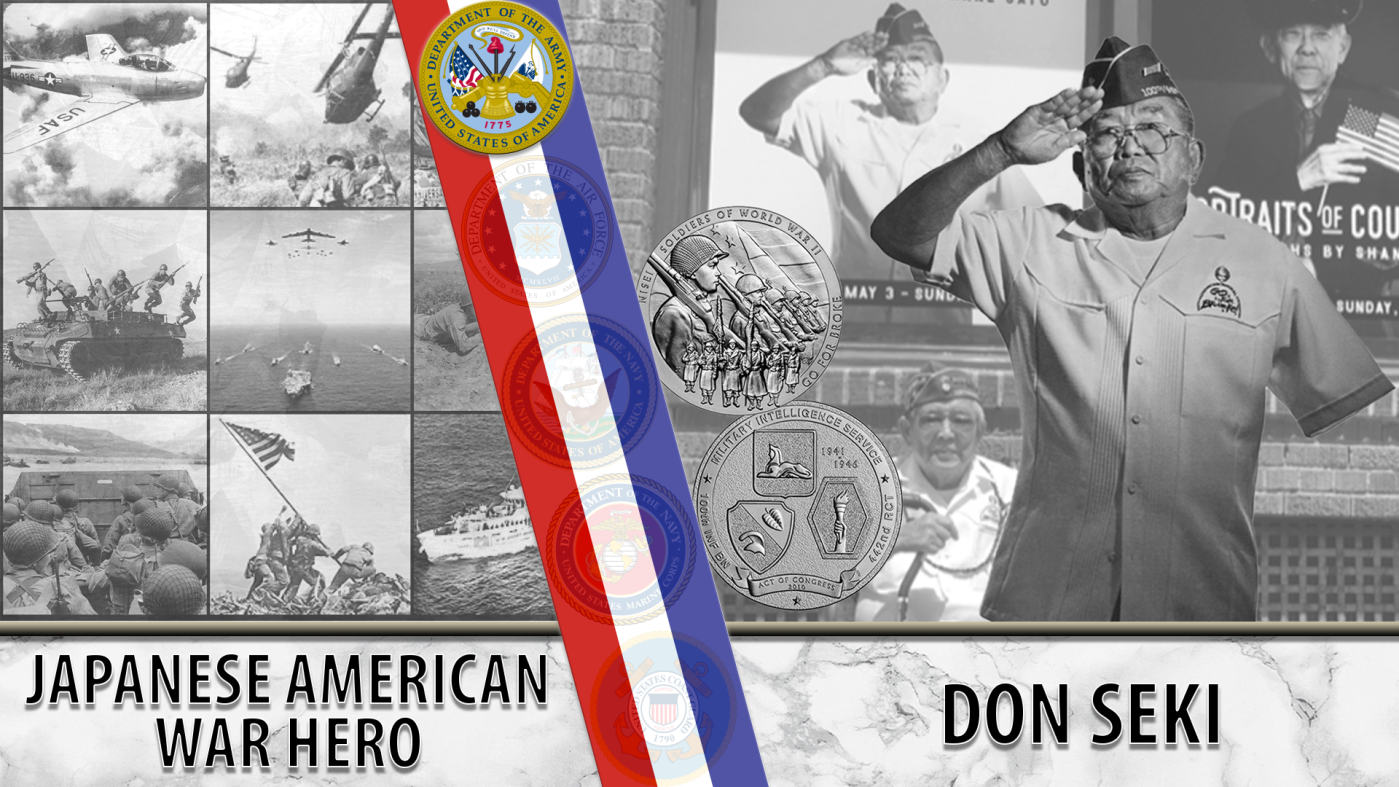

Don Seki served as a member of the 442nd Regiment, a unit of Japanese American soldiers, during World War II.

Born in December 1922, Noboru “Don” Seki grew up in the Manoa Valley in Honolulu, where his parents worked as farmers on a sugar plantation. He was the youngest son and grew up barefoot; his family was at the bottom of the plantation economy. At the time, two of every five Hawaiians were Japanese American, and discrimination against Japanese American citizens was not as prevalent as it was on the mainland.

When Seki was 17, his parents moved back to Japan. Seki, however, stayed behind. On Dec. 7, 1941, only three days after they said their goodbyes, the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred. Life as he knew it changed forever and Seki would not see his parents again until 1947.

After he graduated from high school, Seki began serving locally by digging trenches and building machine-gun nests. However, because he was Japanese American, many people viewed Seki as a member of the enemy. Japanese American leaders were sent to internment camps, while those who remained faced discrimination and heavy surveillance.

