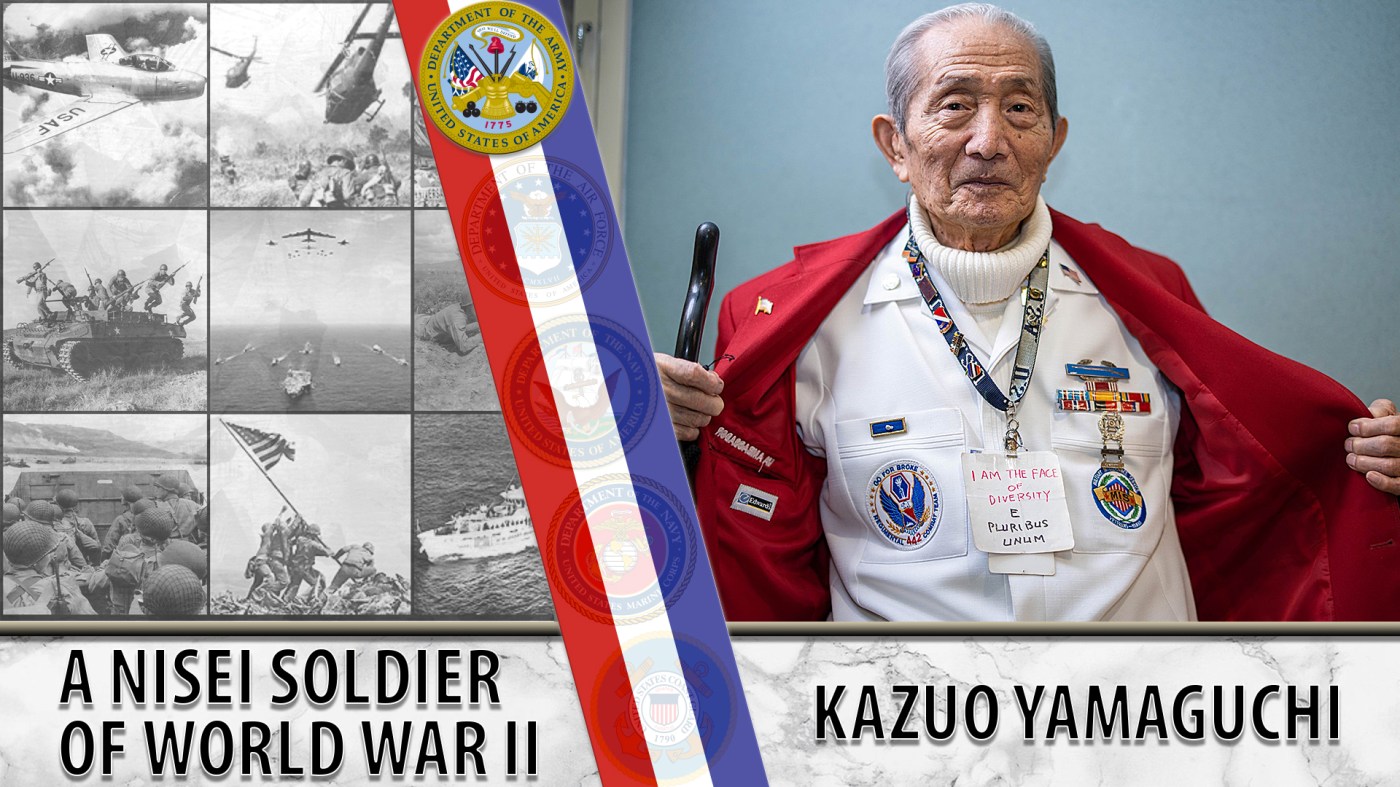

As a second-generation Japanese-American citizen, Kazuo Yamaguchi wasn’t allowed to enlist to fight for his country. He was soon drafted, and fought honorably in WWII.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Kazuo Yamaguchi felt a sense of patriotic duty to serve the country that had provided him and his family a prosperous life. It was his father who said to him, “Kazuo, our country, the United States, has been good to us.”

Yamaguchi went to a recruiting station after graduating from John Adams High School in the Ozone Park neighborhood of Queens, New York City. However, because he was a second-generation Japanese American, the U.S. Army rejected him over concerns of potential allegiances to a foreign government. “How the hell can I be an enemy alien if I was born in Long Island City?” Yamaguchi recalled telling recruiters at the time. “I was naive.”

Scathed by this rejection, Yamaguchi moved on with his life and attended the University of Connecticut to study agriculture. But before he could complete his first year, he received a draft notice. He soon reported to Camp Upton, in New York, for basic combat training.

At Camp Upton, more than 1,000 New York-based Japanese American citizens were imprisoned in the internment camp there. Yamaguchi wasn’t sent to the internment camp, he was assigned to a segregated unit for Japanese American soldiers.

Yamaguchi would become a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team – the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history. Yet, born and raised in the United States, Yamaguchi still felt like he was under constant scrutiny due to his heritage. He and his fellow Japanese Americans faced challenges regarding their identity and loyalty by the same country they were risking their lives for, regardless of their accomplishments.

“They didn’t trust me,” said Yamaguchi. “Wherever I was assigned, they wanted to see my identification card.”

Yamaguchi recalled one moment where he and his fellow Japanese Americans earned the respect of his entire unit. He was aboard a troop carrier when it was being held up in Tokyo Bay by a flotilla of deadly mines. The ship’s gunners were unable to defeat the obstacle, even with their five-inch cannons. The situation appeared doomed until Yamaguchi and other Japanese Americans, using only their rifles, successfully cleared a path, saving everyone on board.

By the time Yamaguchi arrived in Tokyo, the U.S. had dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, forcing Japan’s surrender. Following the bombings, the Army assigned Yamaguchi as a translator with the Military Intelligence Service, after they found out he was bilingual and well versed with Japanese culture.

Once on Japanese soil, and no longer an enemy combatant, Yamaguchi felt a responsibility to help mend the destruction. His efforts stalled once he realized how the conflict between his ancestry and home country made it impossible for the Japanese people and him to relate.

“There were Japanese people who hated us. They’d say, ‘You’re ethnically Japanese. Your parents are from Japan. You’re in an American uniform as MIS – what’re you doing here? You’re a traitor,’” he said.

To make amends, Yamaguchi and others tried to help orphaned Japanese children wandering the streets. “We would bring these kids in and give them a bath, they were full of lice and their clothes were falling off,” said Yamaguchi. “When we went to the mess hall to get extra food, we were told to not give aid and comfort to the enemy.”

He soon found middle ground between himself and the people of Tokyo by discussing appreciation for his heritage and family values, like duty and honor.

After the war

After leaving the Army, Yamaguchi sold ornamental plantings for gardens. He continued to defend basic humanity and fought for the rights of individuals to live with dignity. For his service, Yamaguchi received the Congressional Gold Medal.

At 94 years old, he still deals with PTSD. Despite his struggle, Yamaguchi manages to drive himself from New Jersey to the Northport Veteran Affairs Medical Center in New York once every week to volunteer.

“My responsibility is to teach these young Veterans something very important,” he said. “I want to teach these young Veterans to care. Caring sounds simple but, no, to care is very deep. That feeling of caring comes from the heart… I try to keep race out of it, it has nothing to do with race. It has everything to do with being a human being. That’s my responsibility.”

*Editor’s note: Sources for quotes and portions of this story come from Discovernikkei.org and the NYDailyNews. Photo for the image above via the Northport VAMC.

Writer: Rachel Heimann

Editor: Michaela Yesis

Fact Checker: Richard Aguilera

Graphics: Michelle Zischke

Topics in this story

More Stories

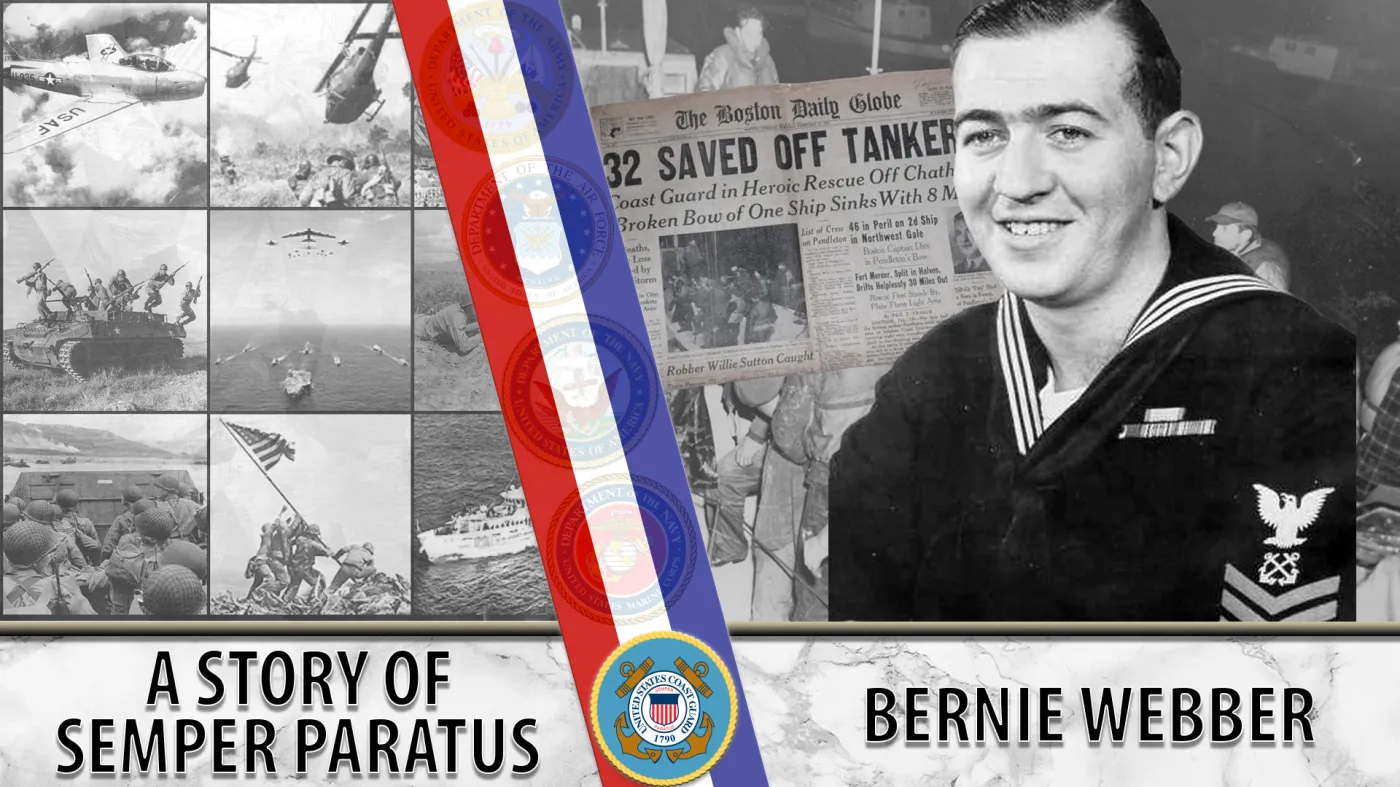

Bernie Webber led one of the greatest Coast Guard rescues in history that was later chronicled in the book and movie, “The Finest Hours.”

As the events of 9/11 unfolded, Marine Veteran Robert Darling served as a liaison between the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney in the underground bunker at the White House.

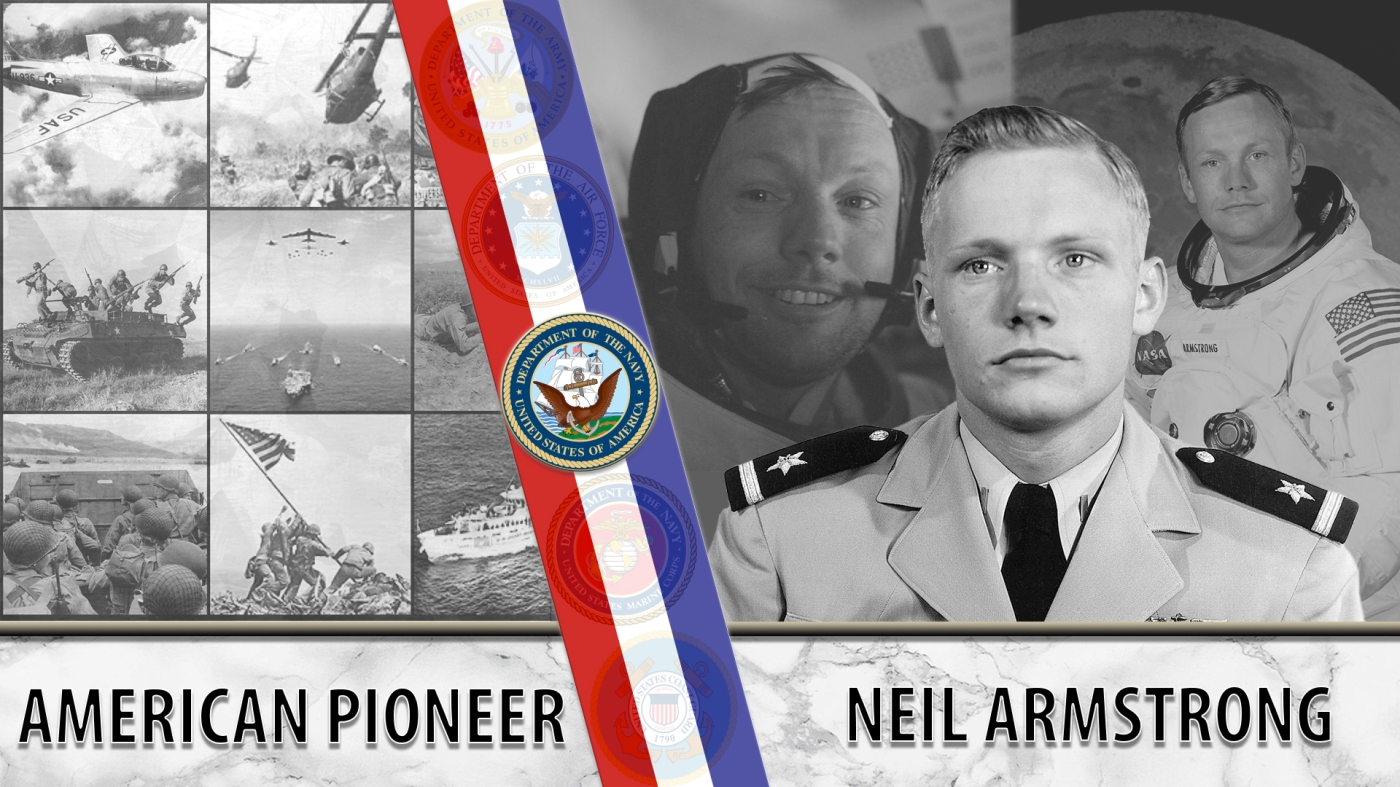

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon. He was also a seasoned Naval aviator.