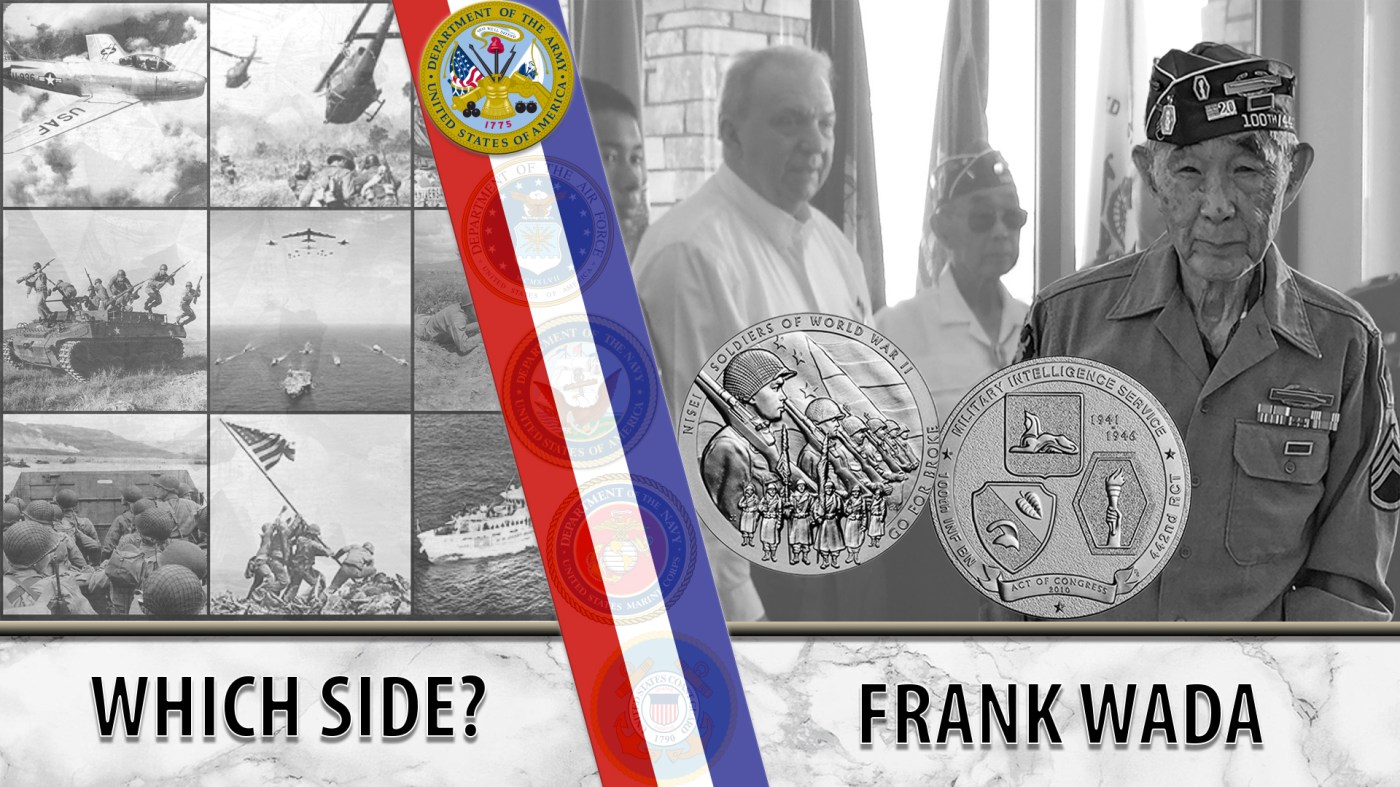

People doubted Frank Wada’s loyalties because he was Japanese-American. However, Wada readily volunteered to fight for his country when given the chance.

Born in Redlands, California, in 1921, Frank Wada faced racial discrimination throughout his childhood. He was only allowed to swim in the public pool on Mondays, which was the day that non-white children were granted entry. At the movie theater, he was expected to sit in the upper balcony. And, he was only one of the few Japanese American families in town, so he had difficulty finding a community he could closely identify with. No amount of education seemed to liberate Wada from discrimination. In his senior year of high school in 1938, a fellow student asked him, “Which side are you going to fight for?” Wada’s mother got wind of his harassment and told him that if he were to ever fight, it would be for America.

The discrimination Wada faced throughout his childhood reflected how the political tensions during the 1930s bled into his everyday life. From a domestic perspective, anti-Japanese sentiment was nothing new. Immigration to the U.S. from Asian countries had been continuously limited since the mid-1800s and culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924, which effectively restricted almost all immigration from Asia. On the international front, Japanese aggression in northeast China, despite U.S. denunciations, and the allegedly unintentional Japanese sinking of USS Panay in 1937, further fueled anti-Japanese sentiment in the 1930s.