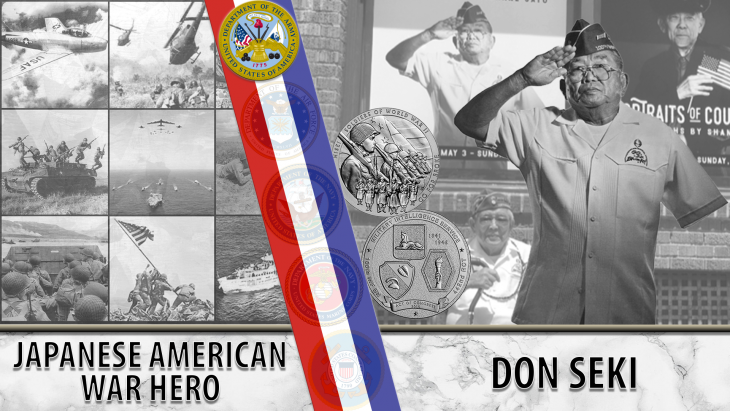

In March 1943, Seki volunteered for the 442nd Regiment, which was composed entirely of Nisei soldiers, American-born children of Japanese immigrants. The 442nd fought in five different campaigns in both Europe and the Mediterranean and was one of the most decorated units of its size in U.S. military history, receiving over 18,000 awards for their battalion of just over 14,000 men.

Seki completed basic training at Camp Shelby, just south of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. The only white people at the camp were the regiment’s officers. There were concerns about potential racial unrest among the neighboring civilians, so the military authorities tried to keep the Nisei soldiers out of the locals’ sight, especially upon their troop train arrivals.

The 442nd Regiment’s first combat experience was in Naples, Italy, where they joined the Rome-Arno campaign in fighting German forces. The 442nd then fought in the Battle of Bruyères, which was one of the costliest American battles in World War II.

In late 1944, while fighting in the Vosges Mountains in France, Seki’s company rescued the “Lost Battalion,” the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry “Alamo Regiment” from Texas. There were high casualties. Seki was seriously wounded by machine-gun fire after the rescue, resulting in him losing his left arm.

After his injury, Seki spent two years in rehabilitation and receiving prosthesis training. He returned home in 1946. For his service, Seki received the Purple Heart, the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, the Bronze Star, the Good Conduct Medal, the French National Legion of Honor and the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor.

After he retired from the military, Seki worked for 37 years as a comptroller at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard. He eventually retired to West Los Angeles.

Seki appears on the cover of Shane Sato’s book, “The Go for Broke Spirit: Portraits of Courage,” which features photos of military Veterans. He also made a cameo in the 2019 indie movie “American.”

On July 28, 2020, Seki passed away at the age of 96. He is survived by his wife, three children and two grandchildren.

We honor his service.

Writers: Katherine Berman and Aubrey Hutson

Editors: Elissa Tatum, Katie Wang

Researchers: Monique Quihuis, Richard Aguilera, Raphael Romea

Graphic Designer: Grace Yang

Topics in this story

More Stories

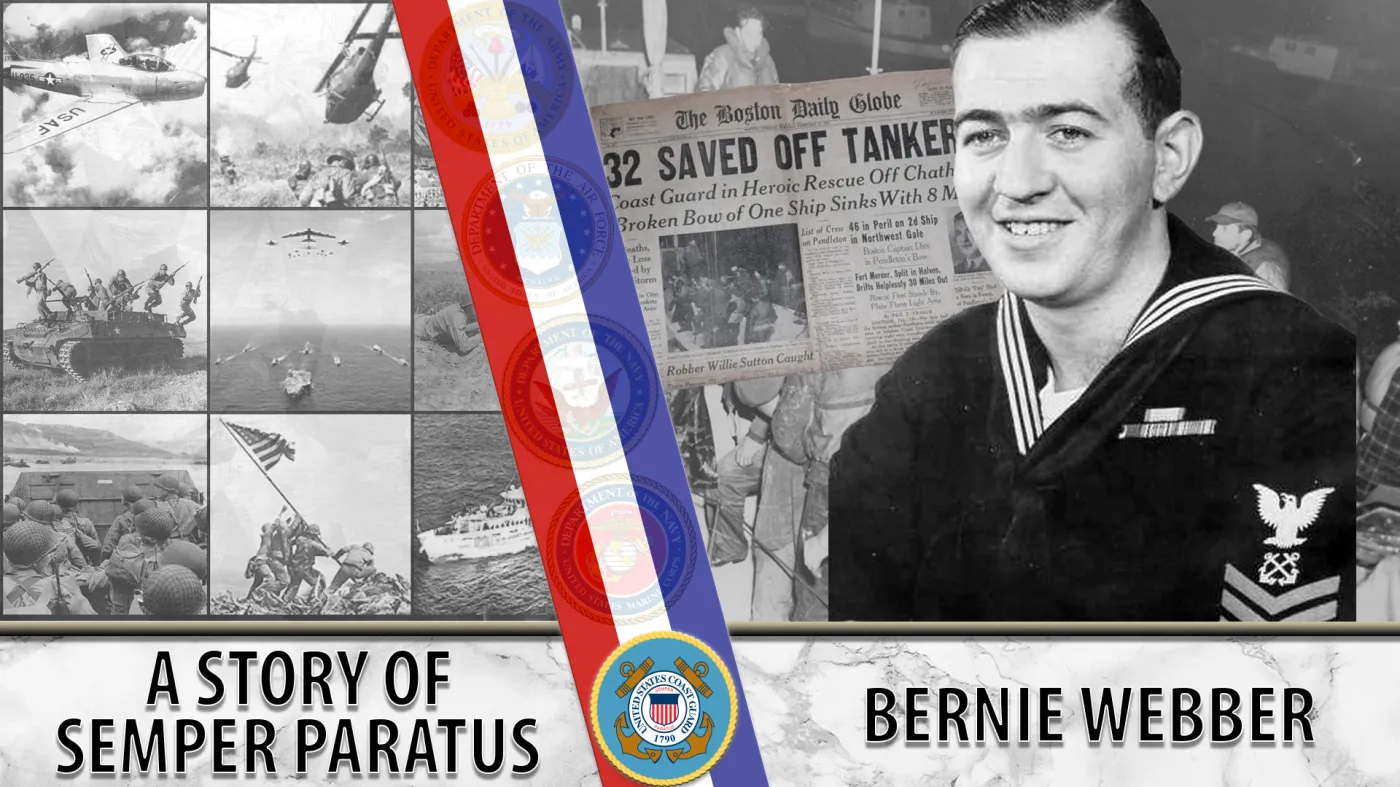

Bernie Webber led one of the greatest Coast Guard rescues in history that was later chronicled in the book and movie, “The Finest Hours.”

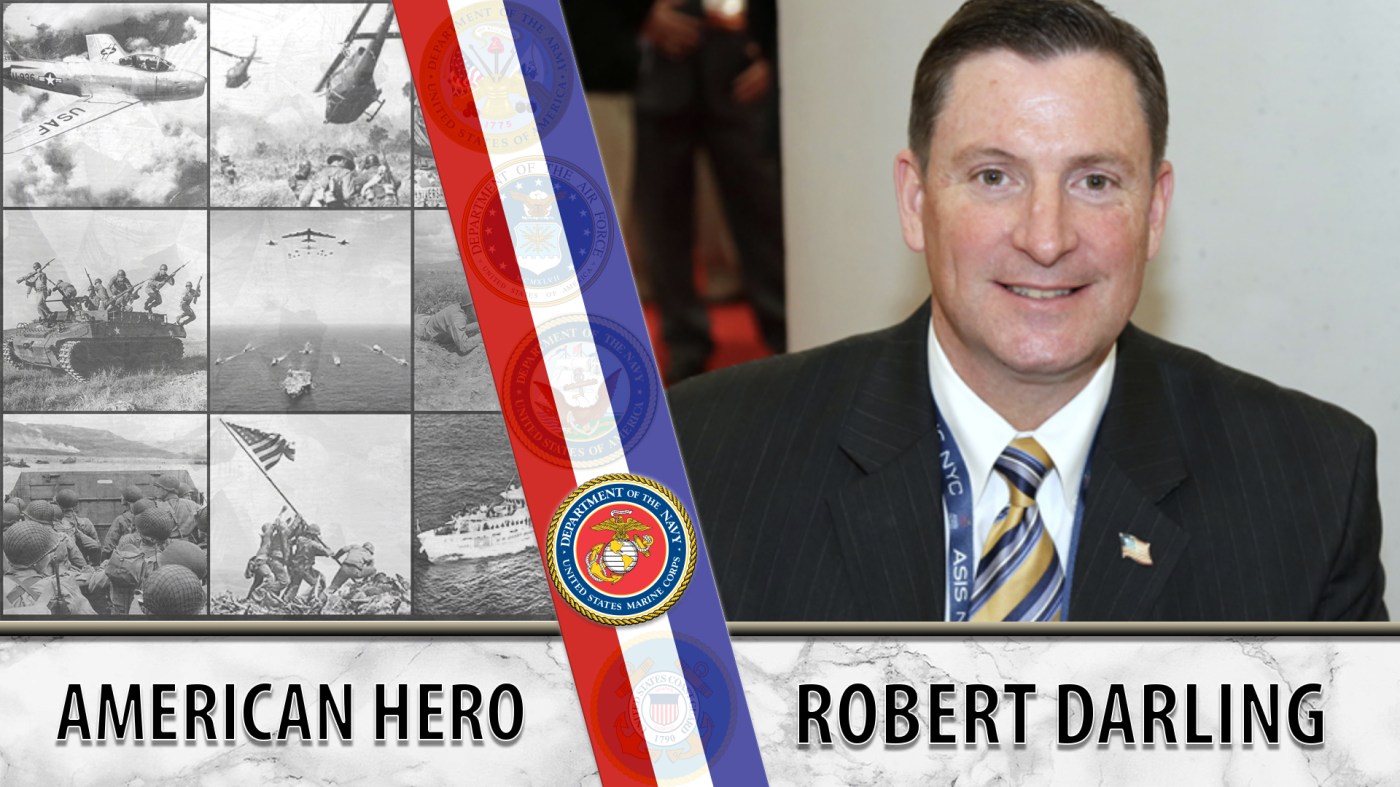

As the events of 9/11 unfolded, Marine Veteran Robert Darling served as a liaison between the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney in the underground bunker at the White House.

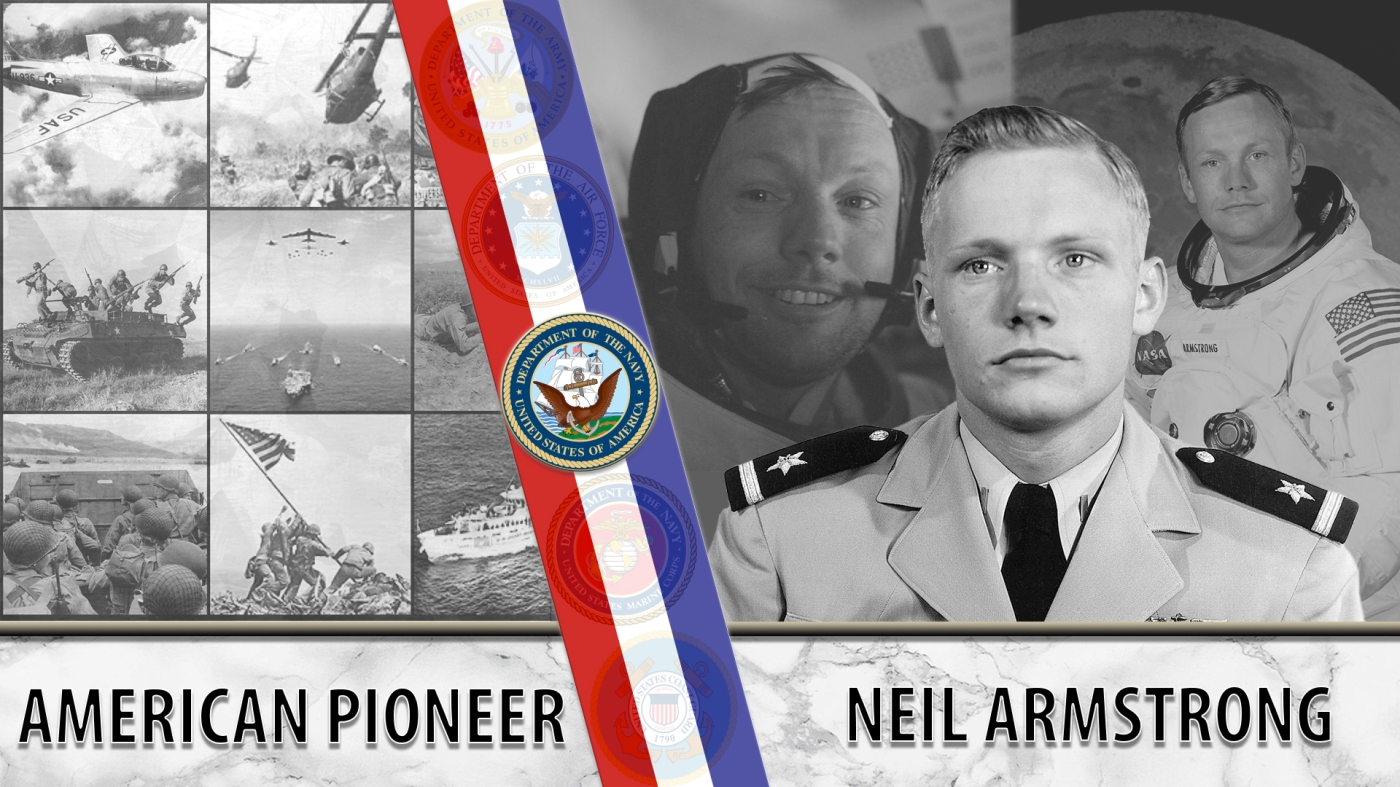

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon. He was also a seasoned Naval aviator.