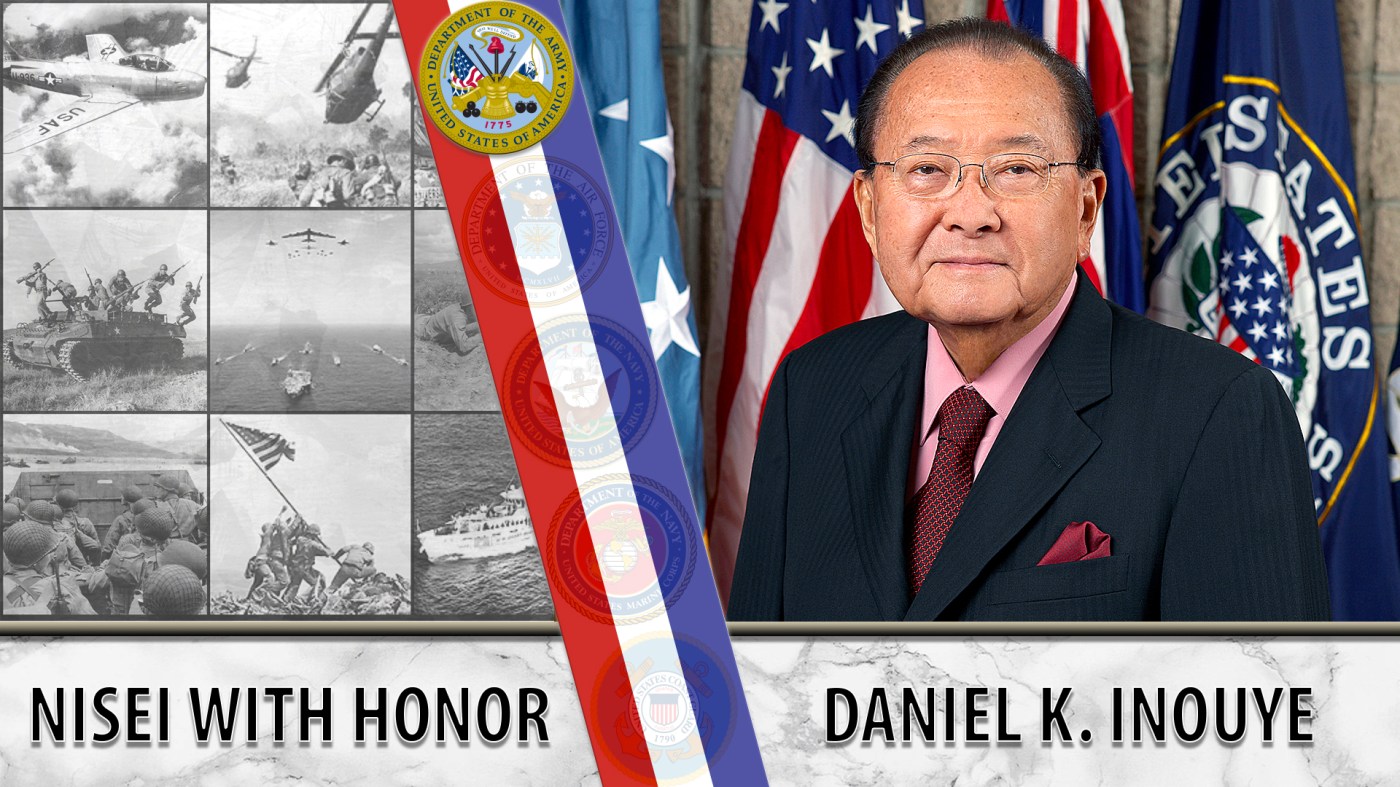

Daniel K. Inouye served during World War II in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in Italy. After the war, he became a lawyer and was active in Hawaiian politics, becoming the state’s first representative to the House and then a U.S. senator.

Daniel K. Inouye was a Nisei – the American-born son of Japanese immigrants. His parents emigrated from Japan to settle in Hawaii’s Bingham Tract, a Chinese-American enclave in Honolulu. As a teenager, Inouye worked for the Red Cross and wanted to attend medical school. That changed when Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941.

As a medical aide with the Red Cross, Inouye was among the first to treat the wounded. When he graduated from high school, Inouye applied to enlist in the military but was denied entry because of his race.

“Here I was, though I was a citizen of the United States, I was declared to be an enemy alien and as a result not fit to put on the uniform of the United States,” Inouye recalled.

When the U.S. entered the war, Inouye and his comrades unsuccessfully petitioned the government to allow Japanese-Americans to join the military. A year later when the Army dropped its enlistment ban on Japanese Americans in 1943, Inouye told his family he had enlisted.

“My father just looked straight ahead, and I looked straight ahead, and then he cleared his throat and said, ‘America has been good to us. It has given me two jobs. It has given you and your sisters and brothers education. We all love this country. Whatever you do, do not dishonor your country. Remember – never dishonor your family. And if you must give your life, do so with honor.’ I knew exactly what he meant. I said, ‘Yes, sir. Good-bye.”

After basic training, Inouye joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, composed of Japanese-American volunteers from the internment camps, Hawaii and states outside of the West Coast exclusion zone. Inouye earned the rank of sergeant within his first year of service and later became a platoon leader. In 1944, the 442nd deployed to Europe and participated in the Rome-Arno campaign in central Italy. In the summer of 1944, Inouye’s regiment transferred to France and moved to the Vosges Mountains. It was here that the 442nd went to rescue the “Lost Battalion” of 400 U.S. infantry during the fall of 1944. For his courage, Inouye was commissioned to second lieutenant.

In April 1945, the 442nd deployed to the Gothic Line in the Apennine Mountains bordering Italy and France. On April 21, Inouye led an assault on a heavily defended ridge known as Colle Muscatello, near the town of Terenzo, Italy. Despite the heavily fortified ridge and Inouye’s injuries, he continued to lead his troops forward, hurling two hand grenades into the enemy position. However, a rifle grenade struck and severed his right arm. Despite heavy blood loss, Inouye tossed a grenade into the bunker and destroyed it. He continued to operate his Thompson submachine gun against further resistance before being wounded in the leg and losing consciousness.

After recovering from his wounds, Inouye honorably discharged as a captain on May 27, 1947. For his service during the war, Inouye earned numerous medals, including a Distinguished Silver Cross, Bronze Star and the Purple Heart.

Post service

After leaving the military, Inouye returned to the University of Hawaii and pursued studies in government and economics. He graduated in 1950, then entered George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C., where he earned a law degree in 1952. After returning to Hawaii, he practiced law and served as Deputy Public Prosecutor for the City of Honolulu. In 1954, Inouye was elected to the territorial legislature and later to the territory’s Senate. Hawaii became the 50th U.S. state in 1959. Inouye was elected to serve as Hawaii’s first U.S. Representative and became a U.S. senator in 1962.

Continuing service

In office, Inouye championed racial equality and Veterans’ rights. In 1981, he proposed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, which led to the 1988 Civil Liberties Act providing redress to Japanese Americans affected by internment during World War II. He also supported the naturalization of Philippine Veterans of World War II as U.S. citizens.

In 2000, the Distinguished Service Cross awarded to Inouye and 21 other Asian-American heroes of World War II received an upgrade to the Medal of Honor to recognize their service in the 442nd Regimental Team.

Inouye died in December 2012. He was 88. He was buried with honors at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii. In 2013, he posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 2019, a naval destroyer was named the USS Daniel Inouye to honor Inouye’s service.

Author: Michaela Yesis

Editor: Sarah Concepcion

Fact Checkers: Adeline Sov and Vivian Hurney

Graphics: Michelle Zischke

Topics in this story

More Stories

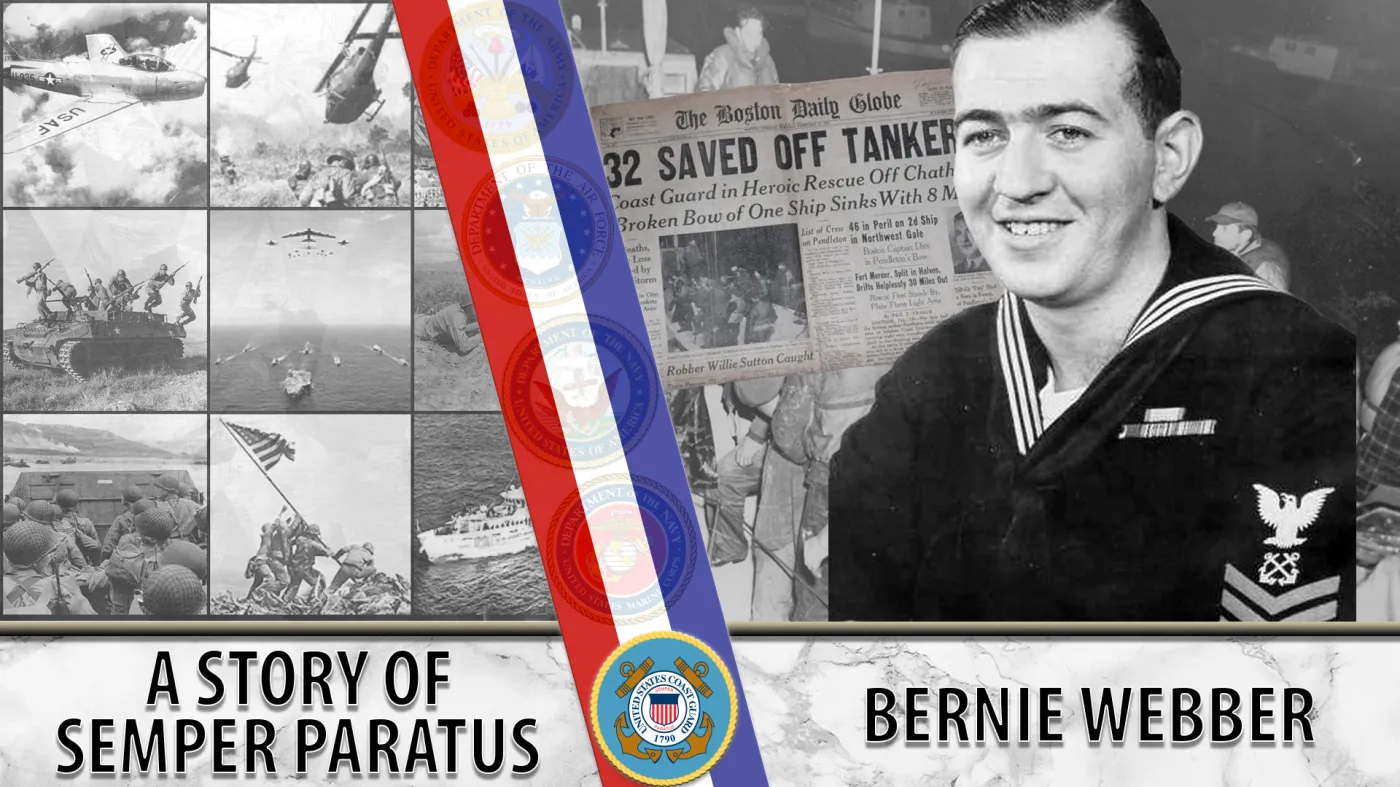

Bernie Webber led one of the greatest Coast Guard rescues in history that was later chronicled in the book and movie, “The Finest Hours.”

As the events of 9/11 unfolded, Marine Veteran Robert Darling served as a liaison between the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney in the underground bunker at the White House.

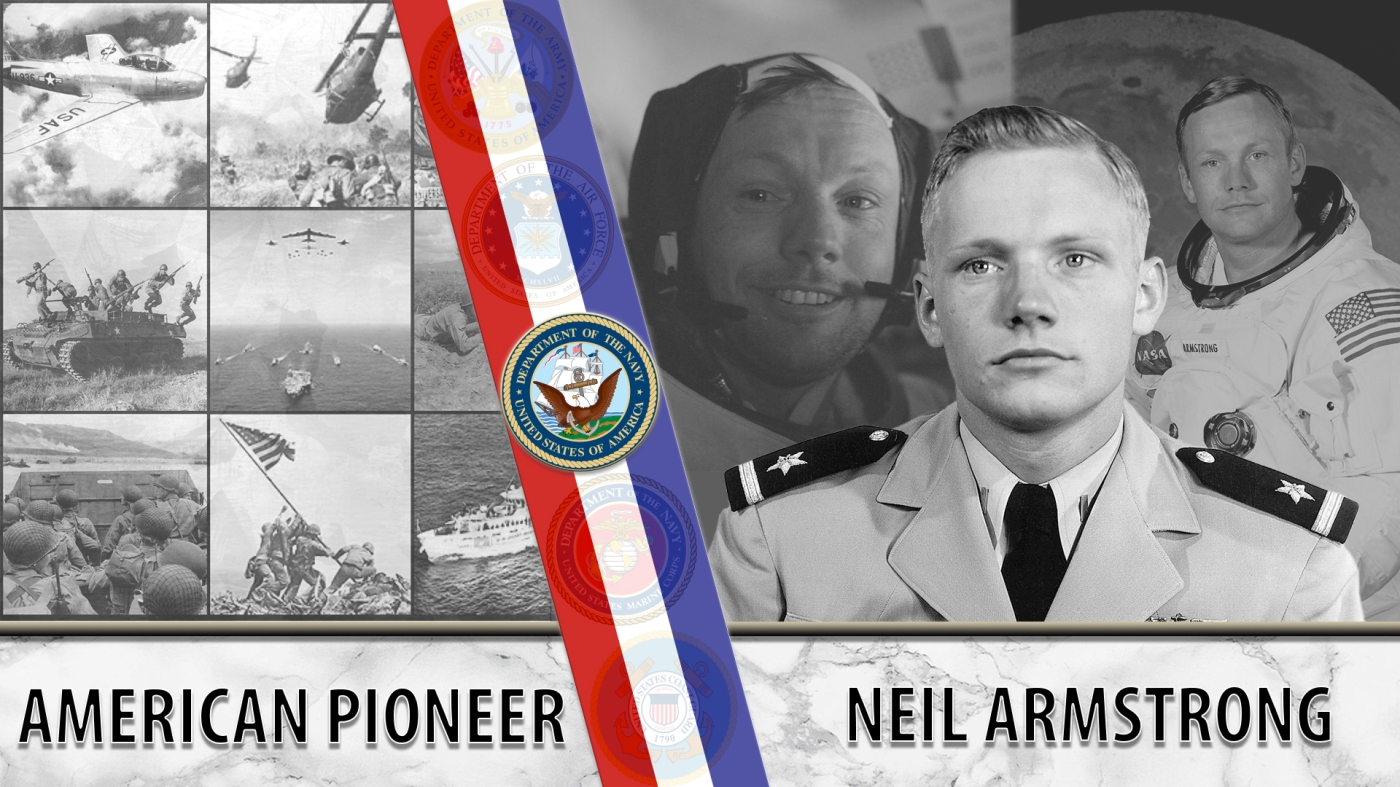

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon. He was also a seasoned Naval aviator.

We honor the service of Daniel K. Inouye.

This is an excellent article about Daniel Inouye and the 442nd RCT; however, the story of the Nisei soldiers is incomplete without mentioning the vanguard of Japanese American combat units, the 100th Infantry Battalion, that was formed by 1,400 men of the Hawaii National Guard in June 1942. Its superior training record at Camp McCoy was cited as one of the reasons for President Franklin Roosevelt to authorize the formation of the 442nd in January 1943. The unparalleled combat record of the 100th Infantry Battalion in Italy starting from September 1943 convinced the War Department of the trustworthiness and bravery of the Nisei soldiers, which led to the eventual deployment of the 442nd RCT in June 1944. Mahalo! https://encyclopedia.densho.org/100th%20Infantry%20Battalion/