After graduating high school at the age of 16, Wada moved to San Diego and worked at his sister’s ranch. There, he experienced much less racial discrimination and even felt comfortable attending local football games. On the day of Pearl Harbor, he was about to go to a football game when he heard of the attack on the radio. Frustrated with the news, Wada went to his local draft board hoping to enlist, but he was promptly rejected.

On Feb. 19, 1942, Wada learned about President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 from a lamppost notice. With no other option but to accept internment, Wada and his family packed their suitcases. They were placed onto several trains without being told where they were going and eventually arrived at a concentration camp in Poston, Arizona, in the middle of the Sonoran Desert.

Wada tried to make the best of his internment. He kept busy by carving wood, participating in community events and sneaking around after curfew to meet up with his girlfriend, Jean Ito. Even so, Wada had to endure unbearable levels of heat and a lack of privacy while living in primitive housing arrangements.

Nearly one year into his internment, Army recruiters visited Poston to recruit soldiers for the 442nd Regiment. Wada volunteered. Looking around at his family and friends, he figured that if nobody volunteered, they would never get out of the camp. Wada received backlash from fellow internees for deciding to volunteer. Many people feared that his service might somehow make things worse for the Japanese American community. Nonetheless, Wada persevered and moved ahead with volunteering, staying true to his mother’s expectation that he would fight for America.

Wada was sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where he met fellow Japanese Americans from all around the U.S. Wada and his peers trained for about one year. In 1944, the 442nd Regiment was sent to Europe to serve in the Rome-Arno campaign. Wada was ready to show to the world “which side” he would fight for.

Within Wada’s first months of combat in Italy, he demonstrated that he was a capable leader. He started off as a scout on the frontlines but quickly rose through the ranks. By the second week, he became acting squad leader and led his team through countless combat experiences. After a month, he was promoted to acting platoon sergeant.

Wada nearly lost his life in October 1944 during the battle to liberate Bruyères, France. While on a hill overlooking the French village, Wada briefly glimpsed a German tank shoot in his direction. The shot hit the trees above him, and shrapnel came raining down. Wada suffered shrapnel wounds to his lower body and was sent to a military hospital for the next three months before resuming command of his squad.

When the war ended in 1945, Wada returned to the U.S. He has continued to honor the country he fought for and its Veterans ever since. In 2013, at 92 years old, he and his family donated to the Miramar National Cemetery Support Foundation to help purchase new flags.

Wada was awarded a Congressional Gold Medal in 2011 and the French Legion of Honor in 2015.

Through a lifetime of service to the U.S., Wada has demonstrated clearly “which side” he fights for. To hear Wada recount his life experiences, listen to the Japanese American Military History Collective’s oral interviews conducted with him in 2004.

We honor his service.

Writers: Aubrey Hutson, Calvin Wong

Editors: Elissa Tatum, Katie Wang, Julia Pack

Researchers: Richard Aguilera, Raphael Romea, Ileana Rodrigues

Graphic Designer: Grace Yang

Topics in this story

More Stories

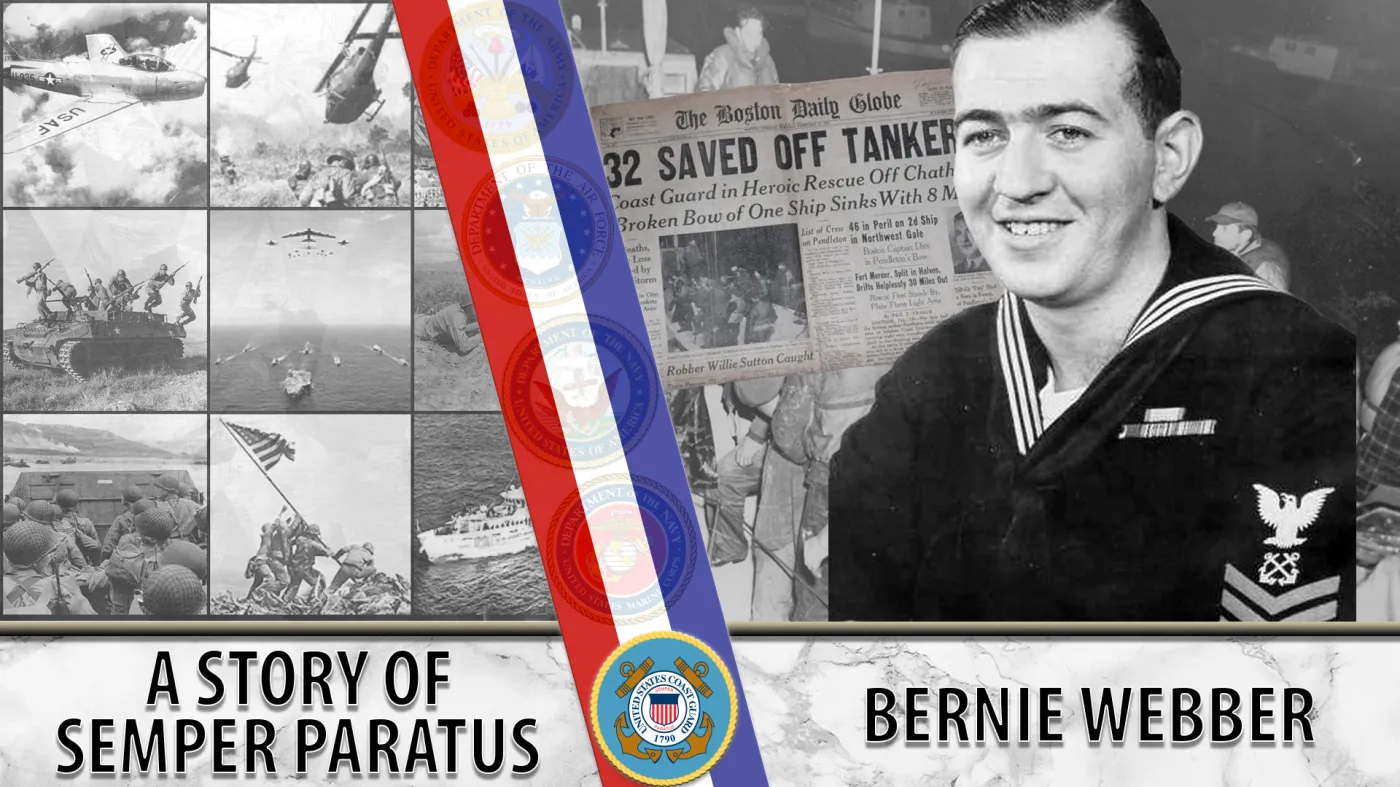

Bernie Webber led one of the greatest Coast Guard rescues in history that was later chronicled in the book and movie, “The Finest Hours.”

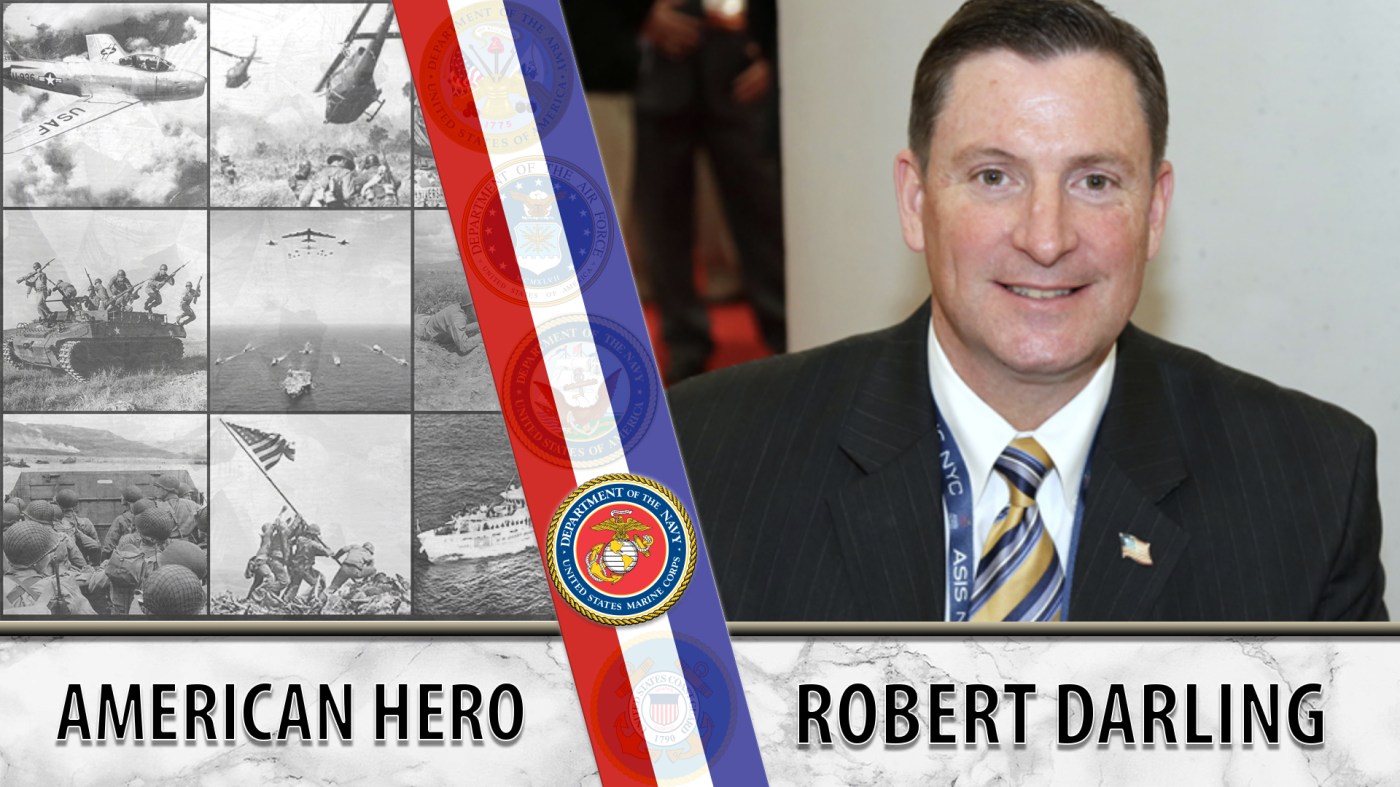

As the events of 9/11 unfolded, Marine Veteran Robert Darling served as a liaison between the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney in the underground bunker at the White House.

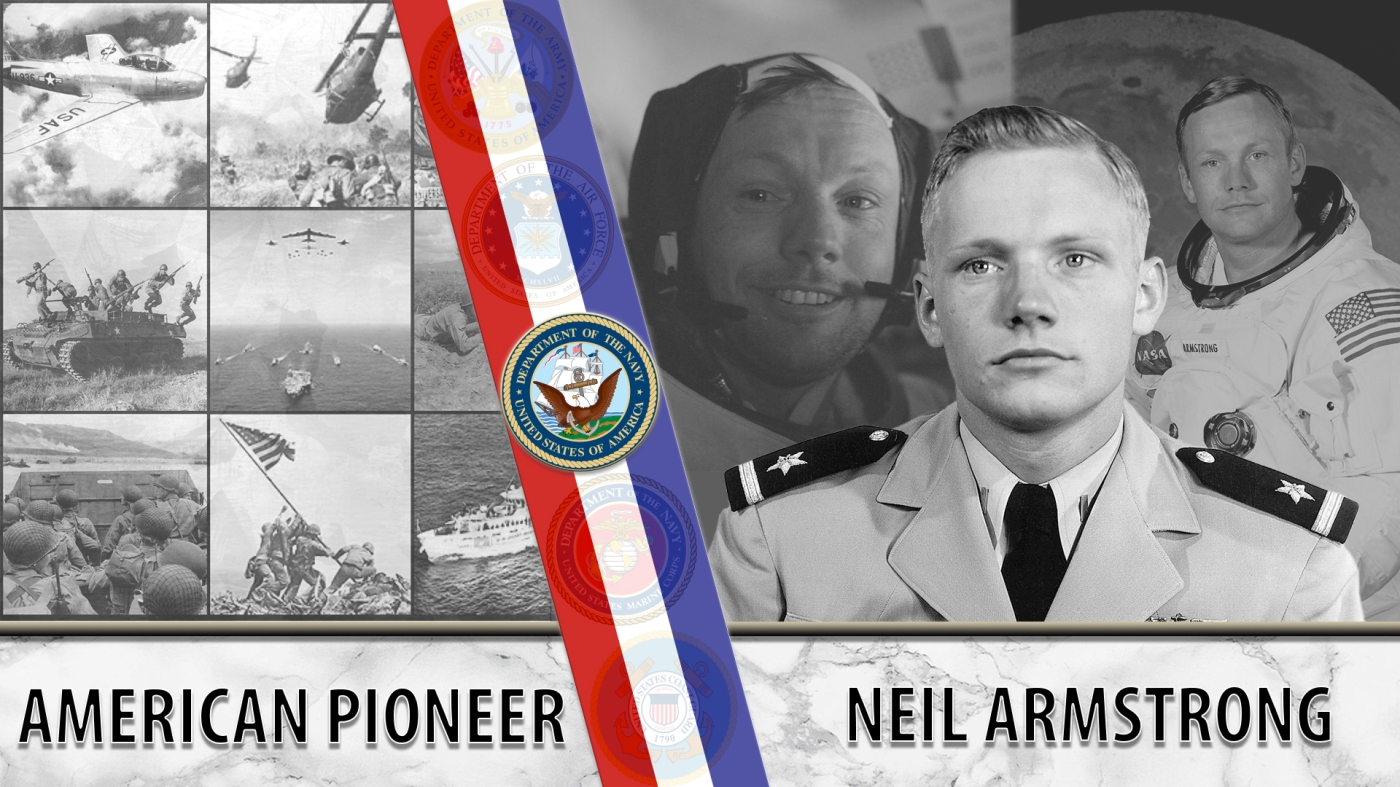

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong was the first person to walk on the moon. He was also a seasoned Naval aviator